Here are a few more surprises from my recent visit to the UK's National Archives:

Naturalisation certificates, 1939-40

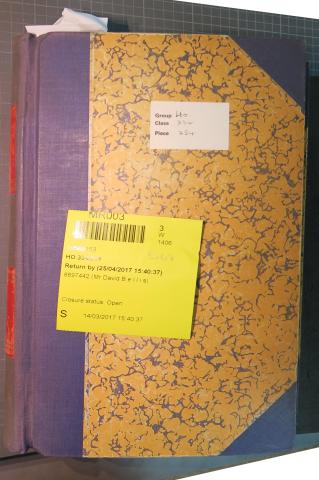

I'd asked to view what I thought was a single sheet of paper with details of a Mr Milenko, but instead I was handed this sizeable book [HO 334/254]:

It contains copies of 500 naturalisation certificates received from around the British Empire in 1939 and 1940. Luckily the certificates from Hong Kong stand out in two ways, so it's easy to flick through the pages and spot them. First they're printed on slightly smaller paper, so your finger feels when a Hong Kong certificate passes by. Second they're printed on blue-coloured paper, unlike the rest which are on standard white paper.

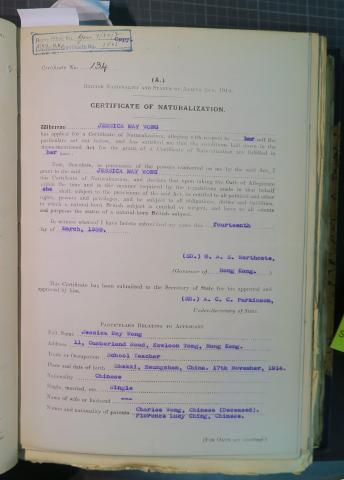

Here's the first one from Hong Kong:

It's the certificate for Ms Jessica May Wong, dated 14th March, 1939.

We learn that Jessica Wong was working as a school teacher, and living at 11, Cumberland Road in Kowloon Tong. Her father, Charles Wong, had died, but her mother Florence Lucy Ching was still alive. Jessica was aged 24, having been born in 1914 at Shekki, Heungshan in China. She swore her oath of allegiance the following week and became a British Citizen on the 20th of March, signing her name as Jessie M. Wong.

So the certificates are interesting from a couple of angles. First they give a glimpse of the person on that date, and also give details of their parents, which is invaluable information for anyone researching family history. But the cerificate also asks the question: why did this person want to change their country of citizenship? It's not a step to be taken lightly, so why did Jessica want to make the switch from Chinese to British citizenship?

The next certificate is for "Akwien Bertus Rudolf Tjon Kwie Sem commonly known as Edwin Tjon." As the long string of names suggests, he was born to parents from different countries. Unusually for the time, it was his father who was Chinese and his mother who was European. She was a Dutch woman, and Edwin was born in Dutch Guiana in 1910.

Next is the certificate for Florence Lucy Wong. If that name sounds familiar, it's because she was the mother of Jessica Wong, mentioned above. Florence was born in MacKay, Queensland, to father Charles Ching. "MacKay" and the family name "Ching" rang a bell, and sure enough Florence was the sister of Harry Ching, the SCMP editor whose diary of wartime Hong Kong has been so interesting to read.

Then I have to apologise - I was so busy flicking through the pages and clicking the camera's shutter, I didn't pay attention to whether the camera had focused or not. So several pages are too blurred to read clearly - a lesson to remember for my next visit.

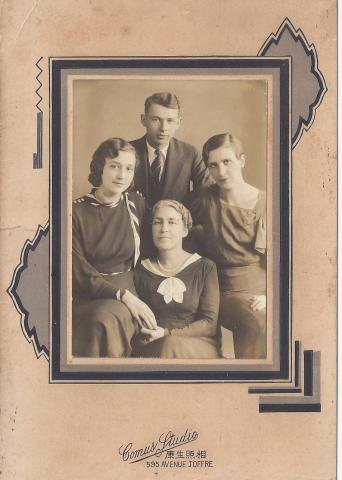

The next page in focus is another name I recognise, Vitaly Leonid Veriga, usually known as Vic. Here's a photo of him that Bob Tatz sent in previously:

Vic was living at 304 Nathan Road, and working as a Police Officer. His father and mother had Russian Nationality, but Vic was born in Kirin, North China in 1911, and gave his nationality as "No Nationality". In this case the attraction of British Citizenship was obvious, as Vic was stateless without a passport, which made for a precarious existence.

Many of the other men listed in this book have the same background: born to Russian parents but without any nationality of their own. Their family story often included flight from Russia after the revolution, living in Harbin and other cities in northern China, a spell in Shanghai, and eventually reaching Hong Kong.

Among these men, the largest group were Police Officers like Vic. They include:

- Vasily Alexandrovitch Elberg,

- Alexander Paul Zaremba,

- Fedor Longinovich Zadorin, and

- Constantin Petrovich Sherevera

The Russian community in Hong Kong was very diverse though, as shown by other certificates in the book:

- Nicholas Michael Kresnoperoff, Horse Trainer living at the Jockey Club Stables

- Mark Akimovitch Yaroogsky-Erooga, commonly known as Mark Akim, a registered Medical Practitioner living at the Queen Mary Hospital

- Vadim Bonch-Osmolovsky, commonly known as Vadim Bonch and working as an Electrical Engineer at Kowloon Docks

- Boris Georgievich Milenko, working as an Electrical Engineer and living at 377, Nathan Road

The best known of the group is a man who became a British Citizen on the 1st of July, 1940: Solomon Matveevich Bard, better known as Solomon Matthew Bard.

These certificates are the start of many interesting stories. On a future visit I'll photograph it again to get a sharper copy.

|

Help spread the word If you have friends who are interested in old Hong Kong, please could you forward a copy of this newsletter to them? At the bottom of every newsletter you'll also find buttons to share it on Facebook, Twitter, etc. |

The visit to the archives wasn't all about unexpected surprises. Some of the hoped-for information was also good to read:

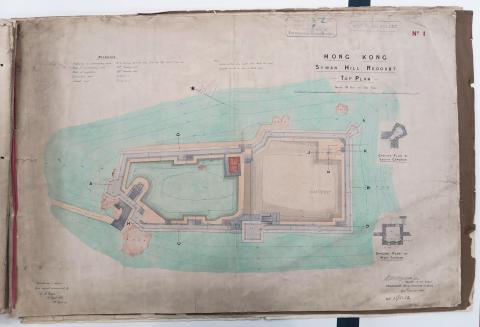

The original Saiwan Hill Redoubt

Back in December we visited the old Saiwan Hill Redoubt, and as we walked around the walls we saw this staircase leading up to what looked like the old entrance:

It's all blocked up now, as at some point the redoubt had been converted into a water reservoir. I was curious to know what it looked like originally, so thank you to Stephen Davies who gave me the National Archives reference for a plan of the site [WO 78/5352]. Here's how it looked in 1895, shown with its old spelling "Sywan Hill Redoubt":

The steps and arch in the modern photo are coloured dark-gray in the bottom left corner of the plan. They're shown at the head of "Footpath from Lyemun", and were the only entrance to the redoubt at that time.

The rusty iron tank above HKU

I also hoped to find information that would confirm the early use of cast iron water tanks in Hong Kong, and also tell us when the tank above HKU might have been installed.

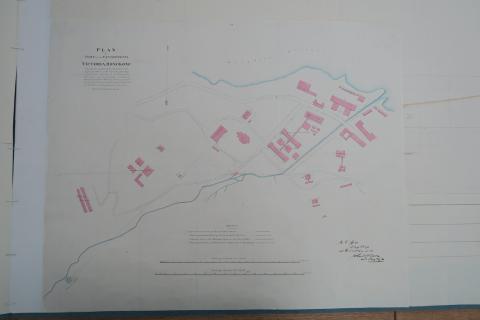

A search for Hong Kong water tank surprisingly turned up something useful, an 1850 map [MFQ 1/962/7] showing cast iron water tanks on military land:

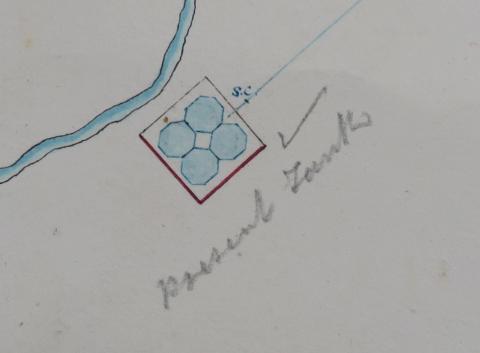

The key says "Present cast iron Tanks and Water Pipes . . . . coloured blue". They're in the bottom left corner. Here's a close-up, showing they are octagonal, just like the tank at HKU:

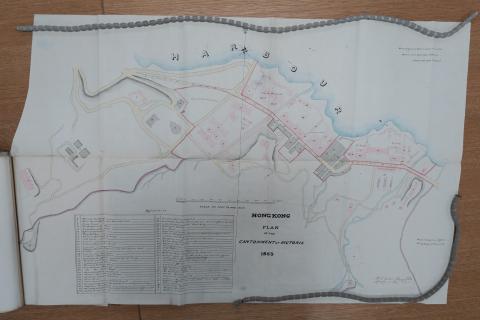

Another set of documents [WO 55/2962] includes this Plan of the Cantonment drawn in 1853:

The four tanks mentioned above are shown, so they were still around in 1853. AND, down in the bottom-right corner is another set of four tanks built to the same design!

So that's plenty of evidence that eight-sided cast-iron water tanks were used in Hong Kong's early colonial years. Next, when was the tank installed at the HKU site?

A detailed plan of the University site from 1910 [MPG 1/1209/2] confirms the tank hadn't been built then:

All the clues point to it having been erected sometime during the late 1920s / 1930s. While I was away, Moddsey and StephenD discussed the water shortages in Hong Kong around that time, which led to additional water tanks being erected. That is currently our best guess for when and why the tank above HKU was erected.

I hope you've enjoyed this virtual visit to the National Archives (if you missed part 1 last week, you can click here to read it).

When you're next in London they're well worth a visit in person, or if you're in Hong Kong you can head along to our local archives at the Public Records Office in Kwun Tong. Please let us know what surprises you find!

|

Readers ask for information (photos, facts, memories, etc.) about:

New on Gwulo.com this week:

|

Comments

Jessica & Florence Wong

Jessica and Florence along with Freddie, Charlie, Dickie (Jessica 's brothers) as well as her older sister were well known to the Guest family.

The Wong family eventually settled in Bondi, Australia.

Interesting Times

Those were the days a British Naturalisation Certificate meant something......

Boris Milenko

Hi David,

How amazing that you found these records - it seemed likely that they may not have survived the war. Guessing that the comment about fuzzy photos includes the one of my father, Boris - if it is not too fuzzy, I am still interested in seeing a copy.

re: Boris Milenko

Hi Michael, I've made a page for your father at https://gwulo.com/node/37460 under your account, so you can edit it to make any corrections / add any information. If you can add any detail about his time in Hong Kong, we'll enjoy reading it.

re: Jessica & Florence Wong

Henry Ching replied with more information about his cousin, aunt, and their family:

Jessica May Wong was my first cousin. She, her mother and siblings, were Eurasians. Her mother, a sister and three brothers were all born in Australia, but Jessica (the youngest) was born in China. So while the others were British by birth, she was not and so applied for naturalisation. This created rather a problem after the surrender of Hong Kong. Her mother and siblings were issued by the Japanese with Third National Passes, like the vast majority of Eurasians in Hong Kong who were not interned. But Jessica was refused. and was issued with an Enemy Pass, being naturalised British But she was not interned – the Japanese had no wish to intern (and house and feed) more than necessary.

From your post I discovered, however, something that puzzles. Her mother, my Aunt Flo, had also obtained a certificate of naturalisation. As she was born in Australia, she was already a British subject, so I don’t know why this was thought necessary. I guess it may have had something to do with her husband being a Chinese national. She may have been advised to do so because the Japanese were known to maintain that married women took the nationality of their husbands.

Aunt Flo and her two daughters served in the Auxiliary Nursing Service in December, 1941. Aunt Flo was at the relief hospital located in the stands at the Happy Valley race course, while Jessica was in the relief hospital in La Salle College in Kowloon. Florrie, the other daughter, was at the St. Paul’s relief hospital – this may have been in the St Paul’s Convent and Hospital in Causeway Bay, but I think it was in St.Paul’s College, next to Bishop’s House, in Glenealy but have not been able to verify this.

After the war, Aunt Flo and the two girls settled in Sydney, and lived in Bondi Beach. Charlie continued in Hong Kong and worked as a sub-editor for the South China Morning Post until he retired, some time in the 1970s I think. He then went to live in the home in Bondi Beach but passed away shortly afterwards. Freddie also worked for the SCMP, as accountant and later as Company Secretary. He also has passed away, but he left a widow (Patricia Taylor), a son and two daughters, now living in England and Canada. Dickie died in April, 1944 and is buried in the Colonial Cemetery.