I've just finished adding another old paper map to Gwulo's online maps. I'll come back to the map itself in a future newsletter, but this week I'll take a look at what went on behind the scenes.

1. Decide on what type of map should be next

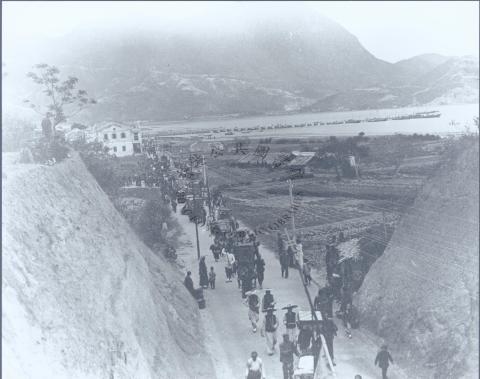

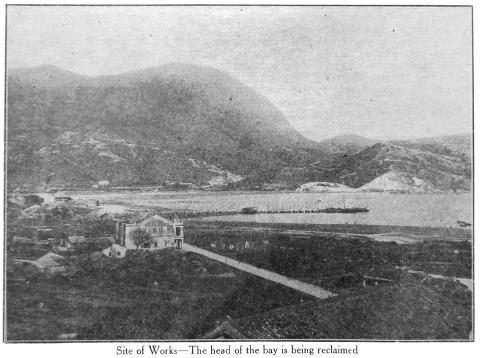

We've had several posts about Kowloon sites recently, eg the New Kowloon City Road, and the Kai Tak Reclamation, so I wanted to add another map of Kowloon.

We've already got maps showing Kowloon in 1896 and 1957, so a map from sometime in the middle of that range would be ideal.

2. Find a suitable map

The National Archives in the UK have been my main hunting ground for old maps of Hong Kong. Starting in 2009, I've visited them for a day or two each spring, using my digital camera to copy a selection of documents, maps, and photos.

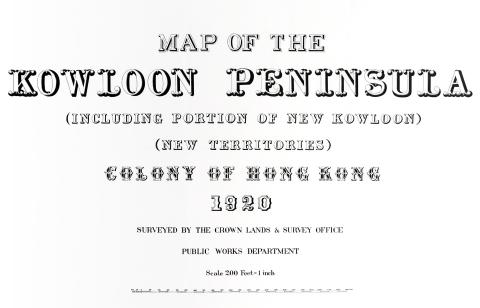

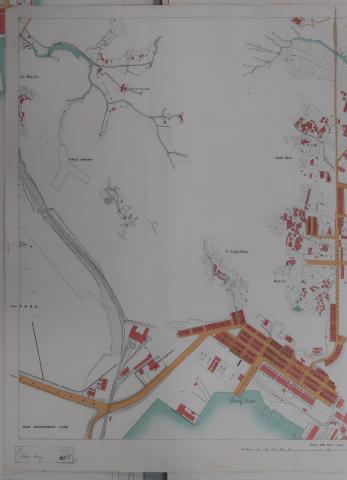

This year's trip got cancelled due to the COVID-19 travel restrictions, but I could still look back through the files from previous visits to see if there was anything I could use. Aha! In February 2018 I photographed a six-sheet map of Kowloon Peninsula, their ref: CO 1047/455. It was drawn in 1920, so will be ideal.

3. Make a single, digital map

When the Archives staff hand you this map, you get a large folder with the six original sheets inside. They've been stored flat, and in a controlled environment, so they're in great condition. I worked through the map a sheet at a time, moving my camera across each sheet in a grid, taking photos as I went.

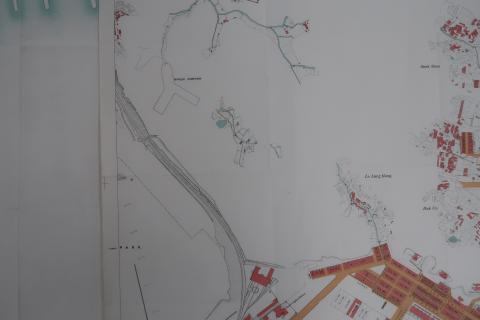

Here are the photos I took of the left edge of sheet 4 as an example:

These are already good resources - if you click on any of those photos and then on the "Zoom" tab you'll see there is lots of detail to explore. But it's clumsy to have to keep switching between photos, so I'd rather combine everything to make a single image of the whole map.

When I first tried this several years ago, I used Photoshop to combine them. It sort of works, but it took a lot of effort, especially when there are more than two photos involved. And I was never 100% happy with the end result, as it was easy to spot the joins.

Then I discovered some open-source software called Hugin. It's typically used to create panoramas, but it's also powerful enough to combine photos even when the camera was moved in between photos - which is exactly what I need.

Here's how the same three photos look after processing. See how they're no longer simple straight-sided rectangles? That's the result of Hugin using some clever maths to change the orientation of each image so that it looks as though it had been scanned on a flatbed scanner. (It also shows that although I tried to keep the camera vertical, and at the same distance from the paper, for each shot, I didn't succeed! Never mind, Hugin has fixed that.)

Then Hugin blends all the re-aligned photos together to form a single image. It does an excellent job, so it's often impossible to spot exactly where it has made the joins.

Unfortunately, you can't just throw a bunch of photos at Hugin, click "Go", and get the finished map. There's definitely a learning curve, and it has taken several hours' work to get these six sheets reassembled. But it's very satisfying to see the end results. If you'd like to try it, you can find tutorials for Hugin online, and I've also written down some tips on how I use Hugin with photos of paper maps.

At the end of that I had the six sheets. Then it was straightforward to bring them into Photoshop, align them to make one large map image, and adjust the lighting so they don't look so dark.

4. Georeference

The single-image map is a big step forward, but when I'm investigating an area of Hong Kong I want to be able to switch easily between a sequence of old and modern maps. That lets me see how the area has changed, and also work out where it is today.

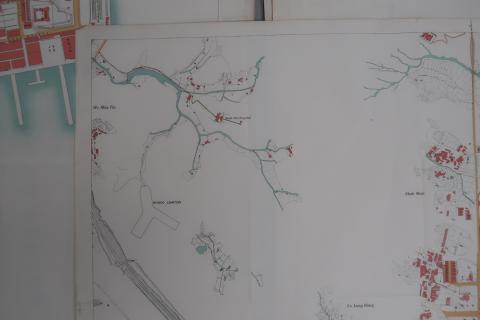

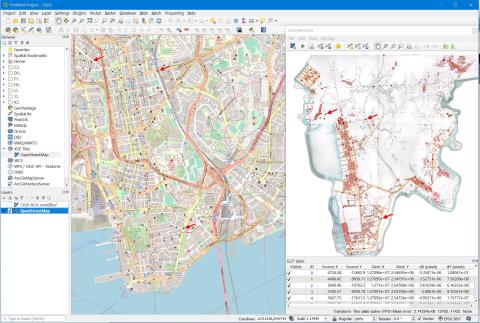

So I want to overlay this new map on our existing collection of maps. But before the computer can display the map at the right location, it needs to be told which part of the earth's surface the map shows. We do that by "georeferencing" the scanned map, and fortunately there is another open-source application, QGIS, that can help us.

After loading the scanned map into QGIS, we look for locations that we can see on both a modern online map (left) and on the scanned map (right). We click on each one to tell QGIS they're the same location, then QGIS marks them with a red dot - I've highlighted three below with arrows.

At this point there's a decision to be made: should we keep the map as scanned, or allow QGIS to "rubbersheet" it? I want to see locations on the old map as close as possible to the same location on a modern map. But I know that the old maps aren't always 100% accurate. So I let QGIS warp the original image so it fits the modern map better. (Imagine printing the old map on a thin rubber sheet, and stretching it here and there so it overlays the modern map more accurately.)

After QGIS has done its work we're left with a georeferenced image file that is 260Mb in size. That isn't something you'd want to download onto your smartphone, so we need to run it through one more piece of software.

5. Tiles

Have you ever wondered how Google Maps can quickly show you a map of the whole world? Surely that must be a huge image, so why don't we have to wait long for it to be displayed?

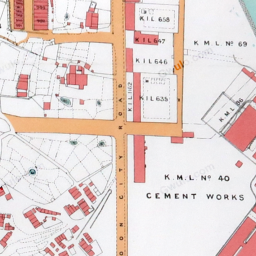

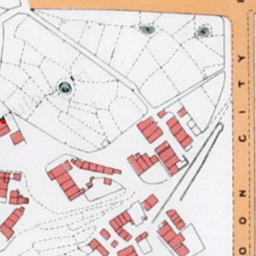

Instead of sending you a single, giant image, their trick is to cut the map into lots of small tiles. Then say you browse to a map of Kowloon, your web browser is smart enough to just download the tiles that show Kowloon, and ignore all the other thousands of tiles that are out of sight.

So our last step is to cut up that 260Mb image from the previous step, converting it into lots of small tiles just like Google does. It's a little bit more complicated than it looks, as we'll have to make one set of tiles for each of the different zoom levels. Fortunately there's software that takes care of all this for us too.

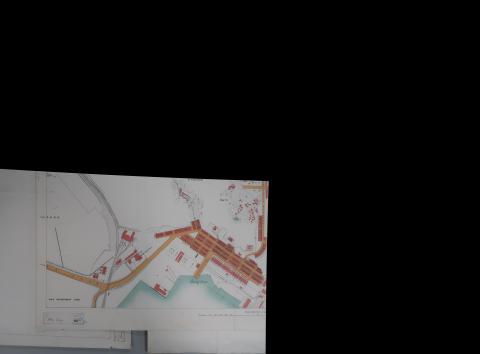

In this case, I'm using a commercial application called Maptiler, though there is also an open-source alternative, gdal2tiles. Here are some of the tiles it produced, showing how they change at different zoom levels.

6. Add it to Gwulo

Nearly there! First go and have a cup of tea while we wait for all those tiles to upload. Then add a couple of lines of code to the Gwulo website to let it know it has a new map to show. And then, ta-da: here's the new map of 1920s Kowloon.

(If you'd like to get more out of Gwulo's maps, I recommend watching this short video. It lasts about seven minutes, and shows how all the different features work.)

Comments

Congratulations

Hi David, really hard work, but worth it. We had lots of discussions about houses built 1890 to 1920 in the vicinity of Robinson/Nathan Road, so this map helps a lot for identification. And it already helped to shift the marker for the European House at the New Kowloon City Road [c.1910-????] to it's correct place.

Regards, Klaus