Paul Braga

Businessman and fine arts collector

Paul Braga was the eleventh of thirteen children, and the ninth and youngest son of José Pedro and Olive Pauline Braga. Like his father and all his brothers, Paul was educated at St Joseph’s College, where he was a keen member of the 1st Hong Kong (St Joseph’s College) Scout Troop, and excelled as an athlete.

Physical fitness remained a lifelong interest. Paul reached adult years after the rest of his brothers, and by the time he left school in 1927, the family had moved to Knutsford Terrace, Kowloon, with most of his brothers and sisters still living at home.

Paul, chest expanded, standing next to his elder brother, Patrol Leader Tony Braga.

The Scout Master, seated, is his brother Hugh.

Two photographs from the album of his brother Hugh:

The motor age had arrived with greater prosperity in the colony, and Paul soon had a motor-bike. He soon found an opening in the motor industry, first in selling second-hand cars, trading as Paul Braga Motor Sales, Cameron Rd, Kowloon [1]. In April 1936 he joined Gilman Motors, becoming Manager of the Motor Department [2]. He stayed with the firm until the fall of Hong Kong in December 1941. With a pleasant and outgoing personality, he did well and developed good business contacts. He gained a lasting reputation for reliability and probity.

It was possibly for sale by Paul Braga Motor Sales, ca. 1934.

In January 1937 he married Audrey Frances Winsel, a vivacious, outgoing local girl of 22 whose flair and exuberance matched Paul’s. They were an ideal couple, and by the outbreak of war, they had two children, Frances and Paul Anthony (known as ‘Peter’). They had a house on Braga Circuit, recently developed by Paul’s father, who was Managing Director of Hongkong Engineering and Construction Co.

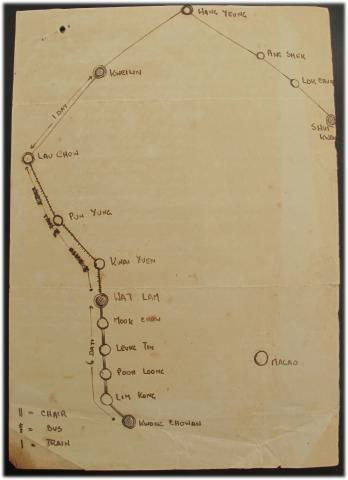

Paul, Audrey and the children were among the thousands caught up in the catastrophe of war, but, like other members of the Braga family, were able to claim Portuguese nationality, and soon made their way to neutral Macau, living in a house on the Praya Grande, a pleasant waterfront district. Paul soon perceived that the overcrowded, wretched conditions in the Portuguese colony were unendurable and decided to make a break for Free China. He hoped to make contact with his brothers Hugh in Australia and James in America in case they could assist the Braga family in dire straits in Macau [3]. In an epic journey which he carefully documented, he and his family made their way from Macau to Kweilin [4].

Here he became Manager of the Red Cross Club until Kweilin was evacuated, as Japanese forces approached. During the months they were in Kweilin their second son, Joseph Peter (‘Joey’ in the family) was born in Kweilin on 27 December 1943. Kweilin, threatened by the advancing Japanese Army, was a difficult and uncertain place for a European fugitive. At the end of the war, he told his brother Jack, ‘the months that followed were days of anxiousness and worry ... there were many many times when we regretted with all our hearts that that we ever left Macao’ [5]. Eventually they reached Chongqing (Chungking), the temporary capital of Nationalist China.

After a long delay, they were able to fly out of China, over the ‘Hump’ to Calcutta. By July 1945 they had made their way to Los Angeles, where Paul hoped to be an agent for an American interested in trading opportunities in the Far East after the war. However this did not eventuate and Paul and his family returned to Hong Kong, living in Kowloon Tong, a good residential area in North Kowloon.

Again he obtained a position in the motor industry, joining Dodwell Motors, although for some time there were few private vehicles on the road. Recovery took longer than most people expected, because the economy of Hong Kong had all but collapsed during the Japanese occupation. Eventually he became General Manager of Dodwell’s, and as prosperity returned in the following 25 years, the firm did well under his capable management. He retired in June 1970.

A family tragedy in the early 1950s severely affected Paul for the rest of his life, but Paul’s reaction to and handling of it were wholly admirable. Audrey suffered from severe headaches for some years, and local doctors were unable to help. Ready to do the best for his wife, Paul arranged brain surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, in 1955. In those days, such a procedure was innovative and hazardous. Sadly, it left Audrey with severely impaired capabilities and a greatly altered personality. Over time, she partially recovered to find fulfilment in Chinese painting. Her accomplishments, warmly supported by Paul, led to several excellent exhibitions and the enthusiastic endorsement of Dr Norman Vincent Peale, a famed Christian leader. In the long years of her illness, Paul was kind, compassionate, loyal and considerate. No husband could have done more than he did for a wife so changed.

Respected and successful in the Hong Kong business community as prosperity returned and the motor trade boomed, Paul developed an interest in collecting antique Chinese snuff bottles. He became a leading member of a circle of collectors and published two authoritative papers in the journal Arts and Asia [6].

In this he was assisted by his brother Jack, who from 1968 to 1972 was a consultant at the National Library of Australia. Intrigued by Paul’s request for information, Jack sent him useful material from his own substantial library and from contacts at the Australian National University [7]. Paul also developed a collection of pictures of early Hong Kong and Macau.

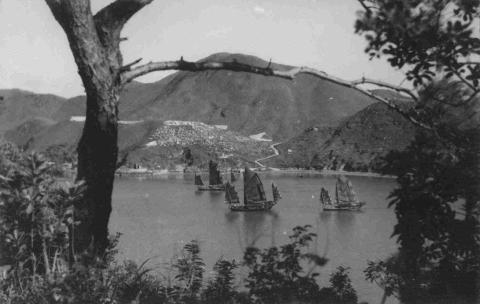

In the early 1960s, Paul developed with his brother Tony, also a capable businessman, a block of flats at Pokfulam, on the southern side of Hong Kong Island. Quite close to a major cemetery, the area had been shunned by Chinese developers until that time. His apartment had a magnificent view across Lamma Island to the South China Sea. Here Paul enjoyed photography, taking some fine studies of the view that was ever changing with the seasons, the weather and the constant flow of shipping.

Paul adapted well to the changing scenes of life. After his retirement, he relocated to San Francisco, where his daughter Fran and son Peter lived. Here, too, Audrey was in better care than in Hong Kong and long-term provision could be made.

His roots in the Far East remained with him in his aesthetic tastes, particularly in his fine collection of snuff bottles. He described this as ‘my principal interest in life’ [8]. The collection was carefully arranged in a superb cabinet and complemented by excellent pictures and furniture [9]. In the early 1980s, Paul fell ill with cancer and died aged 79 on 14 August 1989, survived by Audrey who died aged 83 on 6 December 1997.

Paul’s early years were a time of promise and achievement, while in his middle years he bravely faced the turbulence of war and the stress of his wife’s serious illness, but his later years were serene and contented. In his interests and collections, he selected only the best. It was a natural reflection of the quality of the man himself.

Stuart Braga, nephew, with minor corrections by Fran Rufener and Joey Braga.

19 November 2008. References added, 29 May 2009. Illustrations added, 5 November 2020.

Sources:

- Paul Braga papers, now in the Stuart Braga Papers, State Library of New South Wales, Series 24.9.

- Arts of Asia Vol. 6 No. 6, Nov-Dec 1976. Paul Braga, ‘Hong Kong Chinese Snuff Bottle Collectors’

- Arts of Asia Vol. 13 No. 5, Sep-Oct 1983. Paul Braga, ‘San Francisco Chinese Snuff Bottle Collectors, Part 1, The progress of a new group’, pp. 107-113; Part 2, Useful advice for the novice’, pp. 114-116.

- Urban Council, Hong Kong, Chinese Snuff Bottles, October 1977.

Paul’s experiences in the fall of Hong Kong

The five days from 8 to 11 December 1941 remained vivid in Paul’s memory for the rest of his life. He wrote at length to his brother James about this period soon after he reached Free China in 1943 [10 ].

I was an officer in the Auxiliary Transport Service and received instructions at six o’clock on the morning of the out-break to set up the station in the fastest time ... Aud. [his wife Audrey] appeared shortly and I had to leave them to report for duty, - saying good-bye was certainly the hardest experience of my life up till then.

He and another officer soon had the station going, but Paul later explained:

Almost from the outset it became evident that the A.T.S. was unable to give the required support to the fighting forces, owing to the strong “Fifth Columnist” activities from our own men.11

It was an early example of the desertion and acts of minor sabotage that would hamper the defence of Hong Kong in the next fortnight. With the collapse of the British position in Kowloon on 11 December, Paul too was cut off. ‘Everything was over in Kowloon before we knew where we were’, he wrote to James. His unit stranded, its personnel melted into the civilian population.

In May 1970 he told Wendy Barnes, a radio journalist, that he too changed into civilian clothes. ‘What happened to your uniform?’ he was asked. ‘I buried it’, he replied [12]. He buried his British identity along with it. Some time later, a Japanese officer appeared at Paul’s house, 4 Braga Circuit. He had a little written English, and wrote neatly on the back cover of a copy of the August 1941 issue of Good Housekeeping a demand that Paul hand over his house: ‘Japan great soldier come here tomorrow morning sleeping this house from there ago house.’ This message appears to mean: ‘The soldiers of Great Japan will come here tomorrow morning and will be sleeping in this house. [You will] go from the house.’ Paul wrote in reply. ‘This one Portuguese house’ [13].

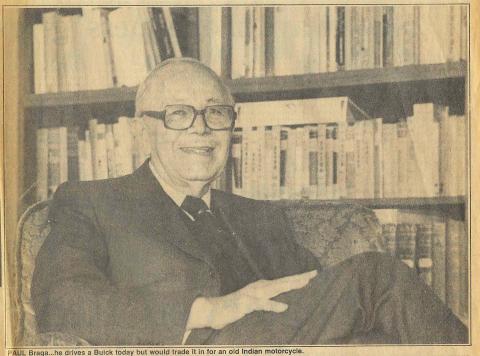

Late in life, Paul gave an interview to Kevin Sinclair of the Hong Kong Standard about his wartime reminiscences. Published with the headline “Secret lay buried in the garden”, it recounted the story, with a recent photograph of Paul [14].

Series 24.9, Folder 9.

The caption reads, “Paul Braga. He drives a Buick today but would trade it for an old Indian motorcycle.” The Buick was a premium General Motors automobile marque. It was a luxury vehicle positioned above GM's mainstream brands, while below the flagship Cadillac.

References:

- Letterhead of a letter from Paul to his brother Jack, ca June 1935, J.M. Braga Papers, National Library of Australia, MS4300, series 4.1.

- Reference for a former employee written during 1942, Paul Braga Papers, given to Stuart Braga by Joey Braga, 2001.

- Paul Braga to Jack Braga, 21 November 1945. J.M. Braga Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 4300, series 4.4.

- Paul Braga Papers.

- Paul Braga to Jack Braga, 21 November 1945. J.M. Braga Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 4300, series 4.4.

- Copies held by Stuart Braga, 2008.

- J.M. Braga Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 4300, series 3.9.

- Paul Braga, ‘San Francisco Chinese Snuff Bottle Collectors, Part 1’, Arts of Asia, Vol. 13, No. 5, Sep-Oct 1983. p. 110.

- Paul was a member of the Hong Kong Chinese Snuff Bottle Collectors Study Group, and was a contributor to an exhibition of three hundred snuff bottles jointly presented by the Group and the Urban Council, Hong Kong, in October 1977. The well-illustrated catalogue was in this writer’s collection at the time of writing.

- Paul Braga to James Braga, 22 October 1943. James Braga Papers, National Library of Australia.

- Paul Braga to J.A. Taylor (a business associate), 12 September 1943. Paul Braga Papers.

- A CD of the tape-recorded interview was made available by Paul’s daughter, Frances Rufener.

- He kept the page as a relic of this critical moment. Paul Braga papers.

- Hong Kong Standard, 27 December 1986. Stuart Braga Papers, State Library of New South Wales, Series 24.9, Folder 9.