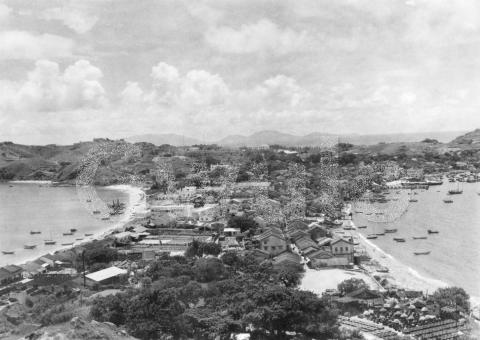

This week's photo comes from the same set as last week's "Shinrock Hotel" photo. The printer's bad spell must have passed, as this photo is correctly titled:

WHOLE VIEW OF CHEUNG CHOW

The photographer was standing on the slopes at the northern end of the island, looking south across the built-up centre towards the hills at the southern end.

Like last week's photo, this one needed a bit of tweaking to sort out the poor printing, but the underlying photo is good and sharp.

Down in the bottom-right corner there is an assortment of trays laid out in the sun, and lines of what look like barrels and umbrellas.

My first guess in an island photo like this is that we're looking at the production of shrimp paste, like we still see at Tai O today. However we've previously seen this area in a photo from the 1930s, and that had another explanation. Here's the photo. This time the photographer was on the southern hills looking north, so it's a view in the opposite direction to the 1950s view:

Here's a close-up of the hillside above the trays & barrels area:

Ford Wong wrote in to explain what we're looking at:

The terraces are part of a preserved fruit factory, Wong Wing Kee Preserved Fruit Factory, which dated back to 1908. In those days, the workers use the sun light to dry the fruit and made over 30 varieties of products.

The factory moved to China in the 1970's when the labour source dried out.

So I guess the 1950s photo shows fruit too, but corrections welcome.

|

Gwulo.com - Powered by Patrons Gwulo's patrons make a regular contribution towards the costs of running Gwulo.com If you value Gwulo's website & newsletters, and would like to support them, please click here for details of how to become a Patron of Gwulo. |

The trays & barrels overlook an open area, with the sea on the right and a road leading into the distance between the houses.

There is still an open area there today. It's where the ceremonies connected with Cheung Chau's famous bun festival are performed.

The road that leads off from the open area is Pak She Street, and it's still there today too. The sandy beach is long gone though, buried under reclamation. If you want to know where it was, just take a walk along today's San Pak She Street as it follows the line of the old beach.

I visited this area with a couple of Gwulo friends in 2015 (see the article "A stroll through Cheung Chau's history" for details.) At the time I took this photo of the Pak Tai Temple that stands at the back of the open ground:

It was built in the 1780s, so it must be there in the 1950s photo. Why can't we see it?

In fact we can - most of the temple is hidden behind the trees, but the temple's ornate gables are peeping through a gap in the branches. I've highlighted them at the bottom of this copy of the photo, so you can see where they are:

I've also highlighted three other buildings we saw in 2015. Above and slightly right from the temple there's a building with a long pitched roof. It's the Cheung Chau Theatre, and in the 1950s it was a working cinema. The building was still standing in 2015, but only just. A look inside showed that a large section of the roof had collapsed:

Fortunately the other two highlighted buildings are in much better condition. The building above the cinema in the photo, and on slightly higher ground, is Cheung Chau's police station:

Then the building on the left overlooking the beach is the St John Hospital:

Both the police station and hospital are still in active use today.

Looking into the distance, the southern hills look very empty compared with the built-up area in the centre of the island. We've looked at the reason behind this before, when we talked about Cheung Chau's European Reservation. The ""Cheung Chau (Residence) Ordinance" was in effect from 1919 til 1946, and during that time the majority of houses that were built were just a single-storey high, and often home to missionaries and their families. Here I've highlighted the single-storey buildings we can see in that area (for a closer look at any photo, click the photo then on the new page click "Zoom"):

How has Cheung Chau changed?

Here's a photo of Cheung Chau from 2003:

Cliff was standing further east than the 1950s photographer, but he's still caught the middle section of the island and the southern hills beyond.

Fifty years on there had been big changes on the southern hills, as they are now covered by buildings. But though we've noted how reclamation has buried the western beach, the eastern beach from the 1950s photo is still with us today.

Gwulo photo ID: A294F

|

Also on Gwulo.com this week... New posts, pictures & comments:

Readers' questions:

Answers to previous questions:

And finally, thanks to everyone who came along to last week's talk I gave to the RAS. We had around 50 people in the audience, and plenty of interesting questions after the talk. |

Comments

Hong Kong and Cheung Chau - Making Changes

I've enjoyed reading the reflective tales of an earlier Cheung Chau and thought perhaps your readers would be interested in learning of the role the island played in England's post-war thinking. The following passage is from my book ASIA BETRAYED that will soon be released in Hong Kong by Earnshaw Books. It's 1942 and Churchill has been to the United States to confer with President Roosevelt:

Returning home, he reflected that his discussions in the White House had not been entirely to his satisfaction. Roosevelt had declared that when the war was over Hong Kong should be returned to Chiang Kai-shek. He was, in fact, working out the details of a compromise deal with the Generalissimo whereby Britain would hand Hong Kong back to China and Chiang would immediately declare Hong Kong a free port. Barely controlling his rage, Churchill huffed, “I will not give away the British Empire.”

Shortly afterwards, a visiting State Department advisor to London announced that “it was time that Britain did the right thing and give up her Asian colonies.” Learning of this, Churchill had the man brought before him. “Hong Kong,” he growled, “was a British creation which had benefited the whole world.” Following up on that, in November 1942 he told the House of Commons, “I have not become the King’s First Minister to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire” and he directed Whitehall to set up a deputation of governments-in-waiting to be “piggy-backed in” the moment the United States liberated Hong Kong, Malaya, and Singapore. Called the Far Eastern Reconstruction Committee, the Hong Kong Planning Unit consisted of nine Hong Kong veteran civil servants, headed by N.L. Smith, Hong Kong’s former Colonial Secretary who had sailed out of Hong Kong harbor on a merchant ship just hours before the first Japanese bombs fell. Ironically, his vessel, the S.S. Ulysses, passed the arrival of his replacement, Franklin Gimson, who was entering Hong Kong on the S.S. Soochow, a cargo ship from Rangoon carrying a full cargo of rice.

"To appease the American liberals" ‒ as they were to phrase it ‒ the Hong Kong Planning Unit weighed making a change to the existing living restrictions in a reclaimed Hong Kong whereby the Chinese would no longer be barred from living on the Peak or from riding on the upper decks of the buses and ferries. The same would hold true for Chinese wishing to build or live on the previously exclusive hills on the offshore island of Cheung Chau. For good measure, the Unit recommended that a future government should no longer be involved in the trafficking of opium. “To comply with the wishes of the United States, it is laid down that government traffic in opium should at least be abolished, and the use of it stamped out. ” [i]

In their words, everything must change, so that nothing might change.[ii]

[i] Pledge to the people of the colonies, given by the Colonial Office, July 1943. Endicott and Birch, Hong

Kong Eclipse, page 279; 318-19

[ii] Philip snow, The Fall of Hog Kong, page 200