A few weeks ago we looked at how the 1920 map of Kowloon was added to Gwulo. Today we'll take a closer look at the map itself, and see what stories it has to tell of early 20th-century Kowloon.

Tsim Sha Tsui (TST)

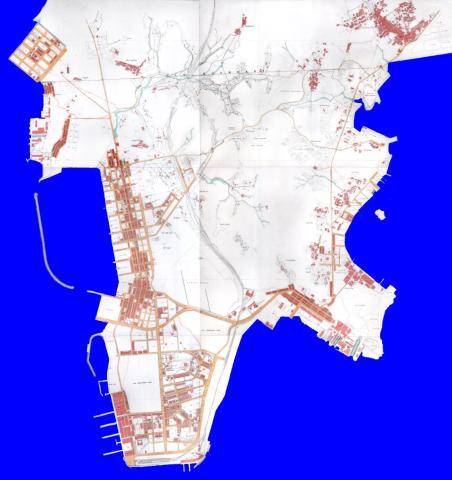

The start of the 20th century saw huge changes in TST. Here's how it had looked in 1896.

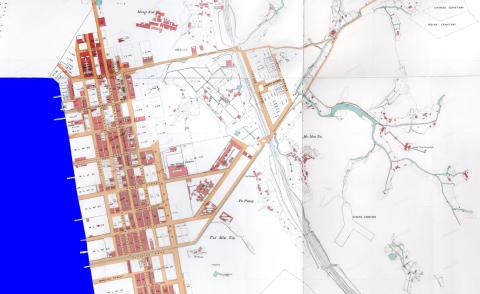

Most of the buildings in TST were concentrated in the strip of land along along its west coast, part of the Kowloon Wharves. We can see that roads had been marked out in eastern TST, but there weren't many buildings yet. (You might also spot some road names you wouldn't expect to see: Robinson Road, Chater Road, etc. The roads were renamed in 1909 to the names we know today).

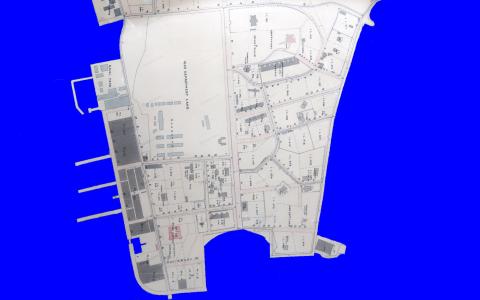

See how things had changed by 1920.

It shows even more roads on the east of the peninsula, and that the builders had been busy putting up new houses.

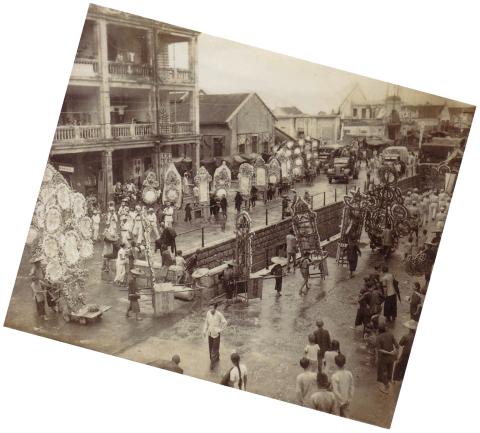

If you zoom in to the map you'll see that many of the new houses were detached or semi-detached, and that most had open space around them for gardens. Here's what life in leafy TST looked like at the time.

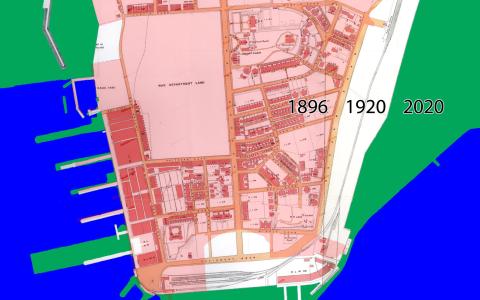

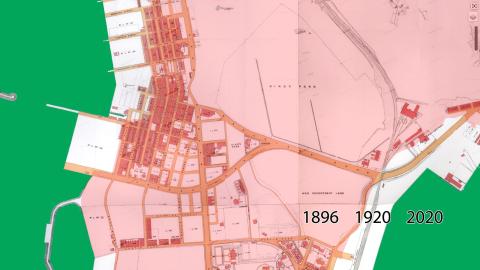

Reclamation is usually part of the story of Hong Kong's development, and TST was no exception. The area shaded pink below shows the extent of TST in 1896. The white patches show the additional reclamation to 1920, mainly around the south and east shores. Today's shoreline is shown in green - the south-west shoreline hasn't changed much in the last 100 years, but there have been major reclamations on both sides of northern TST.

Yau Ma Tei

In 1896, Nathan Road (then still called Robinson Road) would take you north through the heart of TST ... until it came to an abrupt end just after Austin Road. Most of the land immediately north of Austin Road was used for rifle ranges, so visitors weren't welcome.

Instead you'd have to turn left onto Austin Road and head west to the coast, then travel north until you reached the next built-up area. You'd arrived at the main district in early Kowloon, Yau Ma Tei. Looking at the map of Yau Ma Tei below, you'll see there is very little empty space around these buildings. Yau Ma Tei's residents lived in densely-packed terraced housing, very different from the TST homes shown above.

By 1920, the rifle ranges had closed, allowing Nathan Road to be extended north, and the new Gascoigne and Jordan Roads to be built.

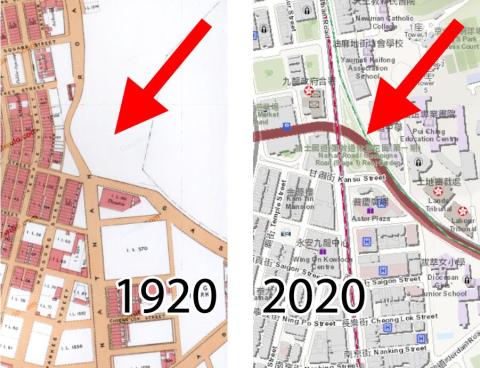

I've enlarged part of this map below, showing Nathan Road running down the map, Jordan Road across the bottom, and part of Gascoigne Road on the right. You might have noticed that Nathan Road doesn't run straight - there's a bend in the road at a point where it narrows. We'll come back to that later.

Follow Jordan Road, heading inland from the coast. When you reach the third block of land you'll see it has a circular shape in the bottom right corner. The map has it marked as Gas Works. You'll find the gas works shown on the 1896 map too, so it was one of the early pieces of infrastructure in Kowloon.

Continuing east along Jordan Road, you'll cross Nathan Road and eventually reach the junction with Gascoigne Road. The map shows there is a monument on the triangular junction. It was unveiled in 1908, commemorating the French sailors who died in Hong Kong in the 1906 typhoon.

Behind the monument is the Diocesan Girls' School (DGS). It would later expand west onto the adjacent plot of land marked "King's Park".

Turn left onto Gascoigne Road and at the end where it meets Nathan Road, you'll find another sign of Kowloon's growth, Kowloon's first theatre. This neighbourhood would become a centre for theatres and cinemas, with four generations of cinema on this site, the Alhambra Theatre across on the opposite side of Nathan Road, and the Majestic Theatre one block south.

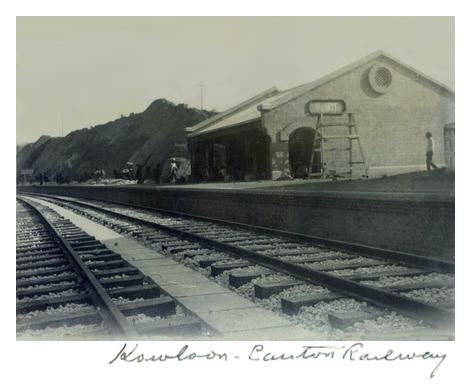

Make an about-turn and walk to the eastern end of Gascoigne Road, where you'll see two more major changes since 1896. Take a few steps forward into Chatham Road and you're standing on a bridge that crosses the tracks of the new railway to Canton. Look south and you'll see the Hung Hom railway station.

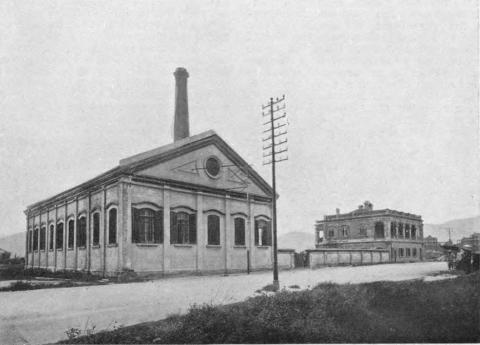

Then look ahead, and a little further along Chatham Road there's a large chimney. It belongs to Kowloon's first power station, producing electricity for Kowloon's growing population.

The 1920 map shows reclamation here too, that had formed new land along most of the 1896 shoreline. By 2020 this whole area has been reclaimed, with not a drop of sea to be seen.

Ho Mun Tin

It's not obvious what to call this section. A modern map of the area shows the Mong Kok and Yau Ma Tei MTR stations, and we'd think of it as on the boundary of those two districts. But on the old map, Yau Ma Tei is out of sight to the south, and Mong Kok is just visible at the very top. The name nearest the centre of the old maps is Ho Mun Tin - so that's what I'll go with.

Although we've seen that TST and Yau Ma Tei were both expanding rapidly, this part of Kowloon saw the greatest changes between 1896 and 1920. Here's the 1896 view, showing a very rural area, with streams, local paths, and a few village houses.

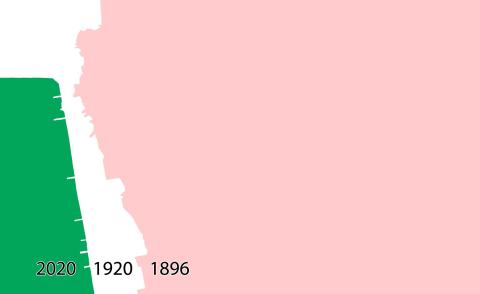

There were lots of changes by 1920. First look at the 1896 shoreline (pink), which still followed the shape of the natural coast. The 1920 shoreline (white) shows a straight seawall has been built and land reclaimed.

Filling in the 1920 map's details, we see that the strip of land near the coastline has been laid out in a grid of roads, and many of the new blocks of land are already built on. Nathan Road has been extended about half way up this section, with the outline of its further extension already shown. (In 1920 this northern part of the road was called Coronation Road. In 1926 that name was dropped, and the whole road became known as Nathan Road.)

Development is also heading inland, in the shape of a triangle bounded by Coronation / Nathan Road on the left, Argyle Street across the top, and Waterloo Road on the right.

In 1920, Argyle Street and Waterloo Road were only built to half their final width along most of their length. Probably to save money until there was enough traffic to need the full width?

The buildings to the left of Coronation / Nathan Road are the same tightly packed housing we saw around Yau Ma Tei. But across to the right of the road are three much larger plots of land, home to the Orient Tobacco factory, the Steam Laundry, and the Kwong Wa Hospital.

The plots of land where Argyle Street and Waterloo Road meet are also different. The three new roads there were named Peace, Liberty, and Victory Avenues, reflecting the recent end of the First World War. The lots of land along those roads are laid out for individual houses with gardens, so the new buildings there will be closer in style to the buildings we saw in TST.

Mong Kok

North again. We've run off the top of the 1896 map, so we'll go straight to 1920.

Mong Kok is shown on the map, as the name of a village. Near the village is a railway station, but it was called "Yaumati Station" - further evidence of which was Kowloon's main district at the time.

Another village with a familiar name is shown at the top of this section, Kau Lung Tong, written Kowloon Tong today. The project to build the Kowloon Tong Garden City Estate started in 1921, just a year after this 1920 map was drawn. Though the estate took its name from the old village, it's actually in quite a different location, away to the north-east and on the other side of the railway line.

A mystery solved

Before we move on to the last section, here's a little mystery this map has solved for me: From north to south, there are four roads that have to pass under railway bridges: Waterloo Road, Argyle Street, Prince Edward Road, and Boundary Street. The first three pass under their bridges in a straight line, so why do drivers on Boundary Street have to navigate a curve in the road?

When the railway was built, there was no Boundary Street. The boundary - what used to be the boundary between British Kowloon and China - was just a line on the map. When Boundary Street was built some years later, the engineers faced the problem of how to get the new road through the railway embankment.

The 1920 map shows that, luckily, a bridge had been built just south of the boundary to let a river flow under the railway. I guess the choice was to either

- build an expensive new bridge and have a straight road, or

- reuse the existing bridge, put the river underground, and live with a bend in the road!

Hung Hom

We'll skip the north-east section of the map, heading instead to Hung Hom where we can see the 1896 map again. (The straight line on the right below isn't the shoreline, it's just where the old paper map ends.)

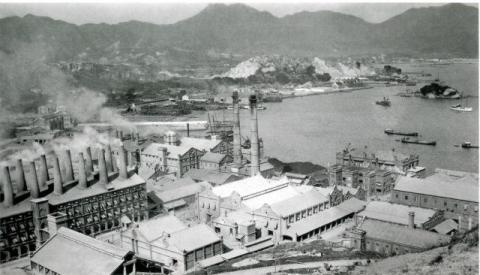

At this time the only major enterprise in Hung Hom was the Kowloon Docks.

By 1920, the dockyard - and the associated housing for its workers - had expanded.

Another major employer had set up here as well. Reclamation along the north shore of the Hung Hom peninsula provided land where Green Island Cement built their cement works.

And though the power station was still at its Chatham Road site, in 1920 work was already underway at the north-east tip of the peninsula, building the new Hok Un power station. A year later, the power station on Chatham Road site closed and operations moved to the new site.

Here's how that reclamation looks on the map - note there's a tiny part of the 1920 shoreline that still touches the sea today!

Kowloon's vanishing streams and hills

Another reason I like looking at the old maps is to get an idea of what the land looked like before all this development took place. What traces of the original streams and hills can still be seen?

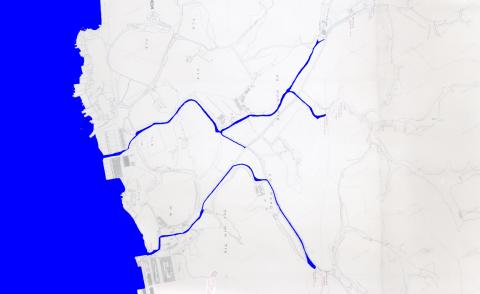

There aren't many places in today's Kowloon that you'll see running water. Kowloon's streams vanished from sight in two phases, and we can see the first phase by comparing the maps of Ho Mun Tin again.

Here I've highlighted the parts of the map that were tinted blue, showing the old streams meandering across the land until they reached the sea.

The first phase of their disappearance was to tidy them up - Government reports of the time describe the process as "training" the streams. By 1920 the wandering streams had been consolidated into one, neat, granite-lined nullah, running along the centre of Waterloo Road.

You could still see the nullah for many years, but eventually the second phase was to cover it over. The water now flows hidden from sight.

Streams can be hidden underground, but how would you go about hiding Kowloon's hills?

Digging away a hill turns the sloping hillside into flat land that can be built on. It also provides earth and rock that can be used to reclaim land from the sea - and so make even more land that can be built on. Two chances to make money from one project proved irresistible, so Kowloon's hills have steadily disappeared over the years.

Unfortunately neither the 1896 or the 1920 maps show contour lines, so there isn't a direct way to see where the hills were. We do get evidence of one of the hills though, at that point where Nathan Road narrows and curves around the base of a hill, just north of the old junction with Gascgoine Road.

Only after the hillside was dug away could Nathan Road be straightened, and the end of Gascgoine Road become a gentle curve.

Those are the highlights of the 1920 Kowloon map that caught my eye. I hope you'll also enjoy exploring the map, and share your discoveries with us in the comments below.

Further reading

- View the 1920 Map overlaid on modern maps of Kowloon. (It's also worth reading the guide to using maps on Gwulo, to get the most out of them.)

- Follow the path this 1920 map took, from the original paper map in an archive in London, through various software applications, to becoming a live, online map here on the Gwulo website.

- Explore other maps of Kowloon drawn in 1896 and 1956.

- Visit these other sources for old Hong Kong maps.

- More evidence of how quickly TST grew in the early 20th century: 1905: TST takes off.

Source

The original map is held at the UK's National Archives:

Reference: CO 1047/455

Description: `Map of the Kowloon Peninsula (including portion of New Kowloon) (New Territories) Colony of Hong Kong'. 6 sheets. Printed. 200 feet to an inch. Crown Lands and Survey Office, Public Works Department

Comments

King's Park Hill

You can see the hill on this photo from the 1910s.

Nathan Road - Gascoigne Road Original Junction

Greetings. In the 1950s when I walked on the west side of Nathan Road, I saw at or about Alhambra Theatre's southern corner a small "stand" consisting of natural rocks. It was about 3 feet wide and 4 feet high. I wonder if it was at one time a part of the hill, or moved here from excavation site for display. Regards, Peter