You know that the Peak was once off-limits to Chinese residents. But did you know that a large part of Cheung Chau was too?

The "Cheung Chau (Residence) Ordinance, 1919", passed on August 28th that year, stated "no person shall reside within that southern portion without the consent of the Governor-in-council."

Here's a map from 1938 [1], showing the European "southern portion" and the boundary that separated it from the Chinese north: Click to view map

1919 - A racial or economic division?

In 1919 when this law was proposed in the Legislative Council [2], the two Chinese members were firmly against it. Mr Ho Fook declared:

"In view of the fact that the war [World War I] has been won by all races in the Empire I cannot be party to the passing of the Bill which, in my opinion, is nothing less than racial legislation. I hope you will see your way to withdraw this Bill as suggested by my colleague."

The British expressed surprise, and stuck to the line that this law was intended to preserve the southern area as a place where British and American missionaries could live with their families. The missionaries needed a place to rest after spending time working in Southern China. They had previously used the Peak for that purpose, but it had become too expensive so they had turned to Cheung Chau. Now there was the risk that would also become too expensive, so they'd turned to the British government for protection.

The law gave the missionaries the protection they needed, and was "an entirely economic question and not a racial question at all."

The law was passed that same day, "Mr Lau Chu Pak and Mr Ho Fook voting against it."

c.1925 - A beach for the Europeans

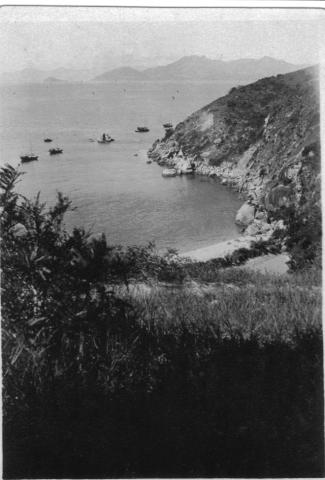

Sean sent us the following photo of Kwun Yam Beach (aka Afternoon Beach) on Cheung Chau, with notes:

Came across this picture among some family pictures. On the back is written "One corner of the beach only for Europeans on the other side is one for the Chinese".

The handwriting is my great aunt's and I would date the picture to the early to mid 1920s.

Kwun Yam beach was south of the boundary line. Just a few years after the law was passed, the division of the island was already clear.

1938 - Who lived there?

The 1938 map of Cheung Chau shown at http://gwulo.com/map-of-places#15/22.2054/114.0286/Map_by_ESRI-1938_Che… has a list of the 36 houses in the European area:

| 1. | 16. Mr J A Kempf |

| 2. Mr E C Mitchell | 17. Mr N G Wright |

| 3. Mr Johnston | 17A. Mr N G Rodine |

| 3A. | 18. Mr G F Sauer |

| 4. | 18A. Dr Cleft (believed to be a typo for Dr Clift, see comments below). |

| 5. T W Pearse (London Mission) | 19. Mr W W Cadbury |

| 6. Mr P N Anderson | 20. Mr Smith |

| 7. Mr I. J. Lossius | 21. Mrs L. Franklin |

| 7A. | 22. Mr R A Jaffray |

| 8. Mr C A Hayes | 23. Mr C G Alabaster |

| 9. N Z Pres Mission | 24. Mr M R Vickers |

| 10. Treas. N Z Presbtn Mission | 25. Mr J M Dickson |

| 11. Mr Rev. L J Lowe | 26. Mr C M Dos Remedios |

| 12. Mr Smyth | 27. Mr T H Rousseau |

| 12A. Mr Sonvea | 27A. Mr Kastmann |

| 13. Mr A H Mackenzie | 28. Mr P Hinkey |

| 14. Mr J C Mitchell | 29. Mr A J Brown |

| 15. Mr J J Lossius | 30. Mr Smith |

Despite the British comments in 1919, the law had had a clear racial effect - there are no Chinese names on the list.

Then how about the stated goal to create an area for missionaries to live? In 1938 were the European houses owned by:

- church / missionary organisations,

- landlords renting them out as a business, or

- private owners who wanted a holiday home away from the city?

Though the list doesn't say if it shows residents or owners, I believe they're owners as the same name appears next to more than one house. Then only four houses, 5, 9, 10 and 11, list owners with a clear church / missionary connection.

Among the other names I only recognise Mr Lossius [3], owner of houses 7 and 15. We've seen a letter from him published in 1907 [4], where he proclaims the benefits of "Christian Science", so he may have been listed as owner on their behalf.

Does anyone recognise any of the other names, and can say whether they suggest private or church ownership?

1946 - The law is repealed

In July 1946, Bills were introduced to repeal both laws that restricted residence on the Peak and in south Cheung Chau [5]. In both cases the Attorney General noted that "it would be out of harmony with the spirit of the times to retain the Ordinance".

Ho Fook had tried a similar approach in 1919, but it took WW2 to bring the British side around to his line of argument!

Later that month the Bills were passed, and the laws repealed.

1950s - Did anyone tell Cheung Chau the law had been repealed?

Apparently not:

When I was a girl I lived on Cheung Chau from 1950 to 1954 [...]. Being an American I lived in a house on the southern hill just past the Bible School. For most of the time I lived there only one other family lived fulltime on the hills so five of us kids had the full run of the island above the village. The Kwun Yan beach (called Afternoon Beach by the English) was restricted to Europeans and strictly enforced. Tung Wan Beach (called the Chinese Beach) was the only one the village people could use and swimming and sunbathing were not a popular past time for the native people so didn't get a lot of use. [6]

Does anyone know who it was that "strictly enforced" the access to the beach? And when did the segregation finally stop?

2012 - What remains?

The boundary: Although the boundary no longer has any legal meaning, several of its granite markers are still standing. Here's a photo of the northern stone, marked BS1 on the 1938 map, but painted as "B.S. No. 14" today. A building has grown up around it, but it is still in its original location:

A church presence: Modern maps shows many church sites in south Cheung Chau: Caritas Ming Fai Camp, Salesian Retreat House, Shun Yee Lutheran Village, etc. How many can trace the ownership of their site back to the pre-WW2 days?

The 1938 buildings: Are there any of the buildings from the 1938 map still standing? The "I lived on Cheung Chau from 1950 to 1954" writer suggests not:

The trees had all been cut down by the Japanese during the occupation of WWII so the island was quite barren back then. They also knocked down many of the houses on the hills to get the rebar out and when I lived there the remaing walls and rubble made great "play grounds". [6]

The European beach: Last year I was lucky to visit Cheung Chau with Don Ady and Laura Darnell. Their fathers were American missionaries, and Don and Laura had lived on Cheung Chau shortly before the Japanese invasion in 1941.

During our visit we had a very kind local gentleman join us to show us around. He took us over to Kwun Yam beach, and commented:

"This beach seems more popular with the Westerners than the Chinese. I don't know why that is."

Maybe the effects of that 1919 law still haven't completely faded away.

If you have any comments / questions / corrections, or you can add any memories of Cheung Chau, please let us know in the comments below.

Regards, David

References:

- The 1938 map is available in the Hong Kong Public Records Office, ref: MM-0094. Here it is shown overlaying a present-day satellite view of the island. Red markers represent Places that have a page on Gwulo. Orange markers represent the numbered houses that are shown on the paper map. You can read instructions on how to get the most from the map here.

- See the minutes of the Hong Kong legislative council for 28th August, 1919.

- Jacob Johan LOSSIUS (aka Iacob) [1853-1942]

- Comment to [3]

- The Bills to repeal the two ordinances were first read on 19th July, 1946 (see minutes). They were read a second & third time, and passed into law on 25th July, 1946 (see minutes).

- Comments on the Hong Kong Outdoors website.

Comments

Map of Cheung Chau Boundary Stones

Reference can be made to this link: https://www.historicalwalkhk.com/mmp/fullscreen/11/?marker=297 regarding the position of the Cheung Chau Boundary Stones and the former European Reservation Area south of the orange line.

Cheung Chau Missionaries 1938

[Updated 3/12/25]

Just 13 (in bold), though Rev Lowe, House 11, may have been one. I don't hold out much hope for 2 Smiths and a Brown. Edit: One Smith down and one to go! Amazing sleuthing by moddsey!

2. Mr E C Mitchell

3. Mr Johnston

5. T W Pearse (London Mission)

6. Mr P N Anderson

7. Mr I. J. Lossius

8. Mr C A Hayes

9 NZ Mission

10 NZ Mission

11. Mr Rev. L J Lowe

12. Mr Smyth

12A. Mr Sonvea

13. Mr A H Mackenzie

14. Mr J C Mitchell

15. Mr J. J. Lossius

16. Mr J A Kempf

17. Mr N G Wright

17A. Mr N G Rodine

18. Mr G F Sauer

18A. Dr Cleft

19. Mr W W Cadbury

20. Mr Smith

21. Mrs L Franklin

22. Mr R A Jaffray

23. Mr C G Alabaster

24. Mr M R Vickers

25. Mr J M Dickson

26. Mr C M Dos Remedios

27. Mr T H Rousseau

27A. Mr Kastmann

28. Mr P Hinkey

29. Mr A J Brown

30. Mr Smith

Missionaries/others with property on Cheung Chau but not known about / where -

Merrill Steele Ady 1940s - Presbyterian Church

Darnell 1940s

Sauer House #18

Decker House #25 1950s

John Livingstone McPherson

European Reservation

My family moved to Cheung Chau around the early 1950s. There was already quite a large population of local islander families all over the area that used to be the European Reservation, so the European foreigners were just a tiny minority. So most of us understand that they are just like friends or guests and that most of them will leave the CC island sooner or later for good.

To us, nobody would care about the existence of any boundary stone. I suggest that the ER establishment in past history must be nothing about racial issues.

My understanding goes directly to the reality of the hygienic condition of CC. That was very underdeveloped in those days. All water supply was from local wells, which could be compromised by dirty rain water or even sewage Drainages. Tap water was not there prior to ,say, 1950.

Many European houses had to have their own wells or one from a nearby farmer's.

The co-existence was very respectful and peaceful. So that's the way I know it.

Tung

1935 Travelling by Sedan Chair on Cheung Chau

Seen on Facebook. Getting around Cheung Chau: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1639311162816368/posts/24051679804486184/

1935 Travelling by Sedan Chair on Cheung Chau

The location seems to be at the foot of Ming Fai Road in the Fa Peng area.

As of today, there is a very different scenario apart from the 1937's on the same location. First is the new alignment of the paths and the improvement of the water system, integrating the creek and the other water catchments in this area. The farmers' fields have gone for a long time ago, and the landscaping is only directed by the benefits of tourism.

Here are the locations of interest as labeled: 22.206267, 114.034902

22.2057846, 114.0346238

22.2058012, 114.0346337

22.2058402, 114.0346415

I saved a Google Street View for my own viewing, as follows:

https//maps.app.goo.gl/DxVX8nu9hFnGAA.htm

With the 1935 photo, I think this street view will help us to figure out the original pathway, with the slow flowing creek water running below the footbridge. The water collected in the pond which is just next to the temple is so clear and clean, and is the best creek of pure spring water on the CC island I know. Maybe it has a traceable amount of sulfur in the water, keeping the area free of snakes. (Any ideas? )

More information from the original 1935 photo :

There is a small creek running under this part of the road. A pond nearby, which is not within the photo, provides fresh water for the farmer's needs. Further downstream there stood a small temple or a shrine. It would be just less than half a minute's walk away from Koon Yam Wan.

The people in the photo seemed to be just crossing the footbridge and going uphill at the foot of Ming Fai Road, I suppose.

They were quite likely coming from Peak Road, which is quite level at an elevation of about one hundred feet, and then took a turn eastward after passing the Assembly Hall area. This latter path leading to a valley is known to be too steep, quite a risk to most walkers. Then, at all the junctions, they would continue but skip all the off roads to Koon Yum Wan, Fa Peng Road or the Nam Tam Wan area.

Walking uphill on the Ming Fai Road, which means turning to the right after crossing the footbridge, is definitely tough and challenging for those with physical weaknesses. Nevertheless, the high end of this road has the best sights overlooking most of the CC island, and its surrounding landscape, plus all the waters around.

The terrace of farmers' fields remained to be on the left side of the footbridge.

BTW, a rectangular stone wall near the old footbridge was part of the boundary of the sports field of the English College I once attended in the early 1960s. So to me, this location has been a familiar spot for a few years. My earliest memory of the same sport would be from the mid 1950s. That was quite appeared the same as the 1935 photo. As a kid, mom took me along as she came to this area to buy some second-handed furniture from a European house. And much later, before my departure for overseas, I purposely visited the source of this creek. It is a spring! It was so hidden from the passing traffic.

Tung

1935 Travelling by Sedan Chair on Cheung Chau

The area was once called

Good Luck Farm or Lucky Farm. In Cantonese, is better be known as 好彩農塲.

Any other feedback?

Tung

Missionaries impact back in the USA

Moddsey posted this obituary of Anne Lockwood in the European House 14 thread: https://medium.com/@ClimateBoomer/the-remarkable-life-of-anne-lockwood-romasco-1933-2017-9fd507564507

At the end of this was an eye-opening observation of the radical and unexpected impact American missionaries had back home!

'Also in the last year of Anne’s life, American intellectual historian David Hollinger published Protestants Abroad: How Missionaries Tried to Change the World But Changed America. The summary states that experience abroad “made many of these missionaries and their children critical of racism, imperialism, and religious orthodoxy. When they returned home, they brought new liberal values back to their own society [and] left an enduring mark on American public life as writers, diplomats, academics, church officials, publishers, foundation executives, and social activists.”

Anne is cited in the footnotes. She would have loved the book.'

- - - - - - - - - -

Missionary Winifred Lechmere Clift wrote these insightful words about the effect of these missionaries in China: ‘Science will never know how much she owes the opening door in China to the steady, plodding teaching of Christianity by thousands of obscure missionaries.’

Obscure maybe, but they changed their world!

Names of House Residents on Cheung Chau

Person Pages have been created for Edward Harold Smyth and Mrs. Lily Franklin, residents of Houses No. 12 and 21 respectively.

Hong Kong Heritage Project and European House #1

The Hong Kong Heritage Project has a nice collection of photographs of Cheung Chau from the 1930s. Scenes of European bungalows and a house called "Sunnyside" are listed below.

Note: Any form of publication of the photographs must be approved by HKHP. Please get in touch at enquiry@hongkongheritage.org for making relevant applications.

Cheung Chau collection: https://www.hongkongheritage.org/nodes/search?datefrom=&dateto=&keywords=cheung%20chau&orderby=node_title&order=asc&ntids=WyIxIiwiMiIsIjMiLCI0IiwiNSIsIjYiLCI3IiwiOCIsIjkiLCIxMCIsIjExIiwiMTIiLCIxMyIsIjE0IiwiMTUiLCIxNiIsIjE3IiwiMTkiLCIyMCIsIjIxIiwiMjIiLCIyMyIsIjI0Il0=&filter=eyJudGlkcyI6W10sImZhY2V0Ijp7fX0=&a2z=W10=&page=1&viewtype=list&type=all&digital=0&in=0&access=0&has=W10=&bid=0&meta=W10=&metainc=W10=&inmetas=

European bungalows: (1)

House "Sunnyside": (1) and (2) and (3). Perhaps related (4) and (5)

In the 1930s, L. G. G. Westcott and his wife were residents of No. 1 Bungalow, "Sunnyside", Cheung Chau.

Their bungalow, "Sunnyside" was available for rental as a vacation house as well as a holiday camp for army personnel. In 1939, men of the 1st Bn, the Middlesex Regiment and 2nd Bn, The Royal Scots were in residence together at "Sunnyside". Photograph in the Hong Kong Telegraph 19 August 1939.

No 1 House

Is this an amazing find, moddsey! So this is actually House Number 1, on which we have had no info so far, and it's not marked on the 1938 map. Do we have any inkling where it might have been? Logically it should be near to #2.

Looking at the photos, photo 2 with the porthole window above the front door looks like House #5.

In Photo 3 are we looking from somewhere in the region of House #5 north west towards Pak Kok Tsui?

Do we make a place page for House #1?

Re: No. 1 House

The porthole window is interesting. If you can, please create an interim place for House No. 1 as I am unsure where it is within the European reservation. From the local press, the house was still in use up to 1940 and referred to as a holiday camp.

I think the panoramic view of the other European bungalows may have been taken from "Sunnyside"?

Both L. G. Westcott and his wife were interned at Stanley Camp. I assume they resided at "Sunnyside" prior to the Japanese occupation.

For reference, the name "Sunnyside" is mentioned in the newspapers from 1935 onwards. House No. 1 and its connection to the Westcotts first appear in the Hong Kong Daily Press 21 September 1934 (see here) when Westcotts' son, Frank (L. F. G. Westcott) had missed the last sailing of the Cheung Chau ferry.

No. I House

My understanding of the No. 1 House on Cheung Chau island in the 1950s, is located on the highest terrace by the junction of the Peak Road and the top end of the School Road.

It was quite well-known to the Cheung Chau folk as Address # 888, which is clearly written on the 1938 map of CC Land with European Reservation Houses Numbers appearance.

The name of the villa is Tat Yuen. As of the 1950s, the homeowner was a local business owner. It also housed multiple families as renters. We knew it had to be comfortable for living there.

Many of the early houses on the 1938 map were labeled with the three-digit number system. It seems to be worthwhile to keep this "888" number. That has a very good meaning, doesn't it?

Tung

No 1 House

Thank you for that wealth of information, moddsey.

Is an interim page the same as a place page?

The panoramic view of the houses (1) must have been taken from a place to the north of House 30. You can take a line straight through House 27 to House 5.

I like Tung's suggestion of the high point at junction of Peak Road and School Road. Would this accommodate this view (3)? Tung do you have a reason for that choice?

In pic 3, are we looking over Tung Wan to Tung Wang Tsai with Hei Ling Chau in the distance?

No. I House

The view (3) is consistent with from #888 or No. 1 as suggested.

Some trees still remain today!

The view is directed to the northwest by the photo's right margin. If we could remove all the trees, we would see lots of fishermen's boats in this main harbor, the Chung Wan and the Adamasta Channel waterway along the coastline of the Chi Ma Wan peninsula of Lautau island. The left margin of the photo is directed towards the southwestern view.

The view (1) is also valid as stated, it is northeast of House No. 30.

It looks like House No. 1 has been transformed to be the later "Sunnyside ". The latter seemed to be occupied by more than just #888. Together with #887 and #889, they formed a larger building block of property. And #890, #891, and #892 were the adjacent building blocks, so the site was able to be a resort for many guests or vacationers.

Tung

Place for House No.1

Yes, an interim location is the same as a place page.

To accommodate a large number of army personnel at "Sunnyside", the grounds would have been rather extensive. See photo here in the Hong Kong Telegraph 19 August 1939.

No. I House

Wow!

Something new to me!

Tung

"Sunnyside", House No. 1 very likely on C.C.I.L. 30

A good find from hkspace-wl regarding Westcott posted on 24 November 2025.

There was some small claims case re his 'Army Holiday Camp' (No. 1 Bungalow) reported on the China Mail on Feb. 1939.

In the Government Records Office (link), it keeps a file with this entry description :

"SUNNING SIDE"[^] CHEUNG CHAU I.L. NO. 30, ON CHEUNG CHAU ISLAND, N.T. - APPLICATION FROM MR. L.G. WESTCOTT FOR COMPENSATION FOR - RUINED DURING THE WAR

CCIL 30 is on south west of CCIL 45 (cf here). So this bungalow is likely in the proximity of the Assembly Hall in the 1930s era. On the 1938 map, we could see the number "30" near its location.

In Aug. 1939, some news mentioned concerts in the hall and No. 1 "Sunnyside" together, for activity along the social line .

[^] sic (likely, typo of Sunnyside)

No. I House

Some random memories from my childhood days seem to be making it very interesting now, because I am feeling comfortable as well as fortunate enough to encounter an important part of the modern history of Cheung Chau, its reputation is far beyond just a humble fisherman's island.

2. Leaders of CC islanders are quite strong and united to work for the welfare of both the locals and their foreign counterparts. Respect each other and non-interfering are the key factors.

3. CC seems to be a part of the world village.

Tung

First government land in Cheung Chau auctioned 1907

The first government-owned land in Cheung Chau was auctioned in 1907.

After the land survey in the New Territories was completed and the land ownership disputes were clarified, the colonial government began to publicly auction the first government land in Cheung Chau.

In December 1906, Land Commissioner G.H. Wakeman announced that Lots 622, 623, and 624 in Cheung Chau would be auctioned at 2:30 p.m. on January 4, 1907, at the Hong Kong Lands Department office building.

Each lot is 735 square feet, and the owner is not entitled to access to the sea, and will not receive compensation if the government reclaims land in front of the lot.

Source: Cheung Chau Magazine.com

European House 17A

Viewing the 1938 list of occupants/owners, it is likely that House 17A was occupied by Rev. Hugo Gustaf Rodine of the American-Swedish Mission (aka Swedish Evangelical Free Church of the United States of North America or Scandinavian Evangelical Free Mission) based in Canton.

Born 16 February 1892, Polk, Nebraska, USA. Died 31 December 1971 in Los Angeles, California, USA.

He married Ruby May Nordin in 1915 and came out to China in 1917. See European House #17A

Ruined house(s) Cheung Chau

Just come across this video on You Tube. Ruined house(s) from 6.15.

Is it near Kwun Yam Wan?

Ruined House(s) in Cheung Chau

To Aldi,

I think :

Those ruined houses seem to be European House # 9 and # 10, off the steep hillside by the eastern shore of the Fa Peng Pennisula, not quite near the Kwun Yum Wan.

Tung