This booklet was produced by Mildred Dibden circa 1949 to provide information to supporters of the work at The Fanling Babies' Home. There are also stories of the children from Miss Dibden's diary.

The following Advisory Committee names are mentioned:

President Dr Harry Lechmere Clift and his wife Winifred were experienced CMS then BCMS missionaries originally from Nanning, Guangxi province, China. In the 1930s Dr Clift set up practice in Nathan Road, Hong Kong, and also started the Emmanuel Mission Church and Bookroom there. It was he and his wife who had encouraged Mildred Dibden to start up on her own in Hong Kong in 1936, when she found no backing forthcoming from any UK missionary society for taking in abandoned babies. The Evangelical Fraternity supported Miss Dibden from when she started up with her first baby in a small 2-bed rented flat in Tsim Sha Tsui up to the time she moved to Fanling in 1940. The aim was to take in babies (not children) and an age limit of two was set because there were other charities catering for children at the time.

The Bragas were a prominent HK family of Portuguese origin who were close friends of Mildred Dibden and Lucy Clay and keen supporters of the Home. Hugh Braga (Chairman) was an engineer who rose to become General Works Manager, Hong Kong Engineering and Construction Co. He gave Mildred Dibden valuable support from when he first got to know her though the Emmanuel Church in about 1933 in her early years in HK, then when she started the Fanling Home, and particularly after the war when the roof of the Home was found to be eaten through by white ants. When the Home Advisory Committee was formed in 1946, Mildred invited Hugh Braga to be chairman.

Hon Secretary Mrs H Braga refers to Nora Braga (nee Bromley), who was a BCMS missionary prior to her marriage. She had spent two years at Dalton House in Bristol 1930-31, training with the BCMS before coming out to Hong Kong to serve first of all in the BCMS Children’s Home at Broadwood Road (to learn the language?), and then at the BCMS Home and School in Haiphong in French Indo-China. After her marriage to Hugh Braga in 1935 they lived at ‘Hillview’, 18 Braga Circuit, Kowloon, and their home became a centre of hospitality for Nora’s BCMS colleagues and other China missionaries.

Hon Treasurer Mr W Goon - There is a Willie Goon who gets several mentions in Beth Nance’s life story as he was a friend of the Nances. He must have been a Chinese national as he wasn’t interned during the war. Before the war he worked with them in the Clifts’ Emmanuel Mission. During the occupation he and other uninterned nationals kept the Mission Church and book room going. After the liberation he visited friends (Clifts and Nances and others) in Stanley Camp looking very thin and emaciated but having a wonderful smile on his face.

Rev Erwin W Raetz (an American) was General Superintendent of China's Children Fund in China, and as CCF supported 54 Fanling girls at this time (1949), he was CCF's representative on the Committee. Repatriated to the USA in 1942 he was back in China after the war.

Mildred Dibden herself was a former BCMS missionary. Now in her 40s, she had over 100 children in the Home since the losses during the war.

The founding date of November 11th became the Home Birthday and was celebrated over 2 days every year, as for many of the infants there was no known birth date.

My thanks to Stuart Braga for information on the Bragas.

Comments

Text

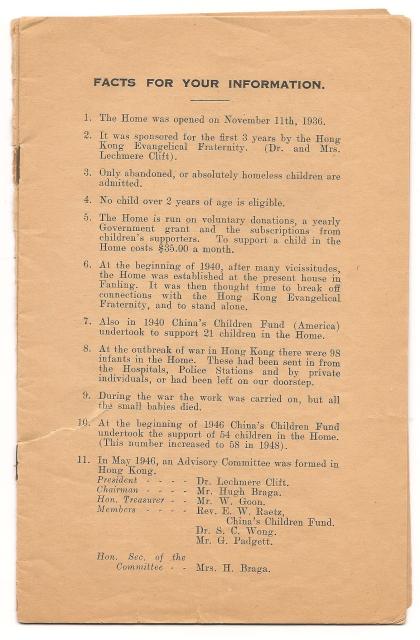

FACTS FOR YOUR INFORMATION.

1. The Home was opened on November 11th, 1936.

2. It was sponsored for the first 3 years by the Hong Kong Evangelical Fraternity. (Dr. and Mrs. Lechmere Clift).

3. Only abandoned, or absolutely homeless children are admitted.

4. No child over 2 years of age is eligible.

5. The Home is run on voluntary donations, a yearly Government grant and the subscriptions from children's supporters. To support a child in the Home costs $35.00 a month.

6. At the beginning of 1940, after many vicissitudes, the Home was established at the present house in Fanling. It was then thought time to break off connections with the Hong Kong Evangelical Fraternity, and to stand alone.

7. Also in 1940 China’s Children Fund (America) undertook to support 21 children in the Home.

8. At the outbreak of war in Hong Kong there were 98 infants in the Home. These had been sent in from the Hospitals, Police Stations and by private individuals, or had been left on our doorstep.

9. During the war the work was carried on, but all the small babies died.

10. At the beginning of 1946 China’s Children Fund undertook the support of 54 children in the Home. (This number increased to 58 in 1948).

11. In May 1946, an Advisory Committee was formed in Hong Kong.

Fanling Booklet

Front cover of the booklet. It runs to some 18 pages. The paper is very fragile. I would guess the date to be between 1948 (as mention is made of Lucy Clay who joined the work then) and 1950 when Mildred Dibden left. 1949 would seem to be a fair guess.

A note on the back of the booklet says - 'This little book is printed to give information to new friends of the Babies' Home, and the stories it contains have been gathered over a period of several years and some have been printed previously.'

War orphan

As well as information about the Home, the booklet gives some stories from Miss Dibden's diary, which give a glimpse into life as she experienced it then. This is one of them:

A strange little girl came to us during the last months of the war. The great world had not been kind to her. She stood, holding a filthy hat with a scrap of clothing, her Chinese suit bedraggled with rain and mud. Her long black lashes, her black hair and sunburnt skin gave her a strangely dark appearance, she stood there, utterly and acutely miserable, and fixed her large dark eyes on my face! Throughout the whole conversation regarding her - her glance did not waver. Silent, resigned and hopeless she stood waiting for what would happen next. It was strange how beautiful she was. Her features were perfect, and as yet untouched by the Beriberi which made her little swollen feet so painful.

"Nothing could be worse than the past," she seemed to say, "Hunger - dirt - wet - pain, this wretchedness is life! What these queer grown-up people talk about doesn't matter - only to lie down, lie down, now, NOW!" Her eyes wavered, I stepped quickly forward and placed her gently on the ground.

"Yes," the man who had brought her was saying, "she has been there on the grass for several days. We do not know where she came from, but we have given her water to drink, and sometimes a little rice. We have so little rice ourselves !"

There followed weeks when night and day we struggled for her life. She lay there in the cot - too weak to move or speak, her lovely face now marred by the swollen, grey glassiness of Beriberi in its final stages.

And then there came a day when someone said, "The swelling is going down - her colour is better!"

And then - almost past belief - "I think she will recover !"

Very slowly she crept back to health and life - but not normal life. Poor little girl. It is as if she never forgets! As if, surrounded as she is with the fun and laughter of happy little children - she yet lives alone in that awful past, where fear, hunger and exposure deadened all feelings and emotions. She waits silently, never speaking except in necessity, never playing. She takes her share of rations -neither pleased nor sorry at an extra treat of sweets or biscuits. Unresponsive to love or fun, she does what she is told, no more.

Poor little girl! Can we by prayer and love, unfailingly given, win her to the natural joy of childhood?

Strange, cold, unlovable - in spite of these lovely eyes - can we, by the Power and the Grace of God, make a normal child of her? She is not dull at school, but rather shows intelligence when she does take any part in the Reading or Writing lessons. Is it true, as many say, that she is sullen and obstinate? Is it true that she, a wee girl of about 7 years, is cruel and spiteful?

I don't know! But yesterday, as I stood by the door, she took my hand in hers! - Oh rejoice! Rejoice over this - the first sign of a natural, normal, living little heart! If we can teach her to love we can help her to become a happy, loveable child, whose heart is with - instead of against - everyone.

Clearly the '2-year-old' rule was not set in stone for this 7-year-old and very needy little girl.

Fanling Booklet pages 3-4

The booklet, written circa 1949, gives answers to some of the most frequent questions from supporters of the work. Pages 3 - 4 deal with the number one question, 'Why are babies not wanted?' Miss Dibden writes (summarised):

"WHY ARE THE BABIES NOT WANTED?"

Superstitions surrounding newborns are too numerous to list, and many remain unknown to me. In traditional Chinese culture, the birth of a girl is often met with disappointment, as boys are preferred for carrying on the family name and honoring ancestors. Girls, destined to marry into another clan, are seen as less valuable.

At birth, a girl is scrutinized for any unusual traits—believed to signal possession by evil spirits. Misfortunes around the time of her arrival, from illness to livestock death, are blamed on her. Villagers may declare she’ll bring sorrow or ruin, even if she’s simply born with a tooth.

Do people truly believe this? Among rural, uneducated communities, yes. Some men may quietly disagree, but with daughters already doing household work, they see no need for another. Tragically, this fuels harmful superstitions, and unwanted baby girls are sometimes abandoned in remote places.

In traditional rural China, sick or premature baby girls are often abandoned, while boys receive every effort to survive. Even a healthy girl may be cast out if she later falls ill—nursing her is deemed a waste of time. Though a mother may grieve, the family decides, and the child is left beneath a tree while the mother returns to work.

Authorities rarely intervene. In Hong Kong, where birth registration is enforced, abandonment is done in secret, and the child’s origins vanish behind the phrase, “Ngoh m chi” — “I do not know.”

Western influence and the equal care shown to girls and boys have begun to reshape attitudes, especially among educated families. Christian missionaries have helped shift perspectives in poorer communities, but superstition and custom remain deeply rooted. Even after a century of British rule in Hong Kong, cruel practices persist under the shadow of ignorance and tradition.

Child selling, though illegal in Hong Kong, still occurs—especially among those arriving from inland China unaware of the law. Boys are rarely sold, but when they are, they fetch a high price as adopted sons who carry the family name. Girls, however, are sold cheaply to serve as slave girls or future daughters-in-law, expected to be obedient and bear sons.

The darkest fate awaits girls sold through middlemen to women who raise them for resale into brothels or “Flower Boats.” Poverty is often the driving force behind these transactions. Parents may not know the buyer’s true intent, believing the girl will become a “Mooi-tsai” (slave girl). In Hong Kong, such sales are forbidden, and owners must report the child so her welfare can be monitored.

Extreme poverty also leads to infant abandonment. Malnourished mothers may feed their babies briefly, but once milk runs dry or work is disrupted, the child is left on a hillside or doorstep. When asked, the answer is always the same: “I do not know.”