May and June have seen the worst of Hong Kong's landslides over the years. In this week's guest post, T.C. Lee, K.Y. Ma and C.M. Shun describe the worst of them all:

With a hilly terrain, Hong Kong is prone to the hazards of landslides during rainstorms, in particular for steep slopes in developed areas. Over the years, there were severe rainstorm events in Hong Kong that triggered disastrous landslides and resulted in heavy loss of lives. Apart from the notorious landslide events in 1966 [1] and 1972 [2], another catastrophic incident in the early part of Hong Kong history occurred in 1925 at Po Hing Fong, a quiet and luxurious residential area in the mid-levels near Caine Road on Hong Kong Island.

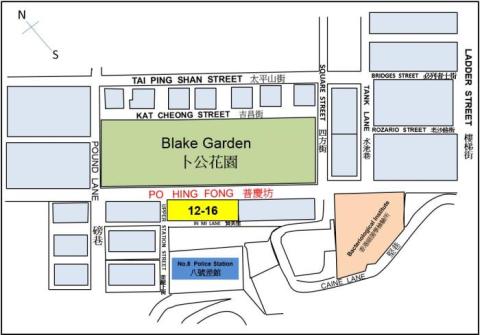

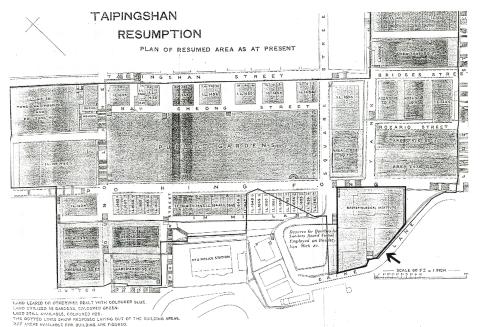

At round 9 a.m. on 17 July 1925, the retaining wall of In Mi Lane [3] which was beneath Caine Road collapsed after days of heavy rain. Large amount of debris ran down to Po Hing Fong and swept away seven four-storey houses from No. 12 to No. 16 (see Figures 1 and 2) with some thirty families inside, causing 75 deaths in this tragic event [4].

Figure 1: A rough sketch of the street map around Po Hing Fong in the 1920s.

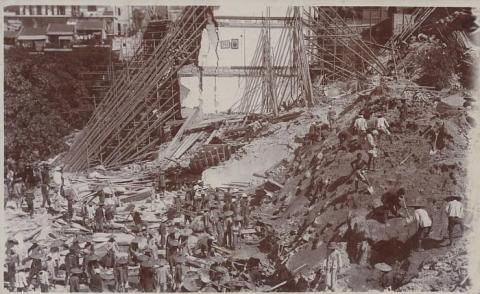

Figure 2: Workers clearing away the debris of the collapsed retaining wall

and houses at Po Hing Fong in July 1925 (photo courtesy of Mr C M Shun).

The victims of this incident were all rich merchants and influential dignitaries, including Mr Chau Siu Ki, J.P., owner of No.12, former Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals and a former member of the Legislative Council, and most of his family members in total 11 persons. His son, Sir Chau Tsun-nin, CBE, survived in this disaster. He was later appointed as a member of Executive Council and Legislative Council, and was knighted in 1956. For No.13-14, the owner was a descendant of Mr Chiu Yu-tin, one of the founders of Nam Pak Hong and the third Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. No.15 was owned by Mr Wong Pak San who was a tycoon and a former Principal Director of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. At the time, this was the deadliest rainstorm in the early days of Hong Kong which hit the headlines of many local newspapers [5] and aroused major concern in the community. The event is also keeping the record of the highest mortality in a single landslide event in Hong Kong (see Table 1).

Table 1: Top five deadliest rainstorm events in Hong Kong (1884-2016):

| Rank | Date | Total rainfall during the event* |

Number of deaths [4, 6-8] |

| 1 | 16-18 June 1972 | 652.3 mm | 150^ |

| 2 | 14-17 June 1925 | 404.2 mm | 75 |

| 3 | 7-13 June 1966 | 679.9 mm | 64 |

| 4 | 12-15 June 1959 | 724.6 mm | 46 |

| 5 | 29-30 May 1889 | 841.2 mm | 27 |

* Based on daily rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory Headquarters

^ The 150 deaths were attributed to the landslides in Sau Mau Ping of Kwun Tong (71 persons), Po Shan Road of mid-levels west (67 persons) and other locations [7, 8]

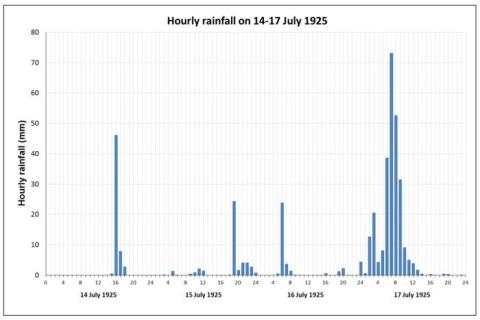

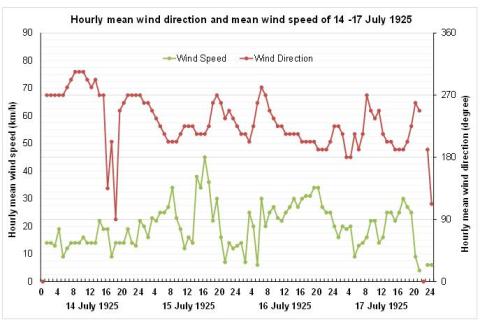

As shown in Figure 3, the weather in Hong Kong was unsettled with occasional heavy showers from 14 to 16 July 1925 with a total of about 140 mm of rainfall recorded at the Observatory during the period.

Figure 3: Hourly rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory

from 14 to 17 July 1925

The weather deteriorated further with torrential rain in the early morning on 17 July and by 9 a.m., more than 240 mm of rainfall had fallen at the Observatory since midnight. Overall, the total rainfall during the period of 14 - 17 July at the Observatory was around 404 mm. While there was no rainfall station near the site at Po Hing Fong, the total rainfall recorded at the Botanic Garden from 14 to 17 July 1925 was about 436 mm (17.17 inches) according to reports by the Botanical and Forestry Department at the time [9], suggesting that the rainfall amount over Hong Kong Island during the period was likely to be comparable or slightly higher than that recorded at the Observatory in Tsim Sha Tsui.

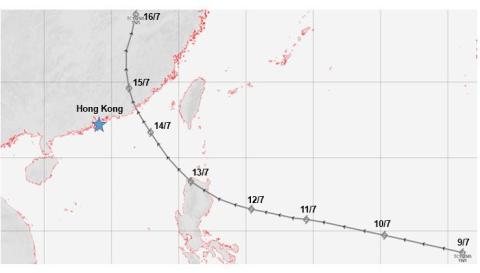

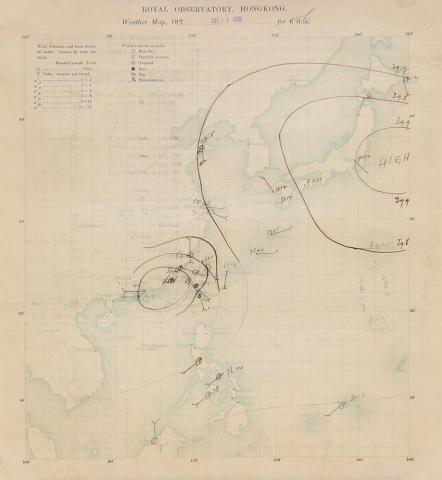

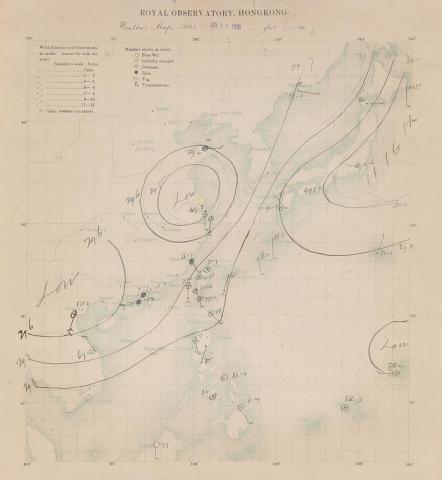

Looking back at the weather charts, a tropical cyclone made landfall to the east of Hong Kong near Shantou on the night of 14 July and tracked northwards, weakening over eastern China in the next couple of days (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Track of the tropical cyclone from 9 to 16 July 1925

that affected the landslide at Po Hing Fong.

The southwest monsoon affecting the coastal area of Guangdong strengthened in the wake of the landfalling tropical cyclone and brought unsettled weather to Hong Kong on 14-17 July (Figures 5 to 7).

Figure 5: Weather chart at 1400 H on 14 July 1925.

Figure 6: Weather chart at 0600 H on 17 July 1925.

Figure 7: Hourly mean wind speed and direction recorded at the

Hong Kong Observatory on 14-17 July 1925. The wind speeds were

calculated from data recorded by the Beckley anemometer at HKO

Headquarters in 1900 and the conversion factors from HKO Technical

Note No. 66 [12].

The Hong Kong Observatory hoisted the local storm signal No. 5 (meaning at the time Gale winds expected to affect Hong Kong from the west) between 4:10 a.m. on 14 July and 10:00 a.m. on 15 July. Coincidently, this was very similar to the main cause behind the historical rainstorm event that occurred just over a year later in 1926 after another tropical cyclone made landfall near Shantou [10]. However, it sounds a bit strange that, according to the track of the tropical cyclones at the time, both storms continued to tracking north after making landfall to the east of Hong Kong, but they still caused heavy rain in Hong Kong. This may not be in line with our general understanding that the heavy rain in Hong Kong induced by the strengthening of the southwest monsoon usually occurs when a tropical cyclone moves west to the north of Hong Kong (at 115 deg. E or its west) after making landfall to the northeast of Hong Kong [11]. Did these two tropical cyclones which brought disastrous rainstorms to Hong Kong come closer to the north of Hong Kong than what were depicted in the historical records of the Observatory? It may be a subject of further research.

During the inquest in the Coroner's court, Mr Charles William Jeffries, the then Acting Director of the Hong Kong Observatory, analyzed the rainfall records in June and July, and indicated that while the rainfall of this event was not unprecedented, it was also not common. A similar quantity had only been recorded on three occasions previously in 1885, 1891 and 1892. There would not be much difference between the rainfall at Po Hing Fong and the Hong Kong Observatory on that day [13]. Summarizing the evidence and statements from the expert witnesses and the engineers of the Public Works Department, the collapse of the retaining wall was mainly attributed to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error in the retaining wall inspection in 1923. The court also offered the following recommendations for improvement [14]:

- Examine retaining walls in the vicinity thoroughly and take immediate steps to strengthen and / or rebuild;

- Appoint a commission of experts to investigate and improve the responsibility and supervision by the Public Works Department of all roads and buildings and nearby hillsides or retaining walls as well as relevant drainage systems; and

- Members of the commission must be independent experts and be empowered to propose amendments in Building Ordinances.

Later on the Legislative Council passed in its meeting on 24 September 1925 a funding of HKD 241,750 for the repair of the rainstorm damages [15]. In the Legislative Council meeting on 22 October 1925, the Government committed to conduct systematic inspection of retaining walls in different districts. As the Government was not obligated to use public funds to maintain private retaining walls, they will inform the owners of the retaining walls with problems to carry out the repair work [16]. Canadian geologist, Dr William Lawrence Uglow, arrived at Hong Kong to conduct a comprehensive geological survey on 6 November 1925 and submitted a study report on 21 April 1926. He pointed out that the weathered granite can be very vulnerable and the retaining wall of Po Hing Fong was a typical example of this [17]. While the report mainly focused on the feasibility of developing underground water resources, it could be considered as a response by the Government to the recommendation of establishing the committee of experts.

Although the rainstorm in 1926 set a historical rainfall record, it was relatively less deadly than that of 1925 [10]. As such, the proposed amendment of the Building Ordinances was not submitted to the Legislative Council until 1935. The amendment was then passed with a number of new measures including regulations on the construction of foundations, restricting the maximum height of a retaining wall to 25 metres, at least one weep hole of not less than 75 millimetres in diameter for every three square metres, installing a hydrophobic layer at the back of each retaining wall, accompanying the design with a stress diagram, and increasing the fine to 500 dollars for any offence against the Building Ordinances [18].

Concluding remarks

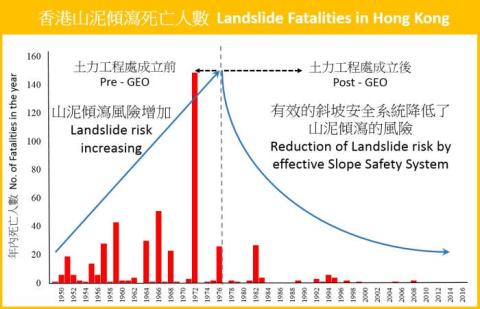

The Po Hing Fong disaster in 1925 is still a record keeper of the highest death toll in a single landslide event in Hong Kong. Although the rainstorm did not set a new rainfall record, the disastrous landslide occurred due to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error of the retaining wall inspection. Given the concerned retaining wall was designed over a century ago (referring to the completion time) and the relatively primitive geotechnical engineering knowledge at the time when compared with the present day, the below par safety margin of the retaining wall was only a post-event assessment and not totally the fault of the then engineers. Accidents and disasters are usually the result of a combination of factors rather than a single one. Coincidentally, the accumulated rainfall of the rainstorm on 18 June 1972 was also not extreme enough to break any historical record[19], but the induced landslides resulted in the highest mortality in the history of Hong Kong. Since the Government established the Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO) in 1977, the upgrading and maintenance work of man-made slopes had improved significantly with a noticeable decrease in the number of landslide fatalities (Figure 8). This truly demonstrates that the Government has been working in the right direction for slope safety and landslide prevention.

Figure 8: Landslide fatalities in Hong Kong (Data source : GEO)

Against the background of climate change, extreme weather events including heavy rain are expected to become more frequent, posing a great challenge to the safety of natural slopes[20]. With a view to preparing Hong Kong for the climate change challenges, we have to learn from the historical lessons to improve prevention measures and make a concerted effort to better the slope safety and maintenance work. Moreover, we should promote public awareness and enhance the resilience of the community against the risk of natural terrain landslides in Hong Kong.

The Authors:

- T.C. Lee: Senior Scientific Officer, Hong Kong Observatory.

- K.Y. Ma: Mr K.Y. Ma is a retired government engineer and also an enthusiast in the history of engineering in Hong Kong. He is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong.

- C.M. Shun: Director of the Hong Kong Observatory.

References:

- T. Y. Chen, 1969 : The severe rainstorms in Hong Kong during June 1966, Supplement to Meteorological Results 1966, Royal Observatory, Hong Kong

- T. T. Cheng and Martin C. Yerg, Jr, 1979 : The severe rainfall occasion, 16-18 1972, Royal Observatory Technical Note No. 51.

- In Mi Lane is no longer exist nowadays

- Item 39, Report of the Director of Public Works for the year 1925

- South China Morning Post and 華僑日報 on 18 July 1925; the China Mail, and Hong Kong Daily Press on 20 July 1925

- Ho Pui-yin, 2003: "Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development", Hong Kong University Press, 364 pp

- Unforgettable Incidents @ Kwun Tong

- Yang, T. L., S. Mackey and E. Cumine, Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Rainstorm Disasters 1972, GEO Report No. 229

- Report on the Botanical and Forestry Department for the Year 1925, Appendix N to Hong Kong Administrative Report for 1925.

- The Phenomenal Rainstorm in 1926

- Lam, H.K., 1975: The August rainstorms of 1969 and 1972 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Observatory Technical Note No. 40

- W.C. Poon, HKO Technical Note No. 66, 1982: Tropical cyclone causing persistent gales at the Royal Observatory 1884-1957 and at Waglan Island 1953-1980

- Hong Kong Daily Press, the China Mail and Hong Kong Telegraph on 25 July 1925

- Hong Kong Telegraph on 5 September 1925

- Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 24 September 1925

- Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 22 October 1925

- WL Uglow, Geology and Mineral Resources of the Colony of Hong Kong, 1926

- Hong Kong Government Gazette, No. 300, 12 April 1935

- There were three consecutive days with daily rainfall exceeding 200 millimetres on 16-18 July 1972, unprecedented in the record of the Hong Kong Observatory

- GEO, 2016 : Natural Terrain Landslide Hazards in Hong Kong

This post originally appeared on the Observatory's Blog. Thank you to the authors for allowing me to share their work here on Gwulo.

Further notes on the number of buildings destroyed at Po Hing Fong

On the 18th of July 1925, the newspapers reported seven houses were destroyed in the landslide. However the Annual Report for the Public Works Department, written at the end of the year, stated that five houses were destroyed. The numbering of the destroyed houses, 12-16, also suggests five houses.

I asked the authors about this, and K.Y. Ma replied:

The report in the Wa Kiu Yat Po explained twice that there were five lots but seven houses collapsed.

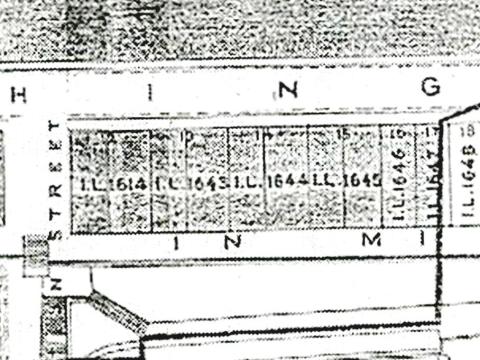

Then this map shows the layout of the lots:

Inland Lots No. 1614, 1643, 1644 and 1645 (Houses No. 12 to No. 15) are double standard lots, while I.L. No 1646 & 1647 (Houses No. 16 & 17) are standard lots. Wealthy Chinese merchants often bought twin lots as they had large families with many concubines and children. It was quite common that they built the house in the twin lot as one entity. That is why No 12 and No 13 were regarded as one house while No. 14 and 15 were regarded as four houses by Wa Kiu Yat Po reporters. Wa Kiu Yat Po reporters said that they regarded partial collapse of No 16 as a collapsed house and thus making the total to be seven.

There is no universal definition of a house, but there is a definition on lot number. That is why PWD only counted the lot. But the media counted in their own way. There is no discrepancy on the definition of collapse between PWD and the media both regarded partial collapse as “collapsed”.

From the Coroner Court proceedings, No. 16 and No. 17 were propped due to their dangerous condition until all rescue work had been completed. PWD then took over the site for removal of these dangerous houses. (SCMP 21, 24, 27, 28, 29,July, China Mail, Daily Press and Hong Kong Telegraph reported the same but on different days).

From the above facts, I interpret that six lots were affected, five lots were collapsed; eight houses affected, and seven houses collapsed.

Related pages on Gwulo:

- Henry Tom BROOKS [1880-1940] was awarded the awarded the Venerable Order of St John of Jerusalem Medal for rescuing victims at the Po Hing Fong landslide in 1925

- Photos of a huge rock that killed several people in a landslide caused by the 1926 rainstorm.

- Photos of the 1966 Chater Hall landslide, another landslide from 1966 near the junction of Peak Rd. and Barker Rd, and yet another at HKU.

- Photos & memories of the 1972 Po Shan Road landslide / Kotewall Road disaster

- A photo and report of the 1973 landslide in front of Thorpe Manor.

If you can add any photos / memories of Hong Kong's landslides, they'll be gratefully received.

|

Also on Gwulo.com this week... New posts, pictures & comments:

Readers' questions:

Answers to previous questions:

|

Comments

Very interesting article. I had researched this landslide a few years ago as I had found almost nothing online about it.

Previously the only picture I had of the disaster was from Ebay found many years ago, a similar view to the above

The Legco minutes from 18th July 1925 on Mr Chau Siu-ki's death:

The Late Mr. Chau Siu-ki

H.E. THE GOVERNOR ~ Gentlemen, Before we proceed in the business on the agenda paper, I desire, on behalf of this Council, to express to the families of all those who have lost their lives on the disaster in the Western part of the town, the very sincere regret at which we have received the news.

Mr. Chau Sin-ki was, for a short time a member of this Council. He then found that his private affairs rendered it impossible for him to render active service to the Council, and asked me to accept his resignation, which I did with regret. I was greatly indebted to him when he came forward a year or two afterwards to take the place vacated by the death Of Mr. Ng Hon-tsz. Mr Chau Siu-ki had a long record of good service to the Colony and his loss has deprived us of a citizen who could ill be spared in these troublous times. I think the Council will desire to express its deep regret, and to send a message of condolence to the family.

Hon. Ma. HOLYOAK—Sir, On behalf of the colleagues l desire to associate myself with the remarks expressed by Your Excellency in connection with the terrible disaster at Po Hing Fong in which our friend and colleague, Mr. Ohau Sin-ki, lost his life as well as most members of his family, and to his surviving sons we desire to extend our deepest sympathy in the terrible tragedy which has befallen his family. lt has been my privilege to know the late Mr. Chau Sin-ki intimately for the last 23 years and of recent years I have served with him in Public endeavour in many ways as well as having been associated with him in this Council, in various Committee, and in business affairs. He was a man for whom I had the highest admiration as one who was just and able in his views and an extremely loyal supporter of the Government of this Colony. We, no less than the Chinese, have lost a. friend to whom we were deeply attached as well as an enthusiastic and able representative in connection with all causes for good. Truly it may be said the Colony is the poorer for his tragic passing.

Hon. MR. KOTEWALL~Sir. My senior Chinese colleague has conceded to me the sad privilege of endorsing, in the name of the Chinese community, the touching remarks of Your Excellency and of the hon. Senior unofficial member; for I had the honour of serving with the late Mr. Chau Siu-ki on this Council for two fairly long; periods, and can also claim a friendship with him which extended over twenty-eight years.The disaster which overtook the Chinese community yesterday was so sudden and of such an appalling magnitude that it still leaves me, who have suffered the loss of many personal friends in it, incapable of properly expressing my feelings. You all know that Mr. Chan Sin-ki was associated with the public life of this Colony for about forty years, and that he had always given to it of his best, unstintingly and without any expectation of reward During that long period he served on innumerable public and charitable committees, and closely identified himself with almost all movements having for their object the general welfare of the Colony.

Though of a retiring disposition, his sterling character, innate good sense, and capacity for public affairs soon won for him a: place in the front rank of our public and commercial life. About two years ago he signified his intention to retire from public life but he never quite gave up interest in all important matters concerning the welfare of the Colony. It was only on the day before the disaster that he attended a meeting in my office in connection with the strike, and another meeting in the same evening concerning the formation of Chinese street guards. But an inexorable fate struck him down the next morning. I am sure that he himself would have preferred this end, cruel as it was, to being spared to mourn the terrible loss, in one single day of more than half of those nearest and dearest to him, including his aged mother, two sons and a daughter, two daughters-in-law, two granddaughters, and his only grandson whose birth last year brought to his yearning heart much unalloyed joy.

Though Mr. Chan Siu-ki is no longer with us, he has left behind him the cherished memory of a life full of good deeds well and unostentatiously done -a life which is a fine example to the younger generation. Our hearts sorrow for his death as for the deaths of so many useful and promising lives. On behalf of the Chinese community, the Hon Mr. Chow Shou-son and I respectfully join in the expression of sincere condolence with the surviving members of Mr. Chan Siu-ki’s family, and also with the relatives of the other victims of this cruel visitation.

All members of the Council remained standing while the above tributes were paid.

Source

I wonder at the official explanation for the disaster, especially with so many deaths of leading members of the Chinese community and their families The hillside above Po Hing Fong has long been known for its springs, due to a geological fault in the area. Tanks No. 1 & 2 were built here c1860 to take advantage of the numerous streams and springs and in the 1963 drought, the driest in Hong Kong history, residents obtained water from them:

“Hundreds of residents around a lane in Western District have found a 24-hour water supply---a natural spring that went almost unnoticed until the current water crisis. Long queues of people now line the lane, near Po Hing Fong, day and night, to draw supplies under the vigilant eye of police constables stationed there to keep order…

South China Morning Post (Hong Kong Friday, June 7, 1963),

Further evidence for the fecundity of these springs comes from the ARP tunnel network built under Blake Gardens in the 1940’s which necessitated the construction of drainage channels in the hillside above to lower the groundwater level. A PWD report from 1979 stated this channel drained 840 British gallons of water per hour. The channel was backfilled in the early 1980’s due to the construction of a primary school

These springs were one of the first culprits to be identified. According to The China Mail (Wednesday July 29, 1925) entitled “Reasons for Po Hing Fong Disaster:

“Mr A W Tickle, Executive Engineer, P. W. D. said that it was his opinion that the cause of the landslip was the presence of springs, percolation from the hills above, and aggravation due to heavy rainfalls. The percolation was probably from land south of Caine Road and had probably been going on for some years…”

It is also mentioned in the China Mail in 1925 that:

“...since the heavy rains that Blake Gardens and the roads in the vicinity had been flooded…”

However, as the article from the HKO points out, the rainfall in 1925, although heavy, was not exceptional. What had changed to cause the retaining wall to collapse?

A brief history of the retaining wall

The wall was originally constructed to support a two storied building on the north side of Hospital Road. It can be seen below in the c1870 photo, likely by Floyd or Thomson, labeled N.

I am unsure what this building was used for originally but in 1890 it became the 2nd Generation of the No 8 Police Station, replacing the original station in the midst of Tai Ping Shan neighbourhood

1890.—Purchase of Inland Lot No. 598 with the Premises erected thereon, for Police Station: $34,000

At this time the verandahs had been enclosed but the building was otherwise unaltered.

The next photo was taken during the construction of Blake gardens in the late 1890s showing the No 8 police station and the retaining wall.

Critically it also shows the removal of the hillside at the base of the wall to create a flat area to construct houses. Prior to the Tai Ping Shan clearances there was an intermediate terrace between Po Hing Fong (Then called Market Street) and the Police Station Terrace. The above picture it can be seen under the matshed being removed. While I am no engineer I can not imagine removing this intermediate terrace did much for the stability of the slope. Below is a picture taken a couple of years later, showing the completed buildings on the left.

The area has been levelled and four storey tenements have been constructed. The edge of No 8 police station can just be seen on the left of the picture. However, while the slope may have been weakened by the excavation it still stood for a further 25 years so there must have been another cause for the collapse.

The reason for the collapse can be found in government documents from the early 1920s. It had been decided that the No 8 police station would be rebuilt and a tender for these works was issued on the 7th November 1924. Subsequent events are summed up in the 1925 PWD Report:

111. Erection of New No 8 Police Station -The tender from Messrs. Kien On & Co. was accepted and work commenced in February. The old building was demolished and foundations for new buildings were practically completed in July when the existing retaining Wall South of In Mi Lane collapsed during heavy rainfall resulting in a subsidence of a portion of the site. As further work was impossible until a new retaining wall has been erected the site was concreted and protected from weather and work suspended.

At the end of the year negotiations for the cancellation of the Contract were in progress.:

1925 Estimates. ...$20,000.00 Total Estimates: $200,000.00

1925 Expenditure. $38,474.89 Expenditure to 31.12.25: $ 38,474.89

With the construction of the new police station in progress the ground, which previously had been protected by the old building was now exposed to the elements. Rainfall which would have normally been drained off soaked into the exposed earth behind the wall. Due to the age of the wall, it is unlikely there were sufficient weep holes to alleviate the buildup of water pressure. Eventually the wall gave way with catastrophic results.

It is unlikely the wall would have given way if it was not for the reconstruction of the No 8 police station above it. I am not familiar with the level of engineering knowledge at the time but it seems somewhat remiss of the PWD department not to realize this. I wonder if, due to the nature of who was killed, and the unsettled political situation of the time, human error by government department was downplayed in the official report in favour of an ‘act of god’ due to the weather.

Additional Sources used:

Groundwater chemistry in the urban environment: a case study of the Mid-levels area, Hong Kong - Leung, Chi-man. Here

Causes of the Disaster

Nice research Herostratus.

The 5th September 1925 edition of the HK Telegraph reported the findings of the Coroners enquiry. It states that the Coroner covered many issues when summing up the case for the Jury, but doesn't mention if he addressed the issue of whether the removal of No.8 Police Station had caused or contributed to the collapse of the retaining wall. It then goes on to report the Jury's findings in more detail, including the following;

"...we are of the opinion that when the inspection of the walls was made in 1923 and prior to the commencement of building operations of the new No.8 Police Station an error of judgement was made in deciding not to rebuild or strengthen the No.1 retaining wall. Expert and witnesses evidence as well as personal examination show in our judgement that the soakage of water from the open lot where the building operations of the new No.8 Police Station were in progress, could at the most have been only contributory causes of the collapse, but it has been conclusively shown that the whole area...has, for a number of years, been waterlogged...demonstrating insufficient drainage..." (bold type added for emphasis)

So even if the Coroner didn't acknowledge the possible culpability of Government officials who failed to anticipate that heavy rainfall upon the cleared site of No.8 Police Station would increase the risk of the retaining wall collapsing, the Jury did address the issue and even described it as an "error of judgement" and a possible contributor to the disaster, although they didn't go as far as to say it was the direct cause. Whereas "error of judgement" can only be regarded as a negative finding its strength was mitigated somewhat by the comment that it led to "at the most...only a contributory cause".

As the history of waterlogging behind the wall was recognized as a contributor, any factors that significantly increased it must logically also be contributors. Yes, it's a bit strange that, having found an error of judgement, the Jury didn't use clearer wording to describe its consequences. Hhmm, semantics!

Other major rainstorms in Hong Kong

The Observatory Blog also has a couple of posts about other major rainstorms in Hong Kong:

Thanks GW, I had only seem

Thanks GW, I had only seem summaries of the report rather than the full document, which didn't mention the removal of No 8 Police Station at all, which I found rather odd. Perhaps I was to hasty in attributing this omission to the age old practice of government officials apportioning blame anywhere but themselves....

I wonder if old coroner reports are available anywhere in HK either paper copies or online.

A bit more about the Police Station site

On page 5 of Hong Kong Daily Press, 1925-09-03, they report the jury's questioning of the two expert witnesses. Here's the section where they're talking to "Mr R. Warren, Engineer with Messrs. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co." who had submitted an expert report.

[...]

The foreman ((of the jury)) said it was his opinion and also that of another juryman that the water sank through from the ground above. ((ie from the No. 8 Police Station site))

Witness said he did not think so as he thought the water was from springs.

Answering questions with regard to the diversion of the water into another channel witness stated that it was the usual practice to put the drainage behind the walls to carry off the water. He did not know if that had been done in this case.

Asked whether if he had been left in charge of the work on the site of the No. 8 Police Station he would have left the site unroofed in the abnormal weather they had had in this season, witness said he would never have roofed it. He would not have thought of it. It would not have dawned on him that the rainfall on the actual area of the site would have affected any of the walls below.

Mr Jenkins suggested that the work proceeding on the site referred to above Po Hing Fong should have been roofed to prevent water reaching the walls below, but witness did not consider this would be necessary.

There's a full report on the Coroner's summing up and the Jury's verdict in the Hong Kong Daily Press, 1925-09-05, starting from page 4.

Do any copies of the expert witness reports still exist?

KY Ma writes:

I am still looking for the Full report prepared by the two witnesses Lt Russell Brown and PR Warren. Mr. Warren was the expert engineer who was happened in HK to study the feasibility of the Shing Mun Reservoir. HK Daily Press on 5th September had extracted their recommendations which HK Government had taken in the new Building Ordinance in 1935. Some of the practices are still using now, though with a new method and material. HK Government had also employed a geologist consultant WL Uglow from Canada, who had also written a report. These two materials may assist to guess the cause of the failure.

Hong Kong's lethal landslide The Po Hing Fong Disaster 1925

I have added six more pictures taken soon after the tragedy in which a retaining wall collapsed during a rainstorm and killed some 78 people.