The following text and images originally appeared as chapter 2 of "History of Photography in China 1842–1860", published by Bernard Quaritch in 2009. (Click here for more information about the book and how to order.) This is Volume 1 of Terry Bennett's work on China's photo history. They are reproduced here with the kind permission of the author and publisher.

Chapter 2

THE FIRST STUDIOS

Hong Kong was the location of the earliest recorded examples of commercial photographic studios in China.

George R. West (c.1825–1859)

George West deserves to be better remembered. Not only does he appear to have been the first professional photographer in China, albeit a reluctant one, but he was also a fine painter as well as an adventurer who spent no less than six years travelling in disguise inside the country. His later attempt to refocus his life on a career in the diplomatic service was cut short when he died at his post at the age of thirty-four. Despite a short life, punctuated with missed opportunities and bitter disappointments, West achieved much and it is hoped that the following notes will help to bring him some well deserved, if much delayed, recognition.

Fig. 6. Engraving of an ambrotype photograph of George R. West by

Mathew Brady published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper,

16th February 1856 (p.158). Author’s Collection.

West was born in North Carolina in or around 1825. He was the son of Major Thomas L. West and Caroline M. Gales (1800–1844) who were married on 25th March 1818.12 His father seems to have come from a military background and was later a Justice of the Peace, whilst his mother was a daughter of Joseph Gales, a local newspaper proprietor and founder of the Raleigh Register.13 From the sparse information given in the US census returns for North Carolina, Wake County 1830 and 1840, it seems that West had up to three brothers and one sister.

West began his artistic career in 1842 by executing wood engravings for local newspapers in Raleigh, North Carolina and had studied engraving under Thomas P. Jones.14 A gifted artist he decided, for some reason, to open a daguerreotype studio at East St NW, near Seventh St, Washington, DC, and his studio is listed in the 1842–1843 Washington directory.15 More than fifty years later, in 1898, a fellow Washington photographer, Samuel Rush Seibert, recalled that West was one of the first daguerreans in Washington:

During the winter of 1842 and 1843 Mr George West was trying experiments to produce Daguerreotypes in a room on the north side of E street northwest, near Seventh street. In that room I think the first copper plates were silvered in a battery for that use in this city, and the first Daguerreotypes on silver plates made . . . . Mr George West was the first man to make salable Daguerreotypes in 1842 in Washington, D.C. At that early day no doubt others were trying to make them. I did not know if they were. There was no gallery open at that time except the West gallery in E street.16

Shortly afterwards, in what would prove to be a life-changing decision, West applied to join the first American diplomatic mission to China, led by the respected lawyer and politician, Caleb Cushing.

After Britain had defeated the Chinese in the First Opium War the treaty she negotiated gave certain privileges to other nations. However, the Americans wanted their own treaty and charged Cushing in 1843 with the responsibility of securing terms that were at least as favourable as those secured by Britain. Cushing was duly appointed commissioner and the United States’ first ambassador to China. West applied for, and was given, the post of official artist to the expedition, at the tender age of eighteen or nineteen. The position was unpaid and he must have hoped to be able to bring back paintings or photographs with sufficient commercial value to justify the journey; perhaps, too, the prospect of novelty and excitement was not without its attractions. Importantly, West also took his daguerreotype camera along with him.

The Cushing mission arrived in Macau harbour on 23rd February 1844. West immediately set about fulfilling his official task of sketching Chinese scenes and important diplomatic occasions, but he was also kept busy by Cushing as a messenger, carrying the envoy’s communications to the Chinese. He nevertheless was able to produce a large number of watercolour paintings and sketches, unfortunately stolen on their way to America.

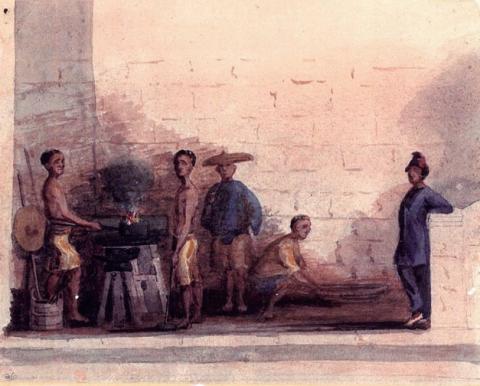

Fig. 7. George R. West. ‘Chinese Blacksmiths. Macao,’ 1840s. Watercolour.

Caleb Cushing Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Cushing secured the desired treaty which was signed in the village of Wanghia in Macau on 3rd July 1844. The following month the mission left China to return to the United States. West declined the free passage home since he wanted to spend more time building his portfolio. It seems clear that he had very little spare money but had calculated that he had just enough with which to return home. However, fate intervened and West ended up spending the next six years in China. A surviving letter addressed by West to Cushing in December of that year is revealing:

Canton, December 1844.

Dear Sir,

The ship ‘Moslem’ I left Macao in with the intention of going home in her via Manila was found after arriving in Manila to be rotten or defective in the timbers – so I abandoned her & came to Macao with the intention of immediately sailing for home, but having to wait some time for an opportunity until my money became so reduced as not to leave sufficient to pay my passage home. I am now in Canton making use of the Daguerreotype instrument in connection with painting which I hope will soon enable me to return home. With much Respect yours truly Geo. R. West.17

It is not clear whether West was using his camera as an aid to his own painting or taking daguerreotype portraits of local residents. If the latter, this may have been preparatory to his customers having their portraits painted, life-size, by Chinese artists. Loaning a daguerreotype portrait to a Chinese painter to copy was an effective means of avoiding the inconvenience of attending several lengthy sittings (see, for example, Düben and Saurman’s advertisement in the North China Herald, 24th September 1852, quoted below, p. 23).

Having exhausted his financial resources on accommodation and subsistence, West was using his camera commercially in order to survive. He was no doubt also trying to sell sketches and paintings to local residents. By December 1844 at the latest, he had almost certainly thereby become the first commercial photographer in Canton and, by extension, China. Perhaps he also took photographs in Macau at this time, but he must have decided quite quickly that the foreign communities in Canton (Guangzhou) and Macau were too small to provide him with a sufficiently viable customer base. Judging by the list of names in the 1845 edition of the Chinese Repository there were only around 100 foreigners living in Canton at this time, and a still smaller number in Macau. West therefore turned his attention to the more dynamic and fast-growing colony of Hong Kong. And it is now all but certain that the previously unidentified photographer in the following advertisement is George R. West:

Mr West begs leave to inform the inhabitants of Victoria that he has opened a Photographic or Daguerreotype Room in Peel Street, near Queen’s Road. His room will be open from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m. Single miniatures $3. $2 charged for each additional head in a group. China Mail, 6th March 1845.

Subsequent advertisements, which continued until 10th April 1845, showed an address of Sydenham Terrace, rather than Peel Street. It is unclear how long West operated this studio, but it is doubtful that it continued more than a few months. By late 1845, or early 1846, both the Carl Smith Archive (in the Hong Kong Public Record Office) and the 1846 edition of the Chinese Repository show he was working for the Hong Kong-based American merchants, Bush & Co.

As mentioned above West’s sketches and paintings were stolen on their way home to America, a misfortune that seems to have motivated him to produce replacements. It is not clear whether he received an official commission to do so, but some 124 of his paintings are held today by the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. In order to accomplish this task he left Hong Kong in 1846 and embarked on a prolonged period of travel in and around the open treaty ports of China, sketching furiously wherever he went. It appears that he occasionally received patronage from the foreign residents at the ports because he stayed in China, working as an artist, for approximately six years.

We have very little idea of George West’s movements during his roving years in China and are indebted, therefore, to the American physician, Benjamin Lincoln Ball, who travelled around China in the years 1848–1850 and accompanied one of West’s excursions, as recounted in chapter 30 of his book Rambles in Eastern Asia (1855). Ball first met West in May 1849 in Shanghai, where we know West had been since at least the previous month, because he painted the spring race-meeting of that year and the painting has survived.18 The two met next in Ningpo (Ningbo) on 12th July. The following day Ball records in his Rambles (p. 250):

I found Mr West staying at Mr Way’s [an American missionary]. He is engaged in sketching various scenes about Ningpoo, and he leaves this afternoon for an excursion into the country. Learning as much as possible about places, people, &c., and as I wished to make a trip into the country, we concluded to go together.

For their journey they packed a bag of copper coins to pay for food, lodging, and transportation and took with them three Chinese – two personal servants and a cook. They travelled inland to the Yangdang Mountains by boat, sedan chairs and on foot. Along the way they were able to appreciate some spectacular scenery, but were less enthusiastic about the close attention paid to them by numerous Chinese they met, many of whom were apparently seeing white foreigners for the first time. Just the presence of the two Westerners was by itself sufficient to draw a crowd and particular interest was aroused by West’s rapid sketching activities – Ball mentions that they were often surrounded by crowds because West seemed to be sketching non-stop. Despite Ball being a wonderfully descriptive and detailed writer, we learn little from him about George West beyond that the artist was devoted to committing as many Chinese scenes to paper as possible. There is no evidence of any particular closeness in their relationship and perhaps as individuals they had little in common.

West returned to the United States in 1850 or 1851 and he brought back with him a large portfolio of paintings and sketches. He may have had discussions with publishers about turning these into a volume of lithographs or engravings with an account of his journeys, which would certainly have been a promising format for a popular travel book. But West gambled on a more ambitious scheme. He decided to convert his hundreds of illustrations into a panorama of China, a giant panoramic painting that he would exhibit around the country.

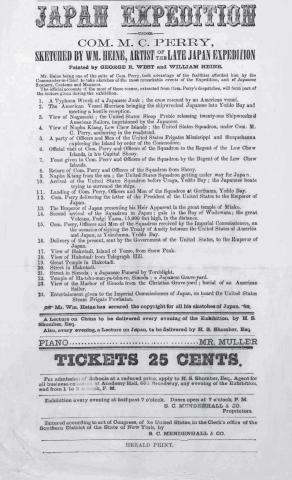

At this time in America and Europe panoramas were popular forms of entertainment. They could present the viewer with enormous vistas of attractive scenery, views of foreign countries, or reconstructions of famous battles. In 1849, for example, New Yorkers had been able to appreciate a panorama of the River Nile. Audiences would watch as gigantic painted canvases were slowly unrolled as a lecturer simultaneously delivered an informative and entertaining commentary. Large canvases gave the illusion of actually being present at the location, creating a form of vicarious travel. Some were as high as twelve feet and as long as one mile. West’s panorama no longer exists, but we know that his canvas was some 20,000 square feet and it is possible, therefore, that it extended to more than one third of a mile. We can imagine that its various scenes portrayed a positive view of China and the Chinese, but West was unlucky in his timing: the Chinese were increasingly held by Westerners to be backward and ignorant, foolishly clinging to outdated customs. Moreover, after Commodore Perry’s expedition and the treaty concluded with America in 1854, Japan had been partially opened to the outside world. China was considered to be a far less appealing destination and it was Japan that now captured the public’s imagination. West, therefore, discussed the idea of a joint China and Japan panorama with Wilhelm Heine, the German-born official artist accompanying Perry’s squadron. Having agreed terms, they hired two other artists to help them prepare the canvas and on 26th January 1856 their panorama was unveiled at the Academy Hall, Broadway, New York.

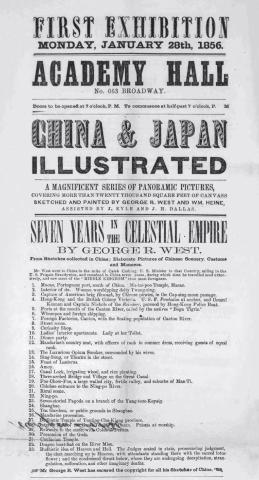

Fig. 8. Broadsheet advertisement for West & Heine’s panorama

of China and Japan, exhibited for the first time on 28th January 1856

at the Academy Hall, Broadway, New York.

A colourful and informative report of West’s sojourn in China was printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 16th February 1856 (p. 158):

GEORGE R. WEST, the Chinese Traveller and Artist, of West and Heine’s Excursion to China and Japan.

China has now arrived at the most critical period of her history, and every inquiry related to it is pregnant with peculiar interest to the civilized world. China is the oldest, and America the youngest nation. Every day brings forth information that adds to our knowledge of the ‘Celestials,’ and though they are whimsical and full of anomalies, they are understood. Our California possessions bring us within a few days of her shores – the Cushing Treaty – the emigration of Chinamen to our land, the promised opening of trade with Japan and the increasing demand for our products, together with other influences, have materially changed our relations, and invested China and Japan with an absorbing interest. In the year 1843, George R. West, a native of Raleigh, N.C., embarked for China as an Attaché of the Hon. Caleb Cushing’s Embassy, as Artist to the Expedition. In this capacity he made a series of sketches for the U.S. Government, embracing scenes in the various ports visited by the squadron, as well as pictures of Chinese social life. These sketches, forming a magnificent series, were lost, together with the personal property and government manuscripts of the Hon. Caleb Cushing, when he was robbed by banditti, when homeward bound he passed through Mexico, on his way to Vera Cruz. This robbery has always been considered by those acquainted with Santa Anna to have been his work. Mr West, whose spirit of enquiry was not satisfied when the American squadron returned home, remained in China, and there heard of the misfortune that had occurred to Mr Cushing. Having no duplicates of his drawings, he conceived the idea of remaining in the empire and producing a new series, and thus repair the loss the country sustained in the robbery of our minister. To accomplish his wishes, being no longer under government protection, he was obliged to disguise himself and adopt the Chinese costume and habits. Having a clear olive complexion, dark eyes and hair, his transformation was complete. Securing the services of a faithful native servant, and generally affecting to be deaf and dumb, Mr West wandered for seven long years through various parts of the Chinese Empire, visiting places never before seen or known to Europeans. The result of this privation, personal danger and magnificent enterprise, was a portfolio of three hundred and fi fty sketches, including scenery, religious festivals and social life, which pictures have formed the basis of Mr West’s Panorama, now open to the New York public.

As an instance of the vicissitudes through which Mr West passed, we may mention, that at one time he was sailing in the China Sea, when his vessel was attacked by pirates, and his Portuguese companions murdered. Mr West made a bold defence, and the freebooters agreed to save his life if he would yield without further resistance. The pirates then seized and stripped him of his clothing, lashed him to a sofa in the cabin of the junk, robbed him of all the money he had, cut down the boat’s sails, and threw them, with the anchors and chains, overboard, leaving the vessel to the mercy of the elements. By extraordinary exertions, with the men forming his crew, whose lives had been spared, [they] reached a place of safety. He then found himself entirely destitute of clothing, money, or any apparent means of extricating himself from his difficulties, yet he was not discouraged, nor, for one moment, turned aside from his determination to carry out his projects of illustrating Chinese life with his pencil ....

The costume Mr West traveled in, was a disguise which denoted him a small merchant or trader, made of very plain material, and no way distinguished from the common people. His cap was in the shape of that worn in the costume represented, but without the honorable distinction of the button on the apex, and the still more important appendage of a peacock’s feather.

This article raises some questions. Exactly how long did West stay in China? When he returned to America in 1850 or 1851 what did he do between then and the opening of his panorama in 1856? Did it really take five or so years to prepare his canvas? Perhaps he re-opened his Washington photograph studio in the meantime. In any case, the panoramic exhibition opened to mixed reviews and closed towards the end of the year. This must have been a major disappointment to West who now found that his grand project had left him with nothing to show for it. Such an exhibition was, by definition, an ephemeral event and perhaps West was now regretting not having turned his artistic endeavors into something more tangible and permanent. He must have thought himself fortunate, therefore, to receive at this time an offer to participate in a seemingly prestigious government-commissioned painting project in Washington, DC.

In the 1850s the US Capitol Building was being extended and re-decorated. Montgomery C. Meigs, a captain of engineers trained at West Point, was overseeing what was an enormous project. Meigs was fond of Italian Renaissance art and wanted the walls and domes of the new interior to be painted in this style. He hired Constantino Brumidi, a classically trained painter, to undertake the task. However, Brumidi needed help and George West was hired to paint sketches drawn by the Italian of important naval engagements which were destined to adorn the walls of the rooms of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs. West, who had a high opinion of his own artistic ability, seemed to find his role of being Brumidi’s assistant demeaning and also felt that he was being underpaid. A dispute between the artist and Meigs arose which escalated into West’s taking the position that he had been insulted. He destroyed the six naval scenes he had almost finished and walked away from the project.

West now helped to found the Washington Art Association which was in operation from 1856–1860.19 Its purpose was ‘to promote the progress of art through the co-operation of the artists and the citizens of the seat of Government and the United States, and to encourage and advance the Fine Arts.’ West was one of its officers and his position was that of ‘recording secretary.’20 One early action taken by the Association was to petition the government, complaining that the work at the Capitol Building was under the direction of an engineer, rather than an artist. Establishing the Association would have taken up some of West’s time but he must have been considering which direction his future life would take. Did he now turn to his old friend Caleb Cushing who had risen to the post of United States Attorney General? In any case he was offered the minor diplomatic role of United States consul for New Zealand. His career as an artist had stalled and photography did not seem to appeal. Perhaps West felt he could build on the small amount of diplomatic experience he had gained under Cushing.

West received his consular passport in October 1856. However, he wrote to the State Department asking that his departure be delayed until January as he had some personal affairs to take care of. In fact he did not leave for New Zealand until 12th August 1857. The consulate was situated in the Bay of Islands but West asked for discretion to move it to the capital, Auckland, should that prove to be a better location.

West arrived in New Zealand on 31st January 1858 and, in the event, decided that the existing location was the most appropriate since it was the main port visited by American whaling ships. In the consular dispatches we can see that West wrote to Washington on a number of issues. On 6th July he reported that: ‘Upwards of seven hundred of the whaling vessels are engaged in the whaling trade out of the States which is more than all the rest of the world combined most of which cruise in these seas.’ He complained that: ‘All the houses of this town are of wood and very poorly constructed; the troops have been removed from here; we are completely at the mercy of the natives and liable at any time to have our house burnt or pillaged.’ On 15th July he offered his opinion on the native population: ‘The Maories or natives are a lazy drunken race resembling much in that respect the North American Indians. They are too indolent to work for themselves unless forced to it by necessity and too proud to work for the Whites.’ Also in the consular archive there is an incomplete letter without a date or addressee’s name in which West writes to ‘my dear brother’ and asks to be remembered to their relations in Washington.21

Looking out from the consular office window to the American whaling ships moored in the harbour below, George West might have reflected on an adventurous life and the twists of fate that had brought him to New Zealand. Did he regret some of the major decisions he had made in the past, or was he perhaps contented and looking forward to a long and successful diplomatic career? We shall probably never know. The following notice of his death appeared in the New Zealander newspaper on 8th June 1859:

WEST. At Russell, Bay of Islands, on 28th May 1859, of consumption, aged 34 yrs, George R. West Esq., Consul for the United States of America in New Zealand.

There were no obituaries in the main newspapers. Some months later the news had fi ltered back to the United States. The Louisiana Daily True Delta made a simple announcement of West’s death in its issue for 18th October 1859:

Death of a Consul – The Department of State has received information of the death at the Bay of Islands, on the 28th of May last, of Mr George R. West, the United States consul for New Zealand. The vice-consul states that ‘Mr West was highly esteemed for his amiable and gentlemanly deportment.’22

The 19th October 1859 issue of the Weekly Raleigh Register, a newspaper founded by West’s maternal grandfather, gave an equally short notice:

Died. On the 28th of May last, of Pulmonary Disease, at the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, George R. West, U.S. Consul at that point, in the 36th [sic] year of his age. Mr W. was a native of Raleigh, but had resided for several years, previous to departing on his mission to New Zealand, in Washington City.

There are no known surviving photographs taken by West. Fortunately a significant number of his paintings remain, but knowledge of these is largely confined to those with an interest in early China-Coast art. John Haddad, chapter 7 of whose book, The Romance of China (2008) includes an informative account of George West in China, assesses West’s art as offering ‘a construction of China that is positive, uncritical, and often humanistic. A general fondness for China suffuses the entire body of work, but one would not characterize it as overly idealized; rather, West seems to have captured China as it appeared on a sunny day’ (p. 216).

George West may have left no written account of his travels and has faded into obscurity, but during a short but adventurous life he secured the distinction of becoming the first professional photographer in China.

The Daguerreotype and Lithographic Printing Establishment

As pointed out by Clark Worswick in his Imperial Chinese Photographs (1978, p. 134), a photographic and printing establishment advertised itself in Hong Kong in the 8th October 1846 issue of the China Mail:

DAGUERREOTYPE AND LITHROGRAPHIC [sic]

PRINTING ESTABLISHMENT, WELLINGTON TERRACE.

DRAWINGS of all Descriptions, Engraved and Lithographed; COLOURED or OUTLINE VIEWS made of HONGKONG or CHINA SCENERY; TRANSFER PAPER furnished to parties wishing to write their own CIRCULARS, and printed off at a few Hours’ Notice; BILLS of LADING, BUSINESS CARDS, and BINDINGS re-printed with neatness and despatch. Daguerreotype Room open from 9 a.m., until 3 p.m.

Victoria,

7th October, 1846.

This advertisement, like George West’s, ran for a short time only and last appeared in the local press on 19th November 1846, with the name slightly changed to ‘Daguerreotype Gallery and Lithographic Printing Establishment.’ The owner of the business has not yet been identified, but given the reference to drawings and views of scenery we cannot discount the possibility that the proprietor was George West.

Hugh Mackay (c.1824–1857)

Photo-historians had long assumed that the Scotsman, Hugh Mackay, who advertised a daguerreotype room in Hong Kong in 1846, was the earliest commercial photographer in China. Edwin Lai, the noted expert on early photography in Hong Kong, has now drawn our attention to the earlier 1845 advertisements of ‘Mr West’ (see entry for George West above) and has even suggested that Mackay may not have been a photographer.23

Some information on Mackay’s life can be gleaned from an obituary which appeared in the Shasta, California, newspaper, The Republican, on 21st March 1857:

Death of Hugh Mackay

We announce, with much pain, the demise of HUGH MACKAY, Esq. His death occurred at his residence in Horsetown on Wednesday last, March 18th, 5 o’clock P.M. At the same hour, on the previous evening the deceased was on the streets of Horsetown – apparently enjoying the usual excellent health. During Tuesday night he was attacked with inflammation of the bowels and on the evening first named he was a corpse. Mr MACKAY was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. He resided for some years in Hong Kong, China. In 1849 he came to California, and in 1851 settled in this County. He was a prompt and reliable merchant, an affable and upright gentleman and a citizen whose worth is rarely equaled. He was 33 years of age and leaves a widow to mourn his loss.

The remains of the deceased were brought to this place and buried by the I. O. of O. F., of which Order he was a member.24 The funeral sermon was preached by Rev. Mr Kellogg. A large concourse of citizens of Horsetown and Shasta were in attendance.

Little is known of Mackay’s life before his arrival in China. Lai suggests that he reached Hong Kong in 1845 and cites an advertisement which appeared in the China Mail on 26th June 1845. It was placed by James Miller, a resident foreign merchant of Hong Kong, who announced that he was disposing of his general goods store, situated at Oswald’s Row, Queen’s Road, to Mackay & Co. The firm offered a very wide range of goods including clothing, foodstuffs, wines, books, stationery and perfumery. In fact, Mackay must have arrived the previous year since he is listed as a foreign resident of Hong Kong in the Chinese Repository for 1845 (which was typically compiled at the end of the previous year) and the Carl Smith Archive (Hong Kong Public Record Office) refers to his being a witness to the partnership dissolution of an unrelated business on 17th July 1844. Although Smith does not name his source it is likely to be from a local newspaper, possibly the China Mail. The 1846 Hongkong Almanack and Directory lists Mackay & Co. as ‘store-keepers’ and Andrew Dixson is shown as Mackay’s partner. Another name mentioned, Frederick Cooper, is likely to have been an employee. The partnership continued until its voluntary liquidation on 14th March 1849, referred to in the issue of the China Mail of the same day.

In considering Hugh Mackay’s role in the early development of photography in Hong Kong, reference should be made to the life of his partner, Andrew Scott Dixson, who also came from Edinburgh, where he was born on 13th October 1821. According to Frank King’s Research Guide to China-Coast Newspapers (1965, p. 59), Dixson had been trained as a printer and arrived in Hong Kong in 1845 with his fellow Scot, Andrew Shortrede, who set up the China Mail newspaper in the colony that February. Dixson acted as assistant editor and manager. In 1846, as we have seen, he also joined Mackay & Co. as a partner and, after the dissolution of that partnership in 1849, he launched his own newspaper, Dixson’s Hongkong Recorder in 1850. Before that he was initiated as a Freemason at the Zetland Lodge No. 768 in Hong Kong on 7th November 1849 where he was described as a printer. At this time Dixson was still with the China Mail and, by 1854, was effectively exercising editorial control. Shortrede left China in 1856 and Dixson became a partner in the parent company. He assumed complete control in 1858.

King states that Dixson was a crusading editor who was sympathetic to the rights of the Chinese living in the colony. He fiercely opposed the then prevalent ‘coolie trade’ which was providing a lucrative income for some Macau traders who were engaged in the illegal forced emigration of unsuspecting Chinese workers. Dixson contributed to the colony’s cultural life by acting as Secretary to the Reading Room and Library. In 1858 he hired an editor and spent some time travelling; he met and married his wife in Scotland on 10th September 1860. Back in Hong Kong he began to suffer from ill health and was forced to sell his company in 1863 and return to Scotland. The 1871 Scotland census identifies Dixson living in Elie, Fife as a forty-nine-year-old retired newspaper proprietor. He is shown as living with his wife, called Jeannie, aged forty-four and a native of Elie. Also living with them were a family boarder, a servant and their eight-year-old son, Douglas Scott, who is recorded as having been born in Hong Kong. Andrew Dixson, after an enterprising and colourful life, died in Elie on 6th June 1873, aged fifty-one.

From its formation in June 1845, Mackay & Co. advertised its goods extensively in the local newspapers. The China Mail, for example, carried a daily advertisement for the firm. Bearing in mind Dixson’s continuing editorial role and involvement at the newspaper, we can assume that this advertising was placed free of charge or at a reduced rate. Considering the daily pressures of editorship of a newspaper such as the China Mail, we can also assume that Dixson’s partnership in Mackay & Co. was passive, with day-to-day management in the hands of Mackay himself; as Edwin Lai suggests, Dixson probably had only a minority stake in the business.

Business was apparently good and eighteen months later, on 10th December 1846, the China Mail advertised two additional services:

MACKAY & Co. respectfully intimate that they have added to their establishment a Lithographic Press, and are prepared to print upon the shortest notice any orders they may be favored with.

Hongkong,

7th December, 1846.

DAGUERREOTYPE Portraits accurately taken in a few minutes at, MACKAY & Co.’s

Hongkong,

7th December, 1846.

There can be little doubt that Mackay & Co. had acquired the Daguerreotype Gallery and Lithographic Printing Establishment which had last advertised its services less than three weeks earlier (see above, p. 15). With his printing background, we can assume that Dixson would have understood all aspects of the lithographic service. The question is: who was the photographer? Worswick has made the not unreasonable assumption that Hugh Mackay was responsible (Imperial China Photographs, 1978, p. 134). Lai is not so sure (‘Hugh Mackay and Early Photography in Hong Kong,’ History of Photography, vol. 27, no. 3, Autumn 2003, pp. 289–93). He points out that the daguerreotype service was only advertised for two months – the last time in the China Mail on 21st January 1847. Only six months later Mackay was trying to sell the equipment, as can be seen in the China Mail for 1st July 1847:

FOR SALE.

TWO LITHOGRAPHIC PRESSES in complete working order. Purchasers of both or either of the above PRESSES, will be made acquainted with their Practical use; and will also be shewn the method of preparing the several articles required for LITHOGRAPHIC PRINTING.

Also, Two Large STONES; Black and Coloured INKS; VARNISH and a quantity of TRANSFER PAPER.

ALSO, A DAGUERREOTYPE Instrument, for taking PORTRAITS and VIEWS, with CHEMICALS and PLATES for Several Hundred PICTURES. The Buyer, if required, will receive such Instructions from the Party now using the Instrument as will enable him to take PORTRAITS and VIEWS with the utmost facility.

Apply to MACKAY & Co. Queen’s Road.

Hongkong,

1st July, 1847.

The phrasing of this advertisement suggests that the current user of the daguerreotype instrument was someone other than Mackay. The previous owner of the equipment must be a possibility, and George West cannot be ruled out. The firm’s employee, Frederick Cooper, may also have received some past training in photography.

Despite this failure, Mackay & Co. continued to look at other business opportunities. It is probable that the core general retailing business was sufficiently robust to encourage new ventures. At the beginning of 1847 the firm published The Victoria Almanack and Chinese Directory which, naturally, was promoted by Dixson in the China Mail on 14th January. A more ambitious, and no doubt capital-intensive venture, was the opening of a branch store and private hotel for shipmasters at No. 1, New French Hong, Canton (Guangzhou). The Carl Smith Archive (Hong Kong Public Record Office) indicates that the operation was run by Wilson Hunt who was also a partner in the enterprise. It was initially advertised as an establishment that would welcome captains of vessels and strangers visiting Canton, but that the owners would ‘not allow it to become a place of general resort, or assume the character of a Tavern’ (China Mail, 21st October 1847). As Edwin Lai (‘Hugh Mackay and Early Photography in Hong Kong,’ History of Photography, vol. 27, no. 3, 2003, p. 291) has pointed out, by October 1847 the firm was advertising itself as ‘Mackay & Co., Hongkong and Canton.’ From the China Mail for 20th January 1848 that firm can be seen to have moved into new premises in Hong Kong and was promoting its extensive range of goods, which were also to be had at its branch in Canton. However, by 8th June the China Mail reported the closure of the firm’s Hong Kong operations and, on 14th March 1849, the dissolution of the partnership of Mackay & Co.

It is unclear what motivated Mackay to leave Hong Kong later that year and head for California. It is very likely, however, that he had caught ‘gold-rush fever’ and was one of the estimated 300,000 migrants to California who were searching for their share of the newly discovered gold. Benjamin Lincoln Ball, the Boston physician was travelling in China at this time and had received news from America about the excitement in California. The letter that he wrote back home to his brother from Shanghai on 28th June 1849, whilst in a humorous vein, nevertheless captures the mood of the time, both in America and China:

My Dear Brother J.:

I have seen the Boston papers . . . which had date up to February last, and observe that a terrible disease has broken out among you, carrying off hundreds, and I know not but thousands. It has prevailed here to a greater or lesser extent. Many of the foreign population have been taken away, and the Chinese considerably subject to it. I am a little affected myself, but was soon able to arrest its progress. I know not how it is at home; but here it indiscriminately affects all classes . . . . The brain is almost invariably the seat of the disease . . . . Last week a whole ship’s company was carried off . . . . There were between one and two hundred on board, upwards of a hundred Chinamen.25

Nearly all foreign merchants living along the China Coast were driven by the desire to make their fortunes from trading within a few years, and then return home to Europe or America. Many failed or were broken by ill-health, often brought on by unfamiliarity with the local climate. Perhaps Mackay had been successful in the five years away from home. In any case he headed for California, either for gold or en route to Scotland. The 1850 United States census for Sacramento City, California, lists a twenty-six-year-old Hugh Mackay, a trader born in Scotland. The return indicates that he owned real estate valued at $1300. This may well be the same Hugh Mackay who would find his final resting place a long way from Edinburgh. Although he enjoyed a successful, if short, business career in Hong Kong, Mackay’s failure with the daguerreotype shows that China was not yet ready to support a full-time photographic studio.