The following text and images originally appeared as chapter 1 of "History of Photography in China: Western Photographers 1861–1879", published by Bernard Quaritch in 2010. (Click here for more information about the book and how to order.) This is Volume 2 of Terry Bennett's work on China's photo history. They are reproduced here with the kind permission of the author and publisher.

Chapter 1

HONG KONG STUDIOS

Introduction

At the beginning of 1861 photographic studios were coming to terms with the sharp decline in business following the withdrawal from China of thousands of British and French military personnel who had recently been deployed in north China during the Second Opium War. The Americans, Weed and Howard, took advantage of the lull by exploring the treaty ports of Canton (Guangzhou) and Shanghai, setting up temporary studios in order to test the demand for their photographic services, meanwhile leaving their Hong Kong studio in the more than capable hands of Milton Miller, their operator and caretaker manager. It seems that the future plans of all three photographers at this time were in a state of flux.

Exactly what conclusions the Americans reached are not clear, but in September 1861 Weed (and possibly Howard) returned to America. Before leaving they secured the services of the Englishman, Charles Parker, in August 1861. From September, Miller was the owner and manager of the recently opened Weed & Howard studio in Canton, and it is probable that Parker took care of the Hong Kong business. Whether Parker subsequently opened his own Hong Kong studio for a few months before departing to Japan in early 1863 is not certain. (For further information on Weed and Howard, Milton Miller, and Charles Parker, see History 1842–1860, pp. 106–10, 163–79.)

From late 1861, through until the end of 1862, it seems that Milton Miller and Charles Parker were the only recognised commercial Western photographers in the British colony, with Miller dividing his time between Hong Kong and Canton. The two photographers did not have a complete monopoly at this time, however, and at least three other studios, albeit shortlived, are known to have set themselves up in competition. The earliest was probably that of G. E. Petter, who first advertised in the 7th August 1861 issue of the China Mail:

PHOTOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION.

415 Queen’s Road East,

Opposite H.M. Dockyard.

MESSRS. G. E. PETTER & CO. beg to announce the opening of the above for the following purposes: –

aking Portraits, Views, and Stereoscopes, on Paper or Glass. Copying Engravings, Paintings, Photographs, &c.

The Sale of Cameras, Lenses, Baths, Tripod Stands, Prepared Frames, Glass Plates, Albumen Paper, Morocco Cases and Mounts, Pure Chemicals, and every requisite for The Art, all of the most approved construction, at moderate prices.

Instructions given in all processes.

Negatives printed from.

As Messrs. P. & Co. trust that the above Establishment will be permanent, all Negatives of Paper Portraits will be kept and registered, so that Duplicate Copies may be obtained at any time on application.

Hongkong,

7th August, 1861.

There is no trace of Petter operating as a photographer in Britain prior to this and no photographs by him have been identified. His final advertisement appeared two months later, on 17th October 1861. It is likely that he set out for Hong Kong from London in June or July 1861, since the London & China Telegraph for 15th August 1861 reported his arrival in the colony.

It has previously been thought that the Dinmore Brothers’ photographic presence in China was restricted to a studio which they opened in Shanghai in 1864. However, a recently discovered carte de visite has a Dinmore Brothers Hong Kong imprint and it now appears that the brothers also operated a studio in Hong Kong, c.1861. How long the business survived there is not certain, but it is likely that it had closed by 1863.

At around the same time a French photographer, J. Dalmas Laguenière, was listed as having a studio in the 1862 China Directory. Again, we have no information on him although he may have been the ‘Lagarriere’ who arrived in Hong Kong on 11th February 1860 (North China Herald, 25th February 1860, p. 30) or the ‘Lagarliere’ who arrived in Shanghai from Hong Kong on 11th April 1860 (North China Herald, 21st April 1860, p. 62). No photographs by Laguenière have been discovered.

A new phase of photography in Hong Kong began after Parker and Miller left China in 1863. Weed and Miller had set very high standards and any photographer wishing to survive in the colony would have to show real commitment and talent. The first studio to open in Hong Kong after Miller’s departure seems to have been that of his former associate, S. W. Halsey.

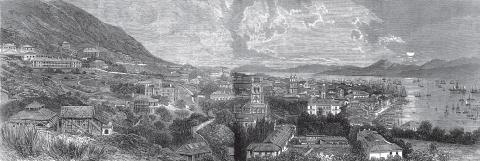

Fig. 1.1. Anonymous. Hong Kong Harbour, c.1875.

Three-plate albumen-print panorama.

Author’s Collection.

S. W. Halsey (fl . 1863–1865)

On 5th January 1864 the Hongkong Daily Press announced the opening of a new photographic studio:

NOTICE. The undersigned late of the Firm of MILLER & CO., Photographers, beg to inform the Community of this Colony that they have opened a GALLERY in the house No. 68, Queen’s Road nearly opposite the Oriental bank, and are prepared to practise Photography in all its branches on an extensive and improved scale. Their Stock of Appliances and Materials embrace all the latest improvements and inventions. All orders for taking Views of Houses, Landscapes, Shipping, Likenesses of Horses and Favorite Animals, &c., will be promptly and attentively executed.

S. W. HALSEY & CO.

Hongkong,

4th January, 1864.

This notice was followed up by an even more informative advertisement, placed in the same newspaper on 14th April, which ran until at least 9th June 1864:

PHOTOGRAPHY.

The undersigned having recently purchased all the negatives taken by Messrs. Weed & Howard, and Messrs. Miller & Co., during their stay in China, beg to inform the Community, that they can supply duplicate copies of and Portraits, Groups of Firms, &c., taken by the above mentioned Artists; also Splendid Panoramic Views of Hongkong, Canton, Macao, views of Pekin, Shanghai, Foochow, and Groups of Chinese and Japanese Characters. Views of Private Residences, Public Buildings, Ships, and all objects of interest photographed in China and Japan during the last four or five years, to which they invite inspection.

They have also received a large assortment of the best instruments, fitted with all the newest improvements, with which they are prepared to take Portraits and Groups in the most approved style. Pictures of Houses, Ships, Favorite Animals, &c., on the shortest notice and at reasonable charges.

They have likewise for Sale, – Cameras and Lenses, of all sizes and descriptions. Chemicals of the purest quality. Iodized Collodion and Nitrate of Silver Baths, prepared by themselves, and all the requisites for the various Photographic Processes at moderate prices.

S. W. HALSEY & CO., Queen’s Road.

Hongkong,

13th April, 1864.

Another major advertisement was published in the Hongkong Daily Press on 3rd September 1864:

PHOTOGRAPHY.

MESSRS. S. W. HALSEY, & CO. in returning their thanks to the community for the patronage so liberally bestowed upon them, beg to intimate that they have removed to those extensive premises formerly occupied by Mr. F. G. Reed, directly opposite the Oriental Bank, where they are prepared to take portraits, groups &c in a style equal to any European productions.

Messrs. S. W. HALSEY, & CO. have taken great pains in fitting up the gallery and waiting rooms, and beg to call the attention of the public to the fine collection of Panoramic and other views of Hongkong, Canton, Macao, and other places of interest in China and Japan, especially several very fine coloured photographic views of Hongkong &c. now ready for inspection. Cameras, Lenses, Chemicals, and every requisite for the practice of the art of Photography in all its branches constantly on hand for sale.

Hongkong,

15th July, 1864.

Having worked with Miller and having acquired Weed & Howard and Miller’s negatives, Halsey would have had the experience and a substantial stock to enable him to dominate the studio scene in Hong Kong, at least as far as Western studios were concerned (given the range of photographic equipment and supplies on hand and described in his advertisements, it is also possible that Halsey acquired the stock and business of G. E. Petter). His only serious competitors were probably the Chinese studios of John Hing-Qua and Pun Lun. However, we do not know how successful his studio really was, or the extent of the capital outlay required to obtain the negatives in the first place. The Illustrated London News published one of his Hong Kong panoramas as a wood-engraving on 16th May 1866, but no original photographic prints have been firmly attributed to Halsey.

Fig. 1.2. S. W. Halsey & Co. ‘General View of Victoria, Hong-Kong.’

Wood-engraving after a photograph by Halsey & Co. from the

Illustrated London News, 5th May 1866. Author’s Collection.

Halsey is listed in the 1865 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, Philippines etc. as ‘S. W. Halsey & Co., Photographers, Queen’s Road.’ In mid 1865 the business was sold to José Joaquim Alves Silveira, who appears in the 1864 and 1865 Hong Kong jury lists as ‘Mr Halsey’s clerk.’ No more is heard of Halsey. Why Halsey disappeared from the Hong Kong scene after such a relatively short time is something of a mystery, as are details of his personal life. There may be a link with the Halsey family of American photographers who worked in Mexico in the 1840s, and there was an A. H. Halsey who worked in Quebec in 1840.

José Joaquim Alves Silveira (1840–1874)

The American researcher, Carl Smith, established that Silveira was Portuguese, born in 1840 and died in Hong Kong, aged thirty-three on 25th February 1874 (Smith Archive, Hong Kong Public Record Office). He joined S. W. Halsey’s photographic studio as a clerk in 1864. In 1865 he purchased the business, including presumably the stock of negatives, as announced in the Hongkong Daily Press on 18th July 1865:

NOTICE. The undersigned having purchased the Photographic Establishment of Messrs. S. W. Halsey & Co., respectfully beg to inform the Public that they will continue the business of that establishment, possessing all the necessary means and materials, they are able to take Views and likenesses with all the latest improvements in an efficient and elegant style, on most reasonable terms. In soliciting a continuance of Public patronage they beg to assure the Public that all orders entrusted to them, will be carefully and promptly attended to. Duplicate Portrait and Views of all parts of China, can be had at any time.

SILVEIRA & co.

Hongkong,

5th June, 1865.

On 25th January 1866 Silveira advertised in the Hongkong Daily Press:

MESSRS. SILVEIRA & co. beg to call the attention of the Community to their late improvements in developing and fixing PHOTOGRAPHS, and they can now with perfect confidence assert that portraits taken at their establishment are equal to any by artists in Europe. Parties having Cartes de Visite, etc, taken are not expected to pay unless the portrait is thoroughly approved of.

Hongkong,

29th December, 1865.

Fig. 1.3. Silveira & Co. Studio advertisement from

the Hongkong Daily Press, 25th January 1866.

Author’s Collection.

He published a similar advertisement in the Hongkong Daily Press on 7th March 1866:

IMPROVED PHOTOGRAPHS.

MESSRS. SILVEIRA & co. beg to call the attention of the Community to their late improvements in developing and fixing PHOTOGRAPHS, and they can now with perfect confidence assert that portraits taken at their establishment are equal to any by the best European artists.

Parties having Cartes de Visite, etc, taken are not required to pay for them unless they quite approve of the picture.

A large stock of Apparatus and Chemicals at moderate prices, always on hand; also Views of Hongkong, Canton, Macao, and Various others of North China.

Hongkong,

6th February, 1866.

Little more is known about the Silveira studio. There is a brief mention in the Hongkong Mercury on 8th August 1866 that Silveira & Co. had taken photographs of condemned pirates. The China Mail published a report of the laying of the foundation stone of the Hong Kong City Hall on 23rd February 1867 (reprinted in the London and China Telegraph, 5th April 1867, p. 182), at which Silveira photographed the governor and his guests:

At this stage of the proceedings Mr. Silveira, the photographer, made himself observable with camera and prepared plate, hitting off the group upon the platform in a couple of seconds; and the company adjourned to the refreshment room, where, we are informed, about forty sat down to tiffin, and congratulatory addresses were interchanged.

Fig. 1.4. Silveira & Co. Western child being held

from behind, c.1865–67. Hand-coloured

albumen-print carte de visite. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.5. Silveira & Co. Reverse of fig. 1.4.

Author’s Collection.

In early 1867 Silveira sold out to the Englishman, William Floyd, who had for a short time been his assistant, but he continued to work in the business until his death in February 1874. Lastly, it should be noted that Lai Afong, arguably the best Chinese photographer of the nineteenth century, at one time worked for Silveira. We know this because some of his early cartes de visite have printed on the reverse: ‘Afong, Photographer, Late of Silveira & Co. No. 54, Queen’s Road, Hongkong.’

Wiebeking, Cearns & Co. (fl. 1866)

The 1865 China Directory lists ‘E. Wiebeking, photographer, Stanley Street.’ Wiebeking subsequently formed a partnership with W. G. Cearns in early 1866. On 4th January 1866 the Hongkong Daily Press carried the announcement:

WE the undersigned beg to inform the Ladies and Gentlemen of Hongkong that we are about to open a PHOTOGRAPHIC Establishment at No. 111 Queen’s Road Central, and being the only European Photographers in the Colony, we most respectfully solicit their patronage.

The Business to be conducted entirely on European principals [sic].

Due Notice will be given of our day of opening.

Messrs. WIEBEKING, CEARNS & CO., &c., &c., &c.

Hongkong,

28th December, 1865.

The otherwise unknown Edward A. Wiebeking and W. G. Cearns were in partnership for just under two months. Their studio opened in early February 1866, as advertised in the Hongkong Daily Press on 2nd February 1866:

Wiebeking, Cearns and Co., Photographic Establishment. 111 Queens Road – opposite Stag Hotel – 2nd February, 1866.

However, the 26th March 1866 issue of the Hongkong Daily Press reported that the partnership had been dissolved, and that Wiebeking at 111 Queen’s Road would be responsible for any debts. Wiebeking struggled on alone, and his studio was advertised in the Hongkong Mercury & Shipping Gazette on 2nd June 1866:

E. A. WIEBEKING & CO’S

Photographic Establishment,

Open From 9 Till 5 o’Clock

Opposite the Stag Hotel, No. 111,

Queen’s Road.

But just a month later Wiebeking was clearly in financial trouble, and on 19th July the Hongkong Mercury & Shipping Gazette advertised the auctioning of his ‘2 cameras (nearly new), with chemicals, baths, glasses,’ as well as his household goods (R. Wue, E. K. Lai and J. Waley-Cohen, Picturing Hong Kong, 1997, p. 30). Wiebeking had evidently been unable to meet his rent and the following day he was adjudged a bankrupt in the Supreme Court of Hongkong (Hongkong Daily Press, 24th July 1866). All debts were to be notified to Cearns, who was by then the manager of the Stag Hotel (Hongkong Daily Press, 21st August 1866). No photographs from this studio, or by Wiebeking and Cearns as individuals, have been identified.

Marciano Antonio Baptista (1826–1896)

A talented artist, the Portuguese Marciano Baptista took lessons in Macau from the famous British painter, George Chinnery, who lived in the Portuguese colony from 1825 until his death in 1852. Some of Baptista’s watercolours have survived and can be found in the Macau Museum of Art and in the Hong Kong Museum of Art. Born in Macau, the son of a mariner, he moved to Hong Kong where he attempted to make a living as an artist. Finding little demand for his work, he switched to portrait photography and painting the backdrops for the Hong Kong Amateur Dramatic Society’s performances.

It is not known for certain when Baptista began to practise photography, but we do know that he attempted to sell his photographic equipment in 1866 because the Hongkong Mercury & Shipping Gazette announced on 11th August 1866 for sale his ‘3 cameras and lens, large and small, and requisite chemicals etc., all new almost . . . price $370.’ Baptista also offered the buyer a one month’s crash course in photography. However, the advertisement was still running when the newspaper closed down in December 1866 (R. Wue, E. K. Lai and J. Waley-Cohen, Picturing Hong Kong, 1997, p. 30, noting also Clark Worswick’s record that Baptista’s family lore held that his speciality was post-mortem photography for Chinese notables).

Baptista married Maria Josepha, probably in Macau, but by the late 1850s the couple had moved to Hong Kong where they had some eleven children. Engravings of his paintings appeared in the Illustrated London News on 28th March 1857 which recorded that they had been ‘drawn by a Portuguese named Baptista, who is here thought a clever artist and who was a pupil of Chinnery.’ A letter in the China Mail of 3rd September 1857 recommended the work of ‘Marciano Antonio Baptista, a pupil for a time of Chinnery,’ and in the same year Baptista advertised ‘views of Hong Kong, Macao, etc., after the late Mr Chinnery, as well as his own original sketches.’ (See Carl Smith’s letter in South China Morning Post, 15th June 1974; also Patrick Conner, Marciano Baptista, Martyn Gregory Gallery, Catalogue 55, 1990, and George Chinnery, 1993, pp. 280–1.)

The Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, Philippines etc. for 1869 lists ‘M. Baptista’ as the photographic printer for the China Magazine. It seems reasonable to suppose that this is Marciano although his name does not appear again in connection with the journal. Marciano Baptista died in Hong Kong in 1896. A short obituary appeared in the Hong Kong Daily Press on 19th December 1896.

William Pryor Floyd (1834–c.1900)

William Floyd had a long and distinguished photographic career in China producing work of a very high standard and operating, for a time, one of the most successful studios in the Far East. In the late 1860s Floyd was John Thomson’s major competitor in Hong Kong. Examples of his photography can be found in various collections around the world, including the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, which holds several of his albums. Although we know quite a lot about his commercial activities, we know less about his personal life and background.

Fig. 1.6. William P. Floyd. Panoramic View of Macau, c.1872–73.

Six-plate albumen-print panorama, titled and numbered in the

negatives. Author’s Collection.

Floyd was born in Phillack, Cornwall in 1834, where his parents, John Floyd (1797–1867) and Elizabeth Pryor (1800–1848), had married in July 1823. According to the 1841 Phillack census there were six children and William was the second youngest. His father owned the local tavern, surviving today as the Bucket of Blood, but then called the New Inn. John Floyd was also the principal shareholder in the schooners Maria and Betsey, working out of the nearby port of Hayle. The seventeen-year-old William Floyd was still at home when the 1851 census was taken, and he was recorded as employed as an innkeeper’s son.

We do not know what Floyd did for the next dozen years or so. The Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, Philippines etc. first refers to him in its edition for 1864 where he is listed as a photographer’s assistant working in the Shanghai studio of R. Shannon & Co. The directory gives the same listing for 1865 but in 1866 Floyd, for some reason, is listed as a resident in the treaty port of Ningpo (Ningbo), although his occupation is not shown. Floyd had in fact moved to Macau in 1865 where he opened a studio which burnt down the following year. This was reported in the Hong Kong Daily Press on 25th January 1866:

FIRE AT MACAO – We have received accounts from Macao of the destruction by fire of Mr. Floyd’s photographic establishment at that place. He says “on Friday last about 8.30 A.M. two Chinese came to my place and were conversing near the window of the waiting room on the west side of the building; shortly after one came and addressed me, the other remaining near the window as above mentioned, the former wishing to learn the business and to purchase apparatus &c. I invited him inside and had verbally agreed to prices &c. About 2.30 P.M. whilst taking a cup of coffee in the Hotel, fire broke out on the west side and near the window of the waiting room; in less than fifteen minutes the entire building was in fl ames from end to end. I ran into the burning building and saved a camera which had just caught fire a chair and a pedestal; these are all that I saved from the fire, with the exception of a few chemicals that were in the Hotel. I cannot overestimate my loss as the goods cannot be replaced in this country.”

Floyd presumably lost all of his negatives, and it seems unlikely that he was adequately insured, if at all. He did restart his Macau operation, however, and an advertisement appeared in the Hong Kong Daily Press on 25th August 1866:

PHOTOGRAPHY. The Undersigned begs to call the attention of Excursionists visiting Macao, to his well-known establishment for Unsurpassed Card Portraiture.

A Visit will confirm this assertion. Orders can be forwarded to Hongkong through an Agent, to any address, to be paid for on delivery, viz., $4 for the first dozen, or $9 for 3 dozen, including the negative, which will be forwarded with the Orders.

W. P. FLOYD,

Photographic Artist.

Praya Grande, South, Macao,

6th August, 1866.

By 1866 Macau was no longer a thriving trading port. In fact, it was seen as something of a backwater. Its main attraction, as far as Floyd was concerned, would have been that it was a popular summer venue for residents escaping the oppressive heat of Hong Kong. This explains why the above advertisement was placed in one of the colony’s newspapers: Floyd was seeking to attract to his Macau studio excursionists from Hong Kong who wished to have their portrait taken. Floyd did not however stay in Macau for much longer and in late 1866 or early 1867 he joined the Hong Kong studio of Silveira & Co. and soon became its owner, with Silveira working for him. He advertised in the China Mail on 25th March 1867:

W. P. Floyd, Photographic Artist, late operator to Messrs. Silveira and Co., establishment will be opened in a few days. No. 62 Queen’s Road Central, opposite to Bank of India, Australia and China, four doors west of late Messrs. Silveira and Co. Mar. 24.

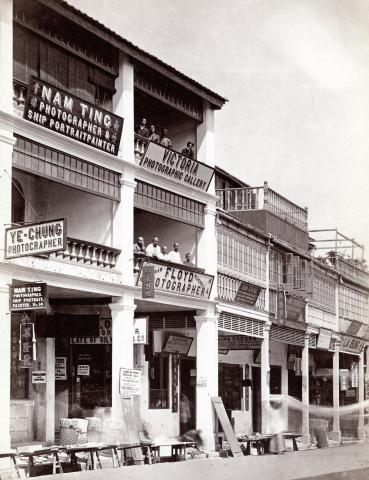

The China Mail for 2nd April 1867 advertised Floyd & Co’s ‘Victoria Photographic Gallery’ at 62 Queen’s Road Central, and on 8th May the Hong Kong Daily Press referred to its opening on 8th April.

Fig. 1.7. William P. Floyd. ‘Victoria Photographic Gallery,’ c.1867.

Floyd’s studio at 62 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong.

Royal Asiatic Society, London.

Floyd was now established in Hong Kong and at that time his only major Western rival would have been the American Weed Brothers’ studio, which had opened in March 1866 (for the Weeds, see History of Photography 1842– 1860, pp. 163–9). Amongst the steadily growing number of Chinese studios, Pun Lun would have perhaps provided the stiffest competition. And at around this time the formidable Lai Afong would have been setting up his own business.

Shortly after opening his new studio, Floyd was approached by an unnamed Chinese who wished to purchase a camera and lens, as he told Mr John Martin Armstrong of the Hong Kong merchants Thomas Hunt & Co. on 24th April 1867 (Cambridge University Library, Jardine Matheson Archive, letter 8833; ‘Mr Weed’ is presumably Charles Weed):

Sir,

Mr Weed yesterday told me that he would buy the Chemicals etc. excepting the Camera which he did not require; today a Chinese called on me to purchase a Camera and Lens I told him to come back in the afternoon when I could show him what he required. If you will kindly send me the Camera and lenses, with the lowest price (allowing a small margin as commission) I will try and sell it for you or return the same in the morning.

Respectfully, Mr W. P. Floyd.

Towards the end of 1867, Floyd appeared as a defendant at the Hong Kong Supreme Court and, as a result, some notable information about him emerges. The China Mail reported on 3rd September 1867:

W. R. Bristow v. W. P. Floyd, $82.50, for Board and Lodging. This was a balance of account contracted in November and December last year at Macao. Plaintiff keeps a private boarding-house there, and defendant was staying there for some time. Defendant, however, demurred to being charged for four days during which he was absent in Hongkong and elsewhere; he was willing to pay for 15 days, instead of 19, as charged. His Honour said he thought that it was the rule that one had to pay for board at an hotel, whether or not he lodged there. Defendant stated that he had been sixteen years in China, and his impression was different; and he refused to agree to pay $22, although plaintiff was willing thus to settle it, on the proposition of the Judge. After a very long harangue on both sides, in which “close circumstances,” “selling liquor without a license,” and other irrelevant matters were touched upon, His Honour ordered the defendant to pay $27.50. At the same time, the Judge ruled that in any case when an hotel-keeper or boarding-house-keeper had to keep a room for an absent boarder, that boarder would have to pay for the same.

The debt obviously relates to Floyd’s last days in Macau when he was presumably winding up his studio affairs before moving to Hong Kong. What is particularly interesting is his reference to having spent sixteen years in China. There is no record of his name in the earlier trade directories for China, and his movements between 1851 and 1864 remain uncertain.

Floyd continued to consolidate his position in Hong Kong. It was important that he did so because he was about to encounter some major commercial competition with the arrival in February 1868 of the ambitious and talented John Thomson (see p. 216). For the next two years Floyd and Thomson competed for dominance of the local market. That Floyd managed to survive, and even outlast Thomson’s stay in the colony, says much about his photographic ability, commercial acumen and marketing fl air. However, the price war that the two photographers embarked upon (with the Chinese studio of Pun Lun joining in) must have weakened Floyd financially. Whilst most commentators would argue that Thomson was the superior talent, it cannot be denied that Floyd presented Thomson with serious and sustained competition. Floyd did this by launching a series of local newspaper advertisements in which he displayed skill and imagination in his appeals to potential customers.

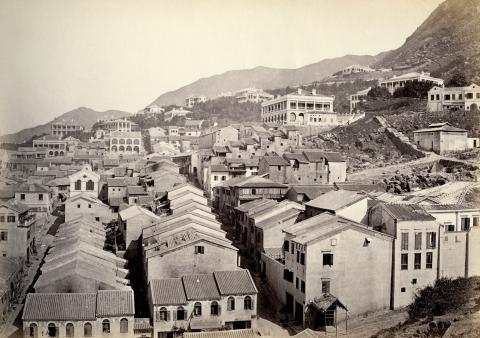

Fig. 1.8. William P. Floyd. ‘Tai Ping Shan, Hong Kong –

Chinese quarter,’ c.1868. Author’s Collection.

An advertisement in the Daily Advertiser and Shipping Gazette on 2nd April 1868 offered Floyd’s Views of China and Japan at the rates of $20 for a fifty-view album and $18 for a twenty-four-view album (this is the first indication we have that Floyd had made a photographic tour of Japan, assuming, that is, that he had not purchased the negatives from another photographer). Within a month he had reduced the prices of his albums to $18 and $12 respectively. Less than two weeks later, on 13th April 1868, the China Mail announced a new photographic process from which Floyd could produce ‘first class’ card portraits that were ‘permanent’ and ‘unsurpassed for quality by any photographer in China.’ By May 1868 the two photographers were at the height of their price war. On 22nd May 1868, the following advertisement appeared in the China Mail:

PHOTOGRAPHIC VIEWS OF HONG KONG, &c., &c.

MESSRS. FLOYD & CO. are now publishing a series of Views of Hongkong, Macao, Canton, Amoy, Swatow and Foochow, in two parts. These photographs are produced by new Optical Instruments, by the best Opticians of the day, and include an angle of 100 degrees, or three times the amount of subject of the ordinary lenses now in use in the East, hence the unnecessary joining to make a complete picture. We intend to reduce the price to about 50 per cent. (to Subscribers only) from our usual selling prices.

Gentlemen wishing to subscribe will please call at our Establishment, where the Photographs can be inspected and further particulars ascertained.

Hongkong,

21st May, 1868.

This advertisement must have made uncomfortable reading for Thomson and Floyd’s other competitors. Floyd was offering an attractively wide geographical range of Chinese photographs, introducing new wide-angle camera-lens technology (a Dallmeyer and Ross lens), seeking to lock-in customers on a subscription basis and simultaneously reducing his prices by fifty per cent. The photographs in question were favourably reviewed in the China Mail on 23rd May 1868.

Floyd continued his energetic marketing campaign in the China Mail. On 22nd June 1868 he placed a combative advertisement headed: ‘Opposition is the Life of Trade!!!’ and Floyd & Co’s Victoria Photographic Gallery announced a price reduction on cartes de visite from five dollars to three dollars a dozen. Two more favourable reviews appeared, one, on 22nd July 1868, in the Hong Kong Daily Press, the other, on 8th August 1868, in the China Mail (the latter is reprinted in Appendix 4). In response to Thomson’s announcement of a lowering of prices in September, Floyd issued a counter-advertisement, dated 21st September 1868, which was printed in the Hong Kong Daily Press on 21st October 1868 (and presumably in earlier issues):

NOTICE.

NOW Publishing, a series of Photographic Views of Hongkong, Canton, and Macao, Characteristic Groups, &c., &c., by the undersigned. About 150 Photographs to select from.

In sets of 50 mounted, price $30.00

'' ½ '' 25 '' '' 20.00

50 unmounted, '' 25.00

'' ½ '' 25 '' '' 15.00

FLOYD & Co.

Hongkong,

21st September, 1868.

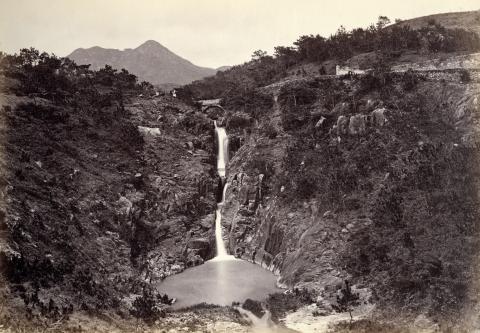

Fig. 1.9. William P. Floyd. ‘Water Fall & The Bridge, East Point,’

c.1868. Numbered ‘71’ in the caption. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.10. William P. Floyd. ‘Waterfall Bay, Hong Kong,’ c.1868.

Author’s Collection.

The next few months saw a flurry of advertisements and then Floyd announced that he would move his studio from 62 Queen’s Road Central to a corner site at Wyndham and Wellington Streets, as advertised in the China Mail on 25th May 1869:

NOTICE.

THE Undersigned begs to inform his Patrons, that his GALLERY will be closed 1st June for taking Card Photographs, consequent on his Removal to the New Establishment, on the corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets, opposite ATICK, Tailor.

Ordinary business will be conducted during the month of June, in the new Establishment.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

24th May, 1869.

Demonstrating that Floyd was not without connections in the colony, he was able to announce in an advertisement, dated 9th August 1869, printed in the Hong Kong Daily Press on 13th May 1870 (and no doubt earlier issues) that the Governor of Hong Kong himself would be opening his gallery:

UNDER the Distinguished Patronage of His Excellency, The Governor and Lady MacDonnell,

MR W. P. FLOYD

Begs to announce that his Photographic Gallery has been RE-OPENED by His Excellency Sir R. G. MacDonnell, C.B., and Lady MacDonnell, on the Corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets, where he solicits an inspection of the Finest Photographic Establishment in the Far East.

Life Size Photographic Portraits, in Oil or Water Colors.

Hongkong,

9th August, 1869.

Fig. 1.11. William P. Floyd. ‘Melchers & Co’s House,’ Hong Kong,

c.1868. Signed in the negative and numbered ‘11’ on the

photographer’s printed label. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.12. William P. Floyd. ‘The Union Chapel,’ Hong Kong, c.1868. Numbered ‘23’ in the negative. Author’s Collection.

In the 1870 edition of the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, Philippines etc. Floyd is still listed at the above address with José Silveira, the former owner of the gallery, in his employment. The Colonial Office records indicate that at this time Floyd’s family in England had become concerned about his welfare, not having heard from him for some time (National Archives, Kew, ref.: CO 129/146). They had apparently approached John St Aubyn, MP for West Cornwall, for help, and on 16th August 1870 he had written to the Earl of Kimberley, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to enquire after William on their behalf. Kimberley in turn wrote to the Governor’s office in Hong Kong and received this reply, dated 6th October 1870, from the Lieutenant Governor, Major General H. W. Whitfield:

My Lord,

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of Your Lordship’s Despatch of the 19th August, No. 20, making enquiries at the instance of Mr. St. Aubyn, M.P. for West Cornwall, respecting Mr. William Pryor Floyd. In reply I have the honour to acquaint Your Lordship that Mr. Floyd is doing an excellent business in the Colony as a Photographer, and that he has of late made amends for long silence by writing to his family.

I have the honour to be, My Lord,

Your Lordship’s most obedient humble servant,

H. W. Whitfield.

On 29th October 1870, Floyd was again reducing his charges. The earliest documentation of this that has been found is an advertisement published in the China Mail on 25th May 1871:

PHOTOGRAPHY.

REDUCED PRICE LIST.

Cartes de Visite, vigts. 3 doz. $7.00.

Do. Full length 3 doz. 6.00.

Do. of Children, per doz. 5.00.

Views of Hongkong, etc., price list on application. The most permanent Photographs extant.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

29th October, 1870.

Floyd also embarked on a series of raffles of his photographs: the sixth (December 1870) was advertised in the China Mail on 17th November 1870, the ninth (December 1873) on 22nd November 1873 (R. Wue, E. K. Lai and J. Waley-Cohen, Picturing Hong Kong, 1997, p. 56, n.38). The most likely explanation for this sales tactic is growing commercial pressures on his studio, rather than a successful marketing ploy. Floyd, therefore, is likely to have been thinking about his exit strategy at this time and a year later he announced the sale of his business in the China Mail, 11th December 1871:

PHOTOGRAPHIC BUSINESS.

FOR SALE.

THE GOODWILL and stock-in-trade of the Largest Photographic Establishment in the East; consisting of CAMERAS of all sizes and for every purpose. LENSES for Views, PORTRAITS and GROUPS, by Ross, Dallmeyer and Harrison, together with FURNITURE, and every requisite connected with a First Class Establishment, including several thousands of NEGATIVES.

For Further particulars, apply to

W. P. FLOYD, Wyndham & Wellington Sts., Hongkong.

11th December, 1871.

We should probably take Floyd’s claim that his was the ‘Largest Photographic Establishment in the East’ at face value. In his 9th August 1869 advertisement he claimed the patronage of the Governor at ‘the Finest Photographic Establishment in the Far East,’ while in October 1870 the Lieutenant Governor had reported that Floyd was ‘doing an excellent business in the Colony as a Photographer.’ Floyd had enjoyed, at least for some years, considerable success as a photographer in Hong Kong. Now, aged thirty-seven, he was attempting to retire, at least from the photographic portrait market. The China Mail carried the following announcement on 12th February 1872:

PHOTOGRAPHY – CLOSING OF BUSINESS.

The Undersigned begs to inform his Numerous Patrons that his Business (for Portraiture) will be CLOSED on and after the 1st May next. Ladies and Gentlemen wishing Copies from their negatives taken previous to this date can be supplied with Three Dozen for $5, including all their Negatives, which will be sent with the order.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

12th February, 1872.

Perhaps Floyd contemplated an ongoing business in which he sold scenic views of China, rather than continuing in the increasingly competitive world of portrait photography, especially as Chinese studios were by then enjoying success with the local foreign residents. In any case on 29th April 1872 the China Mail announced a month’s postponement of the closure:

CLOSING OF BUSINESS.

Three dozen Carte de Visites $5

FROM May 1st to 31st, the above REDUCED PRICE will be charged, including taking the negative. The Establishment will be positively CLOSED on June 1st for Portraiture.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

29th April, 1872.

Fig. 1.13. William P. Floyd. Chinese lady, c.1872.

Albumen-print carte de visite. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.14. William P. Floyd. Reverse of fig. 1.13.

Fig. 1.15. William P. Floyd. ‘Chinese Crockery Mender,

Hong Kong China, 1868.’ Albumen-print carte de visite.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.16. William P. Floyd. Reverse of fig. 1.15.

Consistent with his apparent aim of exiting from portrait work the Hong Kong Daily Press on 27th June 1872 advertised an auction of the contents of Floyd’s household and portrait studio:

AUCTION – FURNITURE SALE.

LANE, CRAWFORD & CO. have received instructions to sell by Public Auction, at the Victoria Photographic Rooms, Wyndham Street, the whole of the HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE of W. P. Floyd Esq., THIS DAY, the 27th June 1872, at noon, – Consisting of Damask Covered CHAIRS and COUCHES, Side TABLES, PIANO, HARMONIUM, MIRRORS, ENGRAVINGS, window CURTAINS, CARPET, dining TABLE, SIDEBOARD, CROCKERY, and glassware, BEDSTEAD, WARDROBE, WASHSTANDS.

Also,

A quantity of Photographic Apparatus &c. &c. &c.

Catalogues will be issued.

TERMS OF SALE: – Cash before delivery in Mexican Dollars weighed at 7.1.7. All Lots, with all faults and errors of description, at purchasers’ risk on the fall of the hammer.

Hongkong,

20th June, 1872.

Following completion of the auction, the China Mail on 2nd July 1872 indicated the new occupants:

NOTICE OF REMOVAL.

THE HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS,

have this day been REMOVED to the Premises lately occupied by W. P. FLOYD, at the corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets.

OPEN EVERY DAY FROM 10 A.M. TO 3 P.M.

E. RUSFELDT.

Hongkong,

2nd July, 1872.

The China Mail of 3rd September 1872 is revealing of Floyd’s plans:

PHOTOGRAPHY.

MR. FLOYD begs to announce to his numerous Patrons, that he is now publishing a new set of Photographs of the South of China, and will publish a Series of Views of Japan in November next.

Ladies and Gentlemen requiring Copies from their negatives can be supplied on application at Wyndham Street, next door to the (late) gymnasium.

-----------------------------------------------

NOTICE. DURING my temporary absence from the Colony, Mr. J. J. A. DA SILVEIRA will act for me in my name and conduct my BUSINESS generally.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

2nd September, 1872.

Fig. 1.17. William P. Floyd. Chinese lady, c.1870.

Albumen-print carte de visite. Author’s Collection.

It now seems clear that Floyd has divested himself of his portrait studio but retained (presumably having failed to sell) the negatives from which he is happy to take prints for past customers. His concentration, however, now seems to be on views of China and Japan and he plans to sell these from his new gallery. Presumably he now travelled to Japan to secure a fresh series of views. On his return, the China Mail announced on 13th November 1872 the opening of his new gallery:

PHOTOGRAPHY.

MR FLOYD’S NEW PHOTOGRAPHIC GALLERY

will be Opened on THURSDAY, 14th inst.

Wyndham Street, next door to the GYMNASIUM.

Hongkong,

11th November, 1872.

Being clearly still active on the Hong Kong photography market, Floyd was anxious to dispel a notion that he had sold out to E. Rusfeldt (Riisfeldt). The following, printed in the China Mail on 30th November 1872, made matters clear:

REFUTATION.

It having come to my knowledge that many persons in this colony are under the impression that I sold my Business and Good-will to Mr. E. RUSFELDT – I beg to contradict that calumny.

W. P. FLOYD.

Hongkong,

29th November, 1872.

-----------------------------------------

In reference to the above, I beg to state that Mr. FLOYD did not sell the Goodwill of his Business to me; he merely left the house to me without compensation.

E. RUSFELDT.

Hongkong,

29th November, 1872.

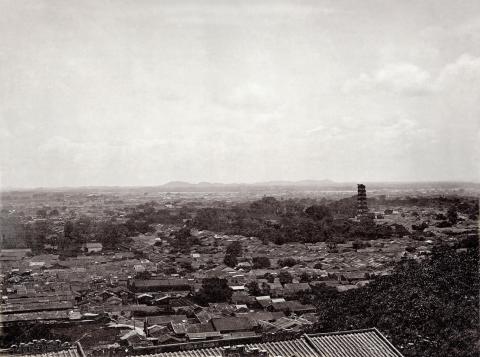

Fig. 1.18. William P. Floyd. ‘General View of Canton,’ c.1870.

Numbered ‘33’ on the photographer’s printed label.

Author’s Collection.

The 1873 Hong Kong Jury List (Hong Kong Public Record Office) lists José Silveira as an assistant to Floyd & Co. at Wyndham Street and the China Directory for 1873 gives the old gallery name of ‘Victoria Photographic Gallery.’ In that year Floyd issued his ‘Floyd’s South China Album, Hong Kong, 1873.’ (One of these albums was sold at Christie’s, London on 27th October 1983, lot 142; inscribed 2nd June 1873, it contained fifty photographs; eight images were of Japan.) On 22nd November 1873 the China Mail announced Floyd’s ninth raffle. The China Directory for 1874 gives Floyd’s address as Wellington Street, which suggests he may have moved. His last significant photographic publication in Hong Kong occurred in September 1874 when he issued twenty two photographs of the recent typhoon which had devastated much of the colony (a copy of this album is held by the University of Michigan Library).

Floyd now decided to leave Hong Kong and head for the Philippines where he established a new studio. Gonzalez and Moreno’s directory, Anuario Filipino for 1875 and 1877 listed Floyd (misspelling him first as ‘Floyel’, then as ‘Floid’) as a photographer at the same address in Manila, 49 (Calle) Sto. Cristo, segunda (with acknowledgment to Mike Price for this reference). It is not clear how long Floyd stayed in the Philippines. It is surprising that a ‘W. P. Floyd’ is recorded as having a dark room in Hong Kong in 1898 by Henry Sturmey, ed., Photography Annual for 1898. Assuming, as seems likely, that this is our William Floyd, he would then have been aged sixtyfour. Lastly, it is worth noting two ships’ passenger listings, both printed in the Homeward Mail: one, for 21st October 1905, names a ‘W. Floyd’ on the SS Victoria, due to leave for the Far East on the 27th of that month, the other, for 4th January 1913, has a ‘W. Floyd’ on the SS Egypt, due to leave London on the 17th for Port Said.

William Floyd’s final years may be shrouded in mystery, but his time in China established him as one of the finest photographers in the Far East in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

Fig. 1.19. William P. Floyd. Chinese lady, c.1870.

C. von der Burg Collection.

Fig. 1.20. William P. Floyd. ‘Five Storied Pagoda, And Old Fort,

Canton,’ c.1870. Numbered ‘34’ on the photographer’s printed label.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.21. William P. Floyd. ‘Mahommedan Minaret, Canton,’ c.1870.

Numbered ‘32’ on the photographer’s printed label. Author’s Collection.

Hongkong Photographic Rooms and Emil Riisfeldt (1846–1893)

Emil Riisfeldt’s surname was frequently rendered as ‘Rusfeldt’ or ‘Rüsfeldt’ in advertisements placed in Hong Kong, but in his subsequent photographic career in Australia he invariably used the correct spelling, Riisfeldt. This will be used here except in quoted material.

We first hear of the Hongkong Photographic Rooms in an advertisement placed in the China Mail on 19th April 1872:

THE HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS

(Corner of Wellington & d’Aguilar Streets)

ARE NOW OPEN

from 10 A.M. to 4 P.M.

Portraits taken in any Weather. N.B.

The Photographic Rooms, are over the Daily Advertiser Office.

E. RUSFELDT.

Hongkong,

18th April, 1872.

In the China Mail of 2nd July 1872 we learn that the proprietor of the studio, ‘E. Rusfeldt’ has relocated to William Floyd’s late studio premises:

NOTICE OF REMOVAL.

THE HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS,

have this day been REMOVED to the Premises lately occupied by W. P. FLOYD, at the corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets.

OPEN EVERY DAY FROM 10 A.M. TO 3 P.M.

E. RUSFELDT.

Hongkong,

2nd July, 1872.

It will be remembered that William Floyd owned the ‘Largest Photographic Establishment in the East’ and had announced the closure of his photographic portrait business on 1st June 1872 (see p. 14). On 27th June he auctioned off the contents of his studio and it is possible that Riisfeldt was the successful bidder for some or all of the items offered. He must at least have entered into some financial arrangement, since he took over Floyd’s premises and substituted the Hongkong Photographic Rooms name for the existing Victoria Photographic Rooms. It would be rash to assume, however, that Riisfeldt acquired the previous incumbent’s negatives since Floyd continued to operate, certainly in landscape photography, from a nearby location. Also, only a handful of prints have so far been attributed to Riisfeldt and, as far as can be established, none of them has yet been shown to have been struck from original Floyd negatives. Finally, Floyd felt compelled on 29th November 1872 to issue a notice in the local press refuting the notion that he had sold his business to Riisfeldt, confirming instead that the latter had simply moved into his previous premises (see p. 17).

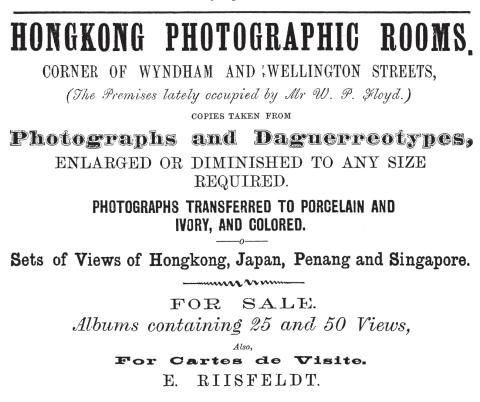

Riisfeldt placed an advertisement in the 1873 edition of the China Directory, detailing the types of photographs and services on offer. He was not only operating a portrait studio, but also offering a portfolio of views not restricted to Hong Kong.

The earliest known advertisement to mention Emil Riisfeldt in Hong Kong is found in the China Mail on 18th October 1871:

AFONG

PHOTOGRAPHER

54 QUEEN’S ROAD, HONGKONG

INVITES Inspection of his large collection of views FOOCHOW, HONGKONG, CANTON, SWATOW and MACAO.

The Proprietor begs to say that he has entered into an engagement with a very able Artist, EMIL RUSFELDT, by whom Portraits will be effectively taken.

Hongkong,

18th October, 1871.

By April 1872 Riisfeldt had left Afong’s employment to open up his own studio, as we saw from the advertisement he placed in the China Mail on 19th April. On 24th July 1872 the same newspaper carried the following:

HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS

orner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets

(The premises lately occupied by Mr. W. P. FLOYD)

Copies taken from PHOTOGRAPHS and DAGUERREOTYPES, enlarged or diminished to any size REQUIRED.

PHOTOGRAPHS TRANSFERRED TO PORCELAIN AND EBONY AND COLOURED.

VIEWS FOR SALE.

E. RUSFELDT

Hongkong,

23rd July, 1872.

The next day, 25th July, the China Mail printed another advertisement:

NOTICE.

THE GROUPS taken on the 17th inst. at Government House, and on the 18th instant at Head-Quarter House, are now ready for inspection, and Copies thereof may be had on application to the Undersigned. Also, Portraits in different sizes, of his Majesty the King of Cambodia.

E. RUSFELDT,

Hongkong Photographic Rooms,

Corner of Wyndham and Wellington St.

Hongkong,

22nd July, 1872.

And in the China Mail for 29th November 1872:

NOTICE.

E. RUSFELDT’S First Grand Gift Enterprise of PHOTOGRAPHS, VIEWS, &c., for CHRISTMAS PRESENTS, will take place on December 19th, at 4 P.M. All Prizes $5 per number. Further particulars on application at the HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS, corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets.

Hongkong,

28th November, 1872.

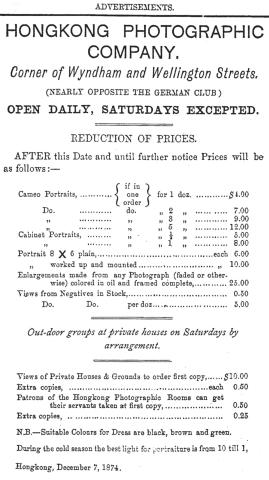

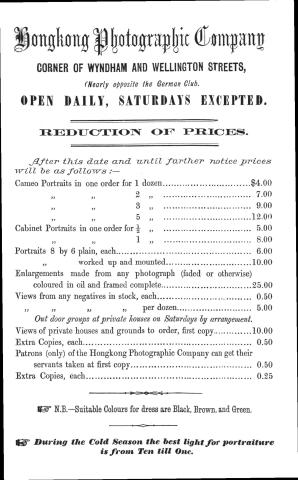

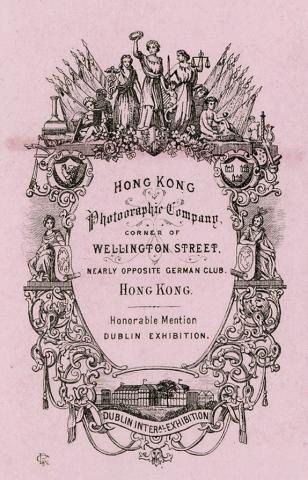

Fig. 1.22. Hongkong Photographic Rooms. Advertisement for

the Hongkong Photographic Rooms from the China Directory, 1873.

Author’s Collection.

Riisfeldt’s studio in Hong Kong continued to operate until late 1873, after which the business passed to the Hongkong Photographic Company and Riisfeldt headed for Australia.

Emil Riisfeldt was born in Helsingør, Frederiksborg, Denmark on 29th April 1846 (he was christened Peter Emil Thorwald but he was known as Emil). The Danish census records indicate that he had two brothers, Christian Wilhelm Alfred (1849–1932), known as Alfred, and Christian Henrik Riisfeldt (1853–?). The 1855 Helsingør census shows all three brothers living with their parents, Jørgen and Frederike. Nothing is currently known of Emil’s childhood, but photo-researcher Sandy Barrie has tracked down Australian descendants who tell him that Emil and his brother, Alfred, travelled the world together in the late 1860s or early 1870s before settling in Australia (with grateful acknowledgment to Sandy Barrie for this information, and also to Ole Madsen and Marcel Safier for tracing Danish genealogical data).

By October 1871 Emil Riisfeldt was in Hong Kong, as we have seen, working for the experienced Chinese photographer, Afong, who described him as ‘a very able Artist.’ It is very likely, therefore, that Riisfeldt had practised photography before arriving in Hong Kong. References to ‘Sets of Views of Hongkong, Japan, Penang and Singapore’ in advertisements placed in the 1873 editions of the Chronicle and Directory for China and the China Directory at least suggest that he may have photographed in the places mentioned prior to opening his studio in Hong Kong.

On leaving Hong Kong Riisfeldt headed for Australia. In December 1873 he is listed as a passenger on the Christianshaven sailing from Melbourne to Sydney, where, a year later, he married Emma Pyle. The couple had two children: Alfred (1875–1876) and Caroline (1880–c.1956) (information kindly supplied by Marcel Safier). Emil’s brother, Alfred, arrived in Sydney on the Cambridgeshire in 1875. Some time in 1874 Emil opened a studio in Melbourne, at 122 Bourke Street East, but by 1876 he was settled in Sydney where he operated a succession of studios at various addresses (see Sands’s Sydney Directory and Sandy Barrie, Australians behind the Camera, 2002, p. 160). Riisfeldt also exhibited at the Calcutta International Exhibition, 1883–1884.

Emil Riisfeldt died at Newtown, New South Wales in 1893. In 1930 his unmarried daughter, Caroline, is shown in the electoral roll for Sydney working as a music teacher and living with her mother who died that year. Although there are unlikely to be any direct descendants of Emil, his brother Alfred, who lived until 1932, had a larger family and Sandy Barrie has spoken to some descendants who indicated that Emil Riisfeldt lived extravagantly and died leaving his family in debt.So few photographs have so far been attributed to Emil Riisfeldt that it is difficult to make any judgment about his work. In fact, the author believes that existing attributions of Riisfeldt’s work should be treated with some caution. His time in Hong Kong seems to have been limited to around two years and the fate of his negatives is unknown. However, a number of portraits taken by Riisfeldt in Australia have found their way into private and public collections. Several of his Hong Kong prints are credited in the exhibition catalogue of Horstmann & Godfrey Ltd, Old Photographs of Chinese Cities (1995).

Fig. 1.23. Hongkong Photographic Rooms.

The studio premises in Hong Kong, c.1872–73.

Author’s Collection.

Hongkong Photographic Company, Ernest Wassell and Henry Everitt (1827–?)

Before leaving for Australia, Emil Riisfeldt sold his business to an unnamed proprietor who changed the name of the studio from the Hongkong Photographic Rooms to the Hongkong Photographic Company. This minor alteration of name is an indication that the new owners wished to benefit from the goodwill accumulated by Riisfeldt during his relatively short sojourn in Hong Kong. A notice duly appeared in the Hongkong Daily Press on 17th January 1874:

THE HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC COMPANY

Will commence business at the HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS, Corner of Wyndham & Wellington Sts., (Nearly opposite the German Club) shortly after the S.S. ‘GLENARTNEY.’

--------------------------------------------

The services of Mr. Henry Everitt (of honourable mention at the Dublin Exhibition) have been secured, and specimens of his Work will be offered for public inspection as soon after his arrival as possible.

Hongkong,

17th January, 1874.

Everitt would stay with the company three years until his impending departure was announced in the Hongkong Daily Press on 2nd January 1877:

HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC ROOMS,

CORNER OF WYNDHAM AND WELLINGTON STREETS,

And nearly opposite the German Club,

INTENDING SITTERS who would prefer to avail themselves of Mr. EVERITT’S SERVICE before he leaves the Colony, are respectfully informed that his engagement with us expires shortly.

HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC CO.

Hongkong,

2nd January, 1877.

Following Everitt’s departure, the premises were taken over by Ernest Wassell, who is noted in the Chronicle & Directory for China for 1877 as an assistant at the Hongkong Photographic Company. An announcement published in the China Mail on 3rd March 1877 makes the change of occupier of the Rooms clear:

ERNEST WASSELL & CO.,

PHOTOGRAPHERS

I HAVE This Day Established myself as PHOTOGRAPHER at the Corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets, at the Building lately occupied by the HONGKONG PHOTOGRAPHIC CO. under the above style.

ERNEST WASSELL.

Hongkong,

3rd March, 1877.

No further information has been found about Ernest Wassell whose career as a photographer in Hong Kong seems to have been short-lived. The author is grateful to Edwin Lai for sending the above advertisement and for sharing his notes on many of the early Hong Kong studios. Future researchers might like to note a possible relation, John Gordon Talbot Wassell, who joined the Perserverance Lodge, Hong Kong on 16th November 1869, aged twenty-four.

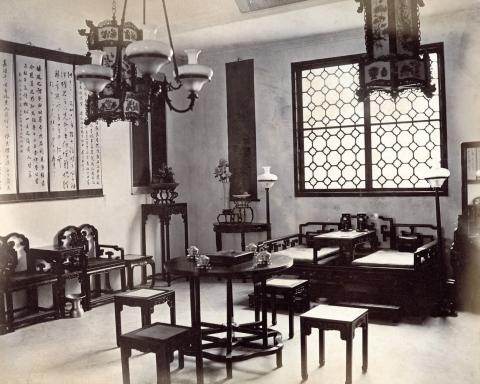

Fig. 1.24. Attributed to Hongkong Photographic Rooms.

‘Chinese Drawing Room,’ c.1872–73.

Author’s Collection.

If the ownership of the Hongkong Photographic Company remains uncertain, it is clear that its principal photographer during its three years’ existence was Henry John Everitt.

Everitt was born in Islington, London on 25th November 1827; his father, John was a coachmaster (see St Luke, Old Street, Supplementary Baptism Register, P76/LUK/017, October 1822–March 1841). In 1849 he was working as a clerk in a district post office and married Susan Jewell. He was married under the name John Henry Everitt and throughout his life he seems to have alternated his Christian names, making it difficult at times to trace his movements. On the 11th May 1857 his second son, Walter William Everitt (1857–1911), destined himself to become a photographer and noted artist, was born. By this time Henry was working as a photographer.

The 1861 census shows Henry living with his wife and son in Coventry, but in 1863 he was in London in partnership with Thomas Charles Turner, in Islington. The partnership, Turner & Everitt, moved to Cheapside in 1865, when it also exhibited a ‘frame containing twenty untouched cartes-de-visite, by the wet process, iron developed’ and won an ‘honorable mention’ at the Dublin International Exhibition. The partnership was dissolved in December 1865. Henry Everitt then operated his own studio at the Cheapside address from 1867 until the end of 1873 (see London Gazette, 1866, and Michael Pritchard, Directory of London Photographers 1841–1908, 1994, pp. 59, 112; the author is grateful to Michael Pritchard for information on Turner & Everitt). The 1871 census shows Everitt living in London with his wife and two sons. By early 1874 he had moved to Hong Kong, from where a report of his work was received and printed in the London and China Telegraph on 13th April 1874 (p. 256):

An effort is being made by Mr. Everitt, of the Hong Kong Photographic Company, to photograph the remarkable series of pictures now in the City Hall Museum, illustrative of the ten Buddhist Hells. It is not certain that their strong and gaudy colours will bear reproduction by photography, but, if successful, the effort will give students of Chinese life an interesting set of illustrations. It is, we believe, proposed to issue them with short letter press descriptions.

We lose track of Everitt after he left Hong Kong in 1877. The 1881 England census shows his wife, Susan, living with her son, Walter and her daughter-in-law in London. Perhaps Henry was no longer alive, but the 1891 census records Susan as married. A short announcement of the death of Henry’s son, Walter Everitt appeared in the British Journal of Photography on 3rd November 1911: ‘Mr. Walter Everitt was the son of Henry Everitt, who, first in “The London School of Photography,” in Fenchurch Street, and then in Cheapside, in the firm of Turner and Everitt, made a great name in London when professional photography was in its infancy’ (corrections to the studio names of the places in which Henry Everitt worked were published in the British Journal of Photography, 17th November 1911, p. 885).

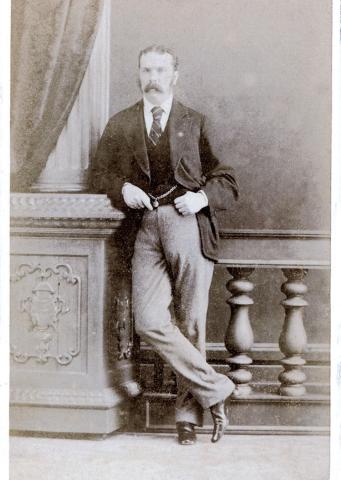

Fig. 1.25. Hongkong Photographic Rooms.

Unknown Westerner, c.1872–73. Albumen-print

carte de visite. Author’s Collection.

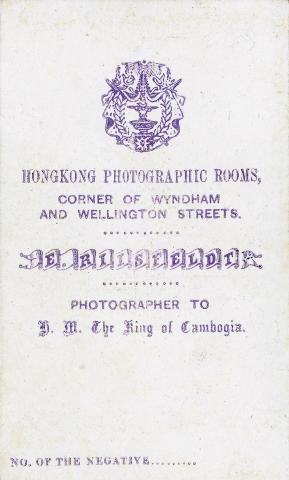

Fig. 1.26. Hongkong Photographic Rooms.

Reverse of fig. 1.25.

Henry Schüren and F. Poppelbaum

Henry Schüren moved into the premises previously occupied by Afong after the latter had moved his studio to Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong, according to an announcement in the China Mail on 29th April 1878. Schüren was still there in 1879 after which his studio was taken over by F. Poppelbaum. Schüren had worked as a photographer in the Far East for some years before he arrived in Hong Kong, at Batavia (Jakarta) in the studio of Woodbury & Page in the early 1870s, in Singapore between 1873 and 1876, visiting Siam (Thailand) in 1874 and Manila in 1875, and then moving to Bangkok. Further information on Schüren’s early career can be found in John Falconer’s A Vision of the Past (1987, pp. 25–6, 191). None of Schüren’s Hong Kong photographs have been identified, but the author has seen one from Poppelbaum’s studio, with ‘F. Poppelbaum. Photographer. Formerly H. Schüren. Hongkong’ printed on the reverse of the mount.

Fig. 1.27. Hongkong Photographic Company.

Advertisement for the Hongkong Photographic Company

from the China Directory, 1875. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.28. Hongkong Photographic Company.

Advertisement for the Hongkong Photographic Company

from the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan,

Philippines etc., 1875. Author’s Collection.

The Firm

‘The Firm’ was a term coined by Clark Worswick in his pioneering study, Imperial China: Photographs 1850–1912 (1978). It was, explained Worswick, ‘not an actual commercial entity but rather a huge collection of negatives left behind by all the photographers who had ever arrived in Hong Kong, set up shop, and then gone bankrupt. In time, The Firm would come to include the stockpiles of eleven photographic establishments that attempted to do business in Hong Kong from 1860 to 1877. As succeeding photographers went out of business, their stock would be assumed by the next professional photographer who believed that he alone knew the secret of establishing a solid clientele in South China’ (p. 139). With the departure of Henry Everitt and the closure of the Hongkong Photographic Company in 1877, Worswick considered that ‘The Firm’s history came to an end and the disposition of all its negatives remains a matter for conjecture’ (p. 142; in his note 22 Worswick thought it ‘almost certain’ that the Chinese photographer Afong ‘bought the contents of The Firm’).

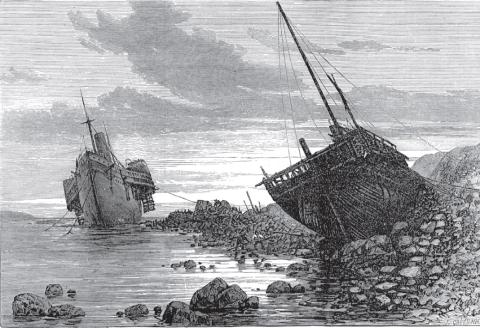

Fig. 1.29. Hongkong Photographic Company.

‘The Late Typhoon At Hongkong.’ Wood-engraving

after a photograph, from the Illustrated London News,

21st November 1874. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.30. Hongkong Photographic Company.

‘The Pacific Mail Steam-Ship Company’s Steamer

Alaska Cast Ashore.’ Wood-engraving after a photograph,

from the Illustrated London News, 21st November 1874.

Author’s Collection.

The succession of ‘The Firm’ began with the negatives of Weed & Howard, who established their studio in 1860. Their stock passed and was added to by their former assistant Milton Miller. The negatives of all three photographers were acquired by S. W. Halsey when Miller sold his business and stock to him in 1864. Halsey in turn passed them on to José Silveira, whose business was bought by William Floyd in 1867. Floyd was certainly not averse to printing from other studios’ negatives, as the China Mail remarked in 1868: ‘Two or three of those now published, are we observe by another photographic artist from whom Mr. Floyd has obtained the negatives’ (see Appendix 4). It is, therefore, possible that Floyd took possession of The Firm’s negatives as well as Silveira’s business in 1867. However, it is equally likely that they were sold off at auction and dispersed amongst more than one studio at this point and Floyd simply acquired (or retained) a selection rather than the entire stock (from an inspection of a reasonable number of albums, the author believes that Floyd did not generally include the work of others in his portfolio). What became of Floyd’s negatives after his departure from Hong Kong in 1874 remains uncertain, but it is clear that The Firm’s stock as a coherent collection had fragmented by this time and while there may have been additions to the pool of negatives in circulation they did not remain in single ownership (for example, John Thomson, Floyd’s principal competitor since 1868, left Hong Kong in 1872 with his negatives, apart, possibly, from a number, no longer required, that he disposed of locally). The concept of the ‘The Firm’ is, then, less useful in describing the nature of the photographic business in Hong Kong after 1867. The market was now sufficiently developed to accommodate more than one studio and the negatives of earlier studios were lost, discarded or merged among the portfolios of several studios.

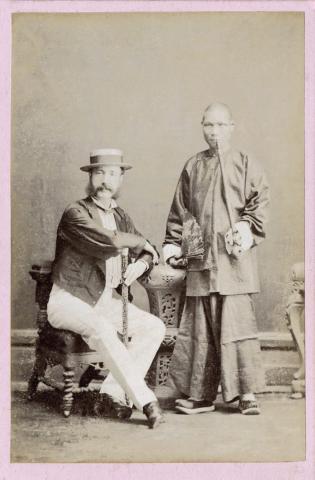

Fig. 1.31. Hongkong Photographic Company.

Western man with cane and Chinese man with

fan and pipe, c.1874–77. Albumen-print carte

de visite. The photographer is likely to have been

Henry Everitt. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 1.32. Hongkong Photographic Company.

Reverse of fig. 1.31. Note the reference to the

1865 Dublin International Exhibition in which the

Company’s principal photographer, Henry Everitt,

participated. Author’s Collection.

Early Photographers - Floyd and Thomson

An article here on Page 4 on Views of Hong Kong by early photographers, Floyd and Thomson. On Page 5 are their advertisements/notifications of publication of photographs. HK Daily Press 17 September 1868 refers (the newsprint is somewhat difficult to read)

Arrival of John Thomson in February 1868

In the Hong Kong Daily Press 1868-02-06 an advert appears:

Mr. John Thomson, photographer, begs to intimate that he will visit Hong Kong by the next French Mail. Saigon, 26th January 1868.