Guest author Patricia O'Sullivan describes this bloody murder, and the flawed police investigation that followed.

Often, waiting at the bus stop at Pacific Place, I’d see a No.1 bus roll past and wonder about the murder at Felix Villas.

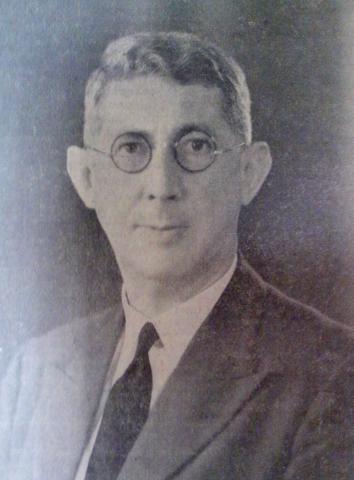

I knew that Tim Murphy had been involved in this case, but, aside from noting the headlines, I’d not properly looked at it. Murphy was the ‘poster-boy’ for the Newmarket HK policemen, being one of the first constables to rise through the ranks to become a gazetted officer, and I had plenty of material about his police activities from the papers as it was, so I’d never quite got round to reading the case. But then I stumbled across the Antiquities and Monuments listing for the residential building and became curious.

Tim Murphy, poster-boy policeman

Tim Murphy, whose career spanned most of the first 40 years of the last century, had been born in Newmarket, Co. Cork, Ireland in 1882 and came to HK on the urging of his uncle, former Naval Dockyard Police Inspector-turned-property developer, William Lysaught.

A wiry, sharp-witted and hardworking young man, he soon gained a command of Cantonese and was quickly moved into the Detective Branch, as the CID was then called. He had the rare distinction of gaining two (of a possible four) merit medals in one year, and by the 1920s his name was rarely out of the papers in connections with some daring arrest or successful investigation. In 1923 he was awarded the highest honour, the King’s Police Medal, for his leadership in the Canton Road Affray. By 1930 he had assumed charge of the Criminal Investigation Bureau, becoming an Assistant Superintendent the following year, thus joining the executive team of just twelve men. But, as I found out, the investigation of the brutal murder at 9 Felix Villas in the early hours of 12th December 1930 would not be his, or the Bureau’s, finest hour.

The murder, 12th December, 1930

At about 5 a.m. that December morning, Ka Sau-hei, No. 1 Houseboy and his wife, Li Yah-wun, were awakened by someone calling the man’s name. The voice must have been familiar, for he went straight out into the passage. But before he’d even turned on the electric light there, he had been stabbed three times, the fatal blow going right through his heart. His cry of Ah wai! had been heard by his wife, as had his fall - but she hesitated before rushing out, for the assailant had, she said, appeared in the doorway of their room for a moment before making his escape.

The setting, Felix Villas

Felix Villas were built in 1922 by businessman Mr. Felix Alexander Joseph - rather gracious, well proportioned pairs of residences right round the headland of Mount Davis Road, with views south and west between Lamma and Lantau, and out to the South China Seas. Ten houses were built above Mount Davis Road, with eight facing them on the lower side of the road.

The houses had to be no more than 35ft. tall, so had two storeys built upon a semi-basement, which housed the kitchen and utility areas with the servants quarters projecting into the rear yard. This yard opened onto a service, or scavenging, lane and behind that was the steep incline of Mount Davis - Mo Sing Leng. It was in the basement that the story is set. But before we descend there, the ‘above stairs’ folk should be introduced briefly.

The cast of characters in the house that night

The head of the house, Frenchman Monsieur René J. F. L. Ohl, was manager of Messagier Maritimes shipping agency. He had arrived in the colony in the last couple of years with his wife and two small children. In the next ten years they would move house a number of times, to Stubbs Road, then to Conduit Street, and even by the time the murder case came to trial, they had moved across the road to No. 2 Felix Villas. He served as Argentinian Consul for periods before 1938.

M. Ohl’s house staff consisted of a cook, a No. 1 houseboy, a coolie, a wash amah, a baby amah and a European nanny. All bar the nanny lived in the basement quarters. Thirty-four year old Ka Sau-hei had been in M. Ohl’s employment since the latter took up residence at Felix Villas. He was married, but his wife, although a frequent visitor to the house did not work or live there. Ka had been promoted from coolie to houseboy three months earlier, on the dismissal of former houseboy, Tsui Suk-mei. Ng Hing-wing had then been employed as coolie on the recommendation of the cook (whose name is not reported). The men all came from Shanghai and had been in Hong Kong a few years.

Screams and blood – the police are called

At about 5 a.m. the Ohl's were both woken by the screams and commotion from the basement and Rene Ohl rushed down to investigate. When he saw his Houseboy lying in a pool of blood at the foot of the stairs, he went to phone the police, but finding that he did not have the number of the local station in his address book, he wasted no further time, hurrying to get into his clothes and drive the short distance to No. 7 (West Point) Police Station in his car. He returned some minutes later with Sgt. Clark and some constables, one of whom was dispatched back to the Station to phone through for the detective squad, and it was not long before the senior team arrived. Both Acting Chief Detective Inspector Alfred Reynolds and Acting Assistant Superintendent Tim Murphy attended, the former coming from his quarters at the Central Police Station, whilst the latter had been roused by the telephone in his Caine Road apartment and had driven himself to the scene.

A likely suspect

But even before the detectives arrived, Sgt. Clark reckoned that they might have an idea about who was responsible. The distraught wife said that she had seen the man before he escaped - and claimed that she knew him. He was, she had apparently said, the previous No. 1 Houseboy, Tsui Suk-mei.

Murphy questioned M. Ohl first, learning of the disposition of the household, and, heard about the recent changes. Ohl explained that he had been loath to get rid of twenty-two year old Tsui, who was good at his job, but there had been too many quarrels between the staff, and it was on account of complaints about this man from both Ka and the cook that he had reluctantly decided to let Tsui go. He had given the former houseboy good references and pointed him in the direction of another post, which Tsui had secured a few days after leaving Felix Villas.

Murphy then interviewed the cook, who said that he had been asleep in the next room, which he shared with the coolie. He described waking up and going to investigate, but had been too late to see the murderer. However, in the minutes after the attack, Ka’s widow had described to him the man she had seen standing in the doorway. He was dressed all in white - shirt, trousers and socks, except that there was a dark stripe down the trousers sides. The woman had also said that his shoes were dark-coloured, too. Did he know, asked Murphy, that Li was saying that this was Tsui? Yes, it sounded like him from her description. Tsui had been the source of many quarrels and the house was much quieter now he had left, and there’d even been a fight.

The coolie, Ng Hing-wing had nothing to add about the events but declared that he had seen one fight, mentioning that Tsui had visited 9 Felix Villas on a few occasions since he had been dismissed. The widow’s statement was, unsurprisingly, rather confused. When sorted out as best they could, it seemed that the couple had got up at about 4 a.m. After a little while they had returned to bed and to sleep, but when at 5 a.m. they had both heard the voice calling out, only Tsui had got up. Yes, he had put the light on in their room, but not in the passage - she’d seen him turn as to switch that one on, but then he cried out. Curiously, the police did not - or perhaps could not - get a description of the attacker from the widow, but were ready to rely on the second-hand account from the Cook.

Bringing the suspect in

On this basis Murphy decided to bring Tsui Suk-mei in. Did anyone in the household know where he was now? Yes, everyone knew, apparently and M. Ohl was able to confirm that Tsui was now working at 28, Kennedy Road. Detective constables were dispatched thither, and found Tsui in bed in one of the rooms of the servants’ quarters. He was dressed in a white shirt and trousers, the latter with a dark stripe down the seam. He had no socks on, but pulled on dark shoes when the police arrived. He usually had the room to himself, but that night two other men were also there, one sharing his bed while the other had a camp bed. When asked by the detective, they both said that Tsui had not been out of the house during the night, but the constables had been provided with a warrant, so Tsui was duly arrested and taken to No. 7 Station, where he sat in a cell for some time until interviewed by both Reynolds and Murphy.

Spots of blood on the tail of his shirt and discolouration around his fingernails was noticed, and when extracted, this red matter was sent to the Government Bacteriologist for examination. The widow’s description of the man and her reported recognition of him, the tales of the fight and arguments in the house and now these blood stains justified, the detectives stated, bringing this man before the magistrate with a view to having him remanded a week or two, long enough to carry out further searches and questionings. But perhaps more to the point, they had no other leads. M. Ohl had not seen anyone except a lone servant in the street when he went to fetch the police. No weapon had been found and although the attacker had made his escape by unbolting the back gate (having jumped over the wall to gain entrance), there was no mention of fingerprints having been taken there or elsewhere in the house.

On Monday afternoon, 15th December, therefore, Det. Sgt. Flattery was given the task of bringing Tsui to the Magistracy and appearing for the police to ask the magistrate for a week’s remand on the capital charge. This was repeated twice more, until Murphy was satisfied that they had sufficient evidence to bring the case to trial.

The evidence is presented at the Magistracy

On Monday, January 5th, 1931, Mr. R. E. Lindsell, First Police Magistrate was behind the bench whilst Tim Murphy prosecuted. Tsui had no legal representation, but knew that, should the case go to the Assizes, he would be provided with a barrister, since this was a capital charge.

With plans and photographs of the house, Murphy opened the case by describing the location of the crime and then the staff of 9, Felix Villas. The events of the early morning of 13th December, from the perspective of the widow, Li Yah-wun, were then recounted. “As a result of a statement made by the woman to the cook,” Murphy explained, “the Police went to 28, Kennedy Road and there arrested Tsui Suk-mei, the former Houseboy.” He continued that, according to the men who happened to be sharing his room that night, who were friends, of the Felix Villas’ cook, all three had gone to bed at about midnight. Tsui had risen from his bed at about 3 a.m., got dressed and crept out, returning at 6 a.m., and going back to bed without getting undressed. It was believed by the police that he then made his way to 9 Felix Villas where he only had to jump over the back wall to get into the yard. He had a key for the door, because before he left M. Ohl’s employment he had had some spares cut and taken them with him. He opened the door, calling out to Ka as he did so. As the latter emerged from his room and turned to put on the light, Tsui struck him with a kitchen knife, the blade cutting through his jugular vein and reaching his backbone. Ka cried out and tried to snatch the knife, lacerating his hands in the process. But Tsui, with all the advantage of surprise, stabbed again at his back as Ka staggered. The third blow was to the front of Ka’s chest, slicing right through the man’s heart. Ka doubled up, stumbled a step or two towards the stairs and collapsed, dying almost immediately.

Ng Hing-wing and the cook were then brought by the prosecution to give their evidence. Ng spoke about the how keys had gone missing, and stated that he had seen the fight some months earlier between Tsui and Ka. The court had earlier been told how Ka had fitted a padlock onto his door, in addition to the regular lock, and kept an iron bar beside him in the room, apparently fearing for his life. However, Ng had never seen the iron bar. Mr. Lindsell found his evidence confusing and was obviously not convinced about its veracity. The cook told about the trouble there had been with Tsui, about the quarrels and the fight and how he too had had quarrels with the man. The fight had started with Tsui throwing a cooking pot at Ka, cutting his head slightly, because the older man had not taken orders from the Houseboy and had lasted about ten minutes and had ended with neither party ‘winning’, really.

The next day Tsui made a long statement to Mr. Lindsell that gave the impression of real candour. He and Ka had had their differences, yes, they had quarrelled and had that one fight, but he, Tsui, didn’t hold a grudge against him. They made up afterwards, agreeing that there had been a misunderstanding. He had no reason to kill Ka, indeed, he never would. He questioned how he was supposed to have made a round journey, much of it along unlighted lanes, from 28 Kennedy Road to Felix Villas in that time - he said it was four miles each way, if he had made that journey, why was it he was not stopped - or even arrested (for being a ‘suspicious character’ out so late)? The journey would have been on foot, there were no night buses at the time and there was no suggestion that the police found - or tried to find - a ricksha driver who had conveyed him to and from the house. He agreed that there were bloodstains on the tail of his shirt, but he normally wore his shirt tucked into his trousers. It really wasn’t uncommon to find bloodstains on a servant’s clothes, anyway. He believed that the blood found under his fingernails could have come from scratching himself, or could have been chicken’s blood. As for the widow’s evidence against him, well, she had been living at 28 Kennedy Road recently, she knew his clothes and what he usually wore and he thought she had fabricated this story. But as far as he knew, they were on good terms, so he couldn’t understand it, really.

After this, Mr. Lindsell brought proceeding to a close. He had, it was noted, continued sitting after the customary hour and carried on till 6pm in order to get the case on the calendar for the next assizes sitting, which was due to start in just over a week’s time. Whether he had doubts at this stage is not recorded, but the police were still sure of their case, so he allowed it to proceed.

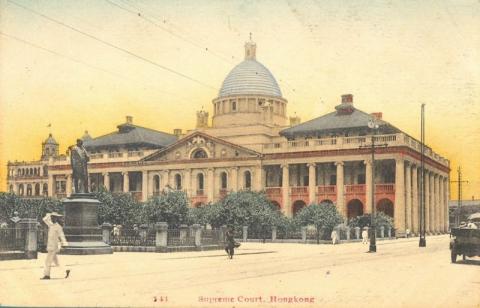

The trial opens at the Supreme Court …

The case Tsui Suk-mei v. Crown opened at the Supreme Court on Monday 19th January before the Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Wood with Mr. S. Fitzroy, Assistant to the Attorney General prosecuting.

To Tsui’s good fortune, his case had been given to Leo d’Almada e Castro Jn., who had only been called to the Bar in London four years earlier and was thus the newest barrister on the block in Hong Kong. As such, he picked up the Crown-funded (and thus none too well remunerated) cases - but as an already able and confident lawyer, he was keen to establish his reputation and was becoming known as a force to be reckoned with, not averse to criticising his opposing counsel in court, be they never so high.

… where the prosecution’s case soon falls to pieces

The first day of the trial was given over to the recounting of the incidents of the night, and the prosecution’s claim that there was direct testimony that the assailant was the defendant, that he had been seen and identified by the woman who was only eight feet or so away from him. It was on the second day when ‘evidence’ started to be more closely questioned that the case really started to unravel.

The court now heard how Ohl had been reluctant to let Tsui go since he knew his job and was a sober and quiet man normally, although there had been one occasion when he had to separate Tsui and the cook who were fighting. The coolie, Ng, had to admit that his story about the fight between Ka and Tsui had all been hearsay, and that it was before he started working for M. Ohl. In fact, the two men had had seemed friendly enough together when he had visited the house. The cook then explained how the Ka had got Tsui into trouble with M. Ohl by not following his instructions and it was as a quarrel about this that the fight had started. Yes, Tsui had visited the house a few times since his dismissal - he normally sat in the Wash Amah’s room and talked with some of the servants there. Why had Ng - who only joined the household after Tsui’s dismissal been at 9 Felix Villas before then? Well, that was because he was the cook’s brother, yes, and the cook had got him the job back in October. And as to the keys, well, four had been seen in Tsui’s room when he had first had them made, but the cook didn’t know if he had kept any, usually they were kept in the doors, as the one type fitted all the doors in the servants’ quarters. In fact, they had found two of the keys now, although the other two were still missing.

The defendant, when cross examined, was as candid as he had been before Mr. Lindsell. He had been in Hong Kong for about two and a half years, first employed as coolie in another house in Felix Villas, then going to M. Ohl after a few months, on the cook’s recommendation. He had known both Ka and the cook for some time. He admitted to quarrels with both the cook and Ka in the course of the couple of years, but he’d never fought with Ka before that one time. Li, Ka’s wife, had not lived at Felix Villas, would visit sometimes, but she was a noisy woman and, as Houseboy, Tsui had had to reproach her for making such a commotion on a number of occasions. After he had left M. Ohl’s house and gone to Kennedy Road, she had moved there too, not at his invitation, but at the suggestion of one of the other servants in that house. She was no different there and he had complained of her noise once or twice a week.

He, Tsui, had met Ka by chance at Kowloon Ferry pier about ten days before the murder, and had exchanged greetings, but he had not been to the house since that time, and certainly had not taken keys from there. When questioned about the night of the murder, he explained that he had gone to bed at about 9pm, but was woken at midnight when the other men came in with some food, which they’d all shared. He then went to sleep again until about six thirty - he had got up to go to the lavatory and dressed in his shirt and trousers, then went outside to see how much light there was - he wanted to judge the time, as he didn’t have a clock or watch. He knew roughly from the amount of light in the room, but by looking at the sky he could reckon it to be between six thirty and seven. He went back to bed, still dressed, for a few minutes more sleep, and was then woken by the police arriving. The other men, when asked by the constable if Tsui had been out that night had said that he had not. He couldn’t account for why they had changed their evidence. Yes, these men were friends of the cook at Felix Villas.

By this point, the Chief Justice’s questions to the defendant suggest that the case is near to collapse. Could Tsui think of anyone who would have a grudge sufficient against Ka and would know the layout of the house?, asked Mr. Justice Wood. No, he could think of no one. Did the two men gamble together? Well, sometimes, not often. Ka had owed him some money, but paid it to him before he, Tsui, left the house. Mr. Fitzroy was left with the widow’s testimony and the fact of bloodstains on the shirt with which to sway the jury.

Mr. d’Almada, on the other hand, had plenty of points to make in his client’s defence. Where, he asked, was the motive? The Crown had failed to provide any evidence of hostility between the two men. That Ka had taken over his job - when Tsui had secured another as good just days later - could hardly be given as a reason and equally, surely quarrels and a fight that had been made up were no provocation for a murder over two months later. The prosecution had not accounted for how Tsui was supposed to have got between Kennedy Road and Felix Villas and back in the available time. As to the statement from the men in Tsui’s room, they had been held in the Central Police Station before formal evidence was taken - but by this time they would know the charge Tsui was facing, and had changed their story to fit what was wanted. Mr. Fitzroy had got the medical witness to agree that it was possible that these wounds could have been inflicted by a blade between 6-8 inches long without the attacker getting blood on himself - but whilst all things were possible, he asked the Jury to remember that all things were not probable. And as to the widow’s identification - Mr. d’Almada did not suggest that she was lying but reminded the jury that she had seen the attacker for just a few seconds and immediately afterwards found that her husband was dead. Was this secure enough to convict anyone on?

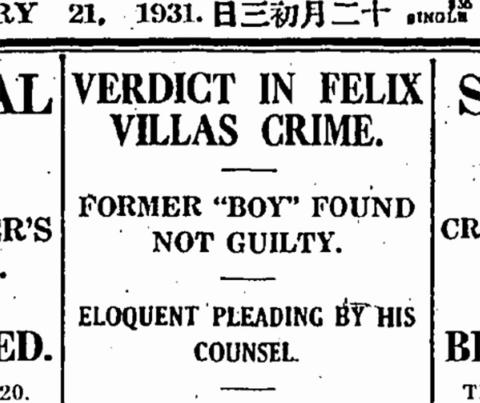

Not Guilty!

It sounds as if the Jury didn’t even reach the retiring room before being sure of their decision, for the papers all record that after an absence of only one minute they returned with a unanimous ‘Not Guilty’ verdict and the Chief Justice acquitted Tsui.

What were the after-effects of this bungled investigation?

I would love to know if ‘words were had’, either by the Chief Justice or his superior officers with Acting Assistant Superintendent Murphy. After all, he had been in charge of the case throughout and the conclusion of the court seems to be that it should never have come up for trial. The motive presented was always tenuous, and the time-frame challenging, at the very least. By his showing in both courts, Tsui was an articulate and intelligent man - did Murphy stop to wonder why, knowing that he had been almost certainly recognised, would go back to his regular address? Murphy and his colleagues seem to have heard only what fitted in with their assumptions when questioning the servants. Had they considered the network of relationships within this group of people, or how all the case against Tsui, aside from the widow’s apparent recognition of him, centred around the cook - he had the description - apparently from Li. He too had had fights with the man. He had put his brother in Tsui’s place … and then his friends are in his room that night and change their evidence to suit.

So who did kill Ka Sau-hei? Not the cook, probably, but he does seem to have had a motive to stop the police looking further, and to implicate Tsui, even to the peril of his former colleague’s life. The police do not seem to have pursued the matter - doubtless, a month after the events, little physical evidence could be found, yet that was only ever going to be part of the story.

Why was this case so shoddily treated? Was it for them “just another ‘coolie class’ murder” only getting publicity in the English language press because of the prominence of the householder? And a fight between “foreign” Shanghaise at that? There is no criticism of the police in the press, and no curiosity expressed as to what had happened. And whether Murphy was ‘spoken to’ or not, the failure of this case did not to affect the success of his career, as his acting post was confirmed on 5th July that same year. Over the years that I’ve been researching the police careers of my Newmarket men, I’ve become rather familiar with tales of their successes and have uncovered remarkably few less positive tales. So much so, indeed, that its almost a relief to find that the highest-flying man of that group did, occasionally, have feet of clay like the rest of us.

And what happened to those involved? Did the cook and coolie stay with M. Ohl when he moved to 2 Felix Villas? Did Tsui keep his post at Kennedy Road? As so often, we can trace the futures of the Europeans involved, but not the Chinese. The men and one woman really concerned here have all disappeared into history, they had their fifteen minutes in the spotlight, but there’s no saying what they did next.

Patricia first encountered Tim Murphy during the research for her book, Policing Hong Kong – An Irish History. She combined her own family's history with meticulous research, to tell the story of a group of men from a small town in Ireland who worked as policemen in Hong Kong.

The book spans the years from the 1860s till shortly after WW2, and covers three main areas of Hong Kong's history during that time: the development of the police force, the Irish community, and life as a working class westerner.

Click for details of how to order a copy of Policing Hong Kong from Gwulo.com. We deliver worldwide.

Corrections:

- 16 Dec 2018, corrected the name of the original owner of Felix Villas from Mr. Felix Alexander to Mr. Felix Alexander Joseph. Thanks to Howard Elias for catching the error.

Comments

intriguing story

What a great story. Thanks for sharing.

Officer Tim Murphy

Hi Patricia and David, I read the article on the Felix Villas Murder with great interest.

Apparently Det. Tim Murphy was the same police officer involved in another sensational case that I wrote about: The Trial of Jesuina Xavier in Feb. 1931.

https://www.academia.edu/41079595/Underclass_Marginalization_in_1930s_Hong_Kong_The_Trial_of_Jesuina_Xavier.

I also noted Officer Murphy's lack of diligence in finding critical evidence in the defendant's home.

Thought you and your readers might find the parallels interesting.

Best regards,

Roy

Dr. Roy Eric Xavier

U.C. Berkeley

P.S. the article is a chapter in my new book to be published in late July: The Macanese Chronicles: A History of Luso-Asians in a Global Economy.

Officer Murphy

Hi Roy,

I've just been enjoying reading your article again. It's only on the second reading I noticed it mentions Michael Murphy, not Tim. Patricia explains that Michael and Tim were cousins.

Best regards, David

Timothy Murphy

In the headlined photograph Murphy,wearing full dress as a Gazetted Officer sports the following medals, from the left as viewed - Kings Police Medal,then Hong Kong Police Merit Medal Classes 2,3 and 4.Note elaborate headress badge,a silver Royal Cypher,lesser mortals had to make do with a basic Kings Crown.

Both accounts very

Both accounts very interesting.

It's easy though to criticise somebody in hindsight many years later - looks like there were mistakes made but the author doesnt really give any alternate suspects, just a few maybes. It wasn't the first time and won't be the last that a good lawyer has won the day. Maybe the police didn't investigate further as they knew who it was but couldn't prove it. A few years back I got to know a policeman from just a bit later in that era (late 1930s) and he mentioned that they didn't have all the investigative processess of today ('today' was the late '90s) and relied a lot on 'instinct' which coupled with a local population who would often close ranks didn't always produce results.

The Xavier case seems to be 'she said, he said' with a lot of the evidence being given by her relatives.No doubt a very troubled person.

As for the wounds - 'none were considered serious because the bullets were old and detoriated' - being shot three times is surely more than an accident.

In fairness it says a lot for the rule of law and 'administrators' of it in Hong Kong at that time in both cases despite the 'racial and class boundaries' which is the thrust of the Xavier paper.

Acting Chief Justice Wood I think

It seems that Mr Justic Wood was "only" Acting Chief Justice from time to time between 1927 and 1933, presumably in the temporary absence from HK of the Chief Justice himself for those periods. He never got the permanent appointment.