Jean Pauline Braga

Born, Hong Kong, 23 June 1896; died, Hong Kong, 1 February 1987, aged 90.

Musician and music teacher

Jean Braga was the eldest of thirteen children of José Pedro and Olive Pauline (née Pollard). Born in Hong Kong, she attended the Italian Convent, conducted by the Canossian Sisters, where she became dux of the school. According to family tradition, she was to have been awarded a scholarship for further study overseas, but the scholarship was awarded to another girl instead. Surviving letters show Jean to have been, like other family members, sensitive and fluent in prose and verse. She was brought up in the environment of her mother’s conspicuous musical talent, becoming a capable violinist and pianist. She was vivacious and charming and was sought after as a music teacher. She became an accomplished horsewoman at a time when motor vehicles were few, and access to the family home at Robinson Road on the Hong Kong Mid-Levels was difficult. She was a woman of promise – good at everything to which she turned her hand. Three of the four Braga sisters, Jean, Caroline and Mary, became music teachers. It has been claimed that Jean was the best of them.

Jean was similar in personality and attainments to her mother as a young woman. She was a born teacher, and besides teaching the violin, also taught English at Ying Wah Girls’ School, run by the London Missionary Society near the family home. When the family moved to Kowloon in the 1920s, she taught English and Music at St Stephen’s Girls’ School.

She was also a born linguist, and was one of the few members of the family to speak Portuguese fluently – Jack and Maude being the others. For years, she was her father’s companion at official functions; as a member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council from 1929 to 1937, he had a significant public role. Jean, poised and elegant, was perfect on these occasions.

holiday to Shanghai, about 1925

From an early age, Jean gave her mother great assistance both in her music teaching and in the enormous demands of raising a large family. Although only 21, she was a tower of strength to her mother when her younger brother Chappie died in October 1917. Olive wrote to her sister Corunna, ‘Jean came with love to my rescue. She with such brightness and glowing love came like an angel.’ Olive later wrote, in a letter to her youngest son Paul in 1943, of Jean’s ‘extraordinary love for teaching and her wonderful aptitude in fashioning clothes.’ Olive experienced thirteen births and at least three miscarriages in the twenty years from 1895 to 1914. She grew old and tired before her time, worn out by constant poverty, incessant pregnancy, loneliness and the wearying demands of small children. Much of the burden of raising this large brood fell upon Jean. The family was far from well off throughout this time; there was the constant worry of making ends meet and feeding extra mouths. Clothes had to be constantly mended and altered for handing down. The discipline, too, of the younger children fell largely to Jean. It was a very similar situation in some ways to the manner in which Olive herself had been brought up by her elder sisters. Her mother, Mary Eleanor Pollard, had died in 1873 of cancer of the womb following the birth of fourteen children in seventeen years. Olive, the youngest, was three years old when her mother died, and she was cared for by her elder sisters and by her aunt, Corunna Weippert, who soon became her stepmother. A similar pattern was then repeated in the next generation.

Her younger siblings’ memories of Jean’s household management were not always happy ones, though in later life they could laugh about it. Jean enthusiastically embraced supposed ‘health’ diets, the most extreme being a lecture by a visiting nutritionist/faith healer who convinced Jean that one chicken liver was equivalent in nutritional value to a whole chicken. For a time, her younger brothers, ravenously hungry, were given half a chicken liver each for dinner, and sent to school next day with a slice of bread and dripping for lunch. Another memory is of being shut in a dark room for misbehaviour. The picture is one of excessive expectation of a young woman who had little time to live her own life. Small wonder that only one of Olive’s four daughters, Maude, married, and she remained childless. Indeed, it is remarkable that Olive and her daughter Jean retained their love of and commitment to music, especially the violin.

Jean remained unswervingly loyal to her mother and her family. She continued to live and teach in the family home on the Mid-Levels on Hong Kong Island, 37 Robinson Rd, and moved to Knutsford Terrace, Kowloon, with the rest of the family in the early 1920s. She paid for the education of her two youngest sisters, Caroline and Mary, respectively fifteen and eighteen years younger than herself, and for a year paid the university fees for her brother Hugh. She contributed to the weekly family budget. Later, she became her mother’s principal carer during the 1930s, as Olive now saw herself, and was seen by her family, now adult and more caring, as an invalid.

A former pupil, Barbara Anslow recalled more than eighty years later, “In 1927-1929 I had piano lessons from Jean Braga, and my elder sister had violin lessons, in the Braga family house in Knutsford Terrace, Kowloon. We didn't enjoy the lessons, but we LOVED going to that house which had a garden in front where we were allowed to play until ‘Miss Braga’ was ready for us.” [1]

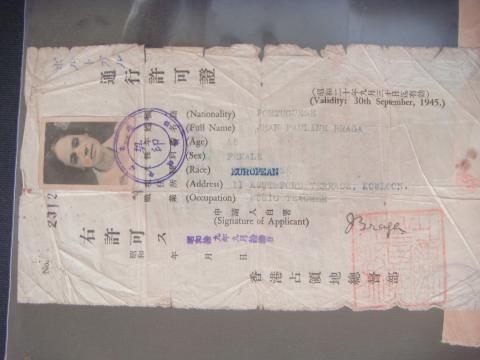

It was Jean who remained steadfastly at her post when Hong Kong fell to the Japanese in 1941. When the others escaped to Macau, she and Tony looked after the Knutsford Terrace properties. In the last 15 months or so of the war, when Tony, in danger because he had been a member of the Hong Kong Volunteers, also went to Macau, Jean held the fort alone: a courageous – indeed heroic – stand.

Jean was pleased to be alone, free at last of her mother’s constant presence and insistent demands. Her mother wrote to say that it broke her up to think of Jean living on in the big family home. Jean replied with a blast. ‘Why should you worry on my account, when I do not?’ The obvious reason for staying in Hong Kong was that ‘I can’t bear to see these houses ruthlessly looted.’ However, there was far more to it than that. She had discovered independence.

About “peace” – this is attained when one can go ahead doing one’s best without hindrances. Up till now, I have enjoyed a quiet and peace that electricity & water & other comforts cannot give. Here I rise with the dawn, finish my housework before 10 am, & can go about my business without upsetting the habits & time tables of others & their feelings too. This year my health has never been so good, because thinking and acting for myself have made me strong. Food has never tasted so good, because my appetite has never been so keen. Work has never been so pleasant, because there has never been anyone to find fault. Sleep has never been so sound, because I have never been so tired. Real friends have never been so loyal, because they have been tried and not found wanting. Pleasures like playing on the grand piano & gardening have never been so enjoyable, because I can now spare the time for them. My music upsets no-one’s nerves and even singing (or is it screeching?) is music to me & who else cares? [2]

It was the clearest of statements that Jean was determined never again to be under her mother’s powerful thumb. In fact she too knew real hardship right through the war, holding the fort at Knutsford Terrace. She had a few pupils still, but survived by breeding and selling rabbits and by selling the fruit of a large mulberry tree. The Japanese soldiers liked fresh mulberries, and the fruit brought in enough money to eke out a bare living until the next crop.

At the end of the war, Jean refused to have her mother back to her home in Knutsford Terrace. She had become obdurate during this long ordeal, but was seen to be even more so. “One has to admire her courage’, wrote her sister-in-law Nora, ‘in the way she carried on alone all through the war, but, according to Maude, it has embittered her and she is more difficult than ever.” [3] Nevertheless Caroline saw another side to Jean.

When the troops landed in Hong Kong, the R.A.F. took over Royal Court Hotel at the end of the Terrace and Jean became their mascot ... when the R.A.F. saw her they were touched with pity and plied her with good food and she writes to say how happy she is with them. She has her grand piano and when they have time off they go to the house to sing while she accompanies; and altogether she is feeling better and happy. [4]

One of the young airmen who were sent to garrison Hong Kong, Ken Wilkie, advertised in the Forces newspaper for a piano teacher. Jean answered it, and his visits for lessons led to a lasting friendship with Jack’s family when they returned to Hong Kong early in 1946 and lived at Knutsford Terrace. [5]

Jean, once accomplished and vivacious, was affected by the war more than others. She had witnessed many atrocities at first hand. After the war, she became a withdrawn and difficult person, and eventually a recluse, jealously guarding her possessions and furniture. She could fly into rages. The experiences of a hard life, and most of all the privations, loneliness and constant fear in the face of hostile Japanese soldiers had eaten into her.

Jean continued to teach music, still with a remarkable ability to encourage and affirm her students, one of whom, Barbara Merchant, wrote,

I had a wonderful piano teacher called Miss Braga in HK between 1964 and 1967 … she was inspirational … she really made me feel gifted and special. She taught me twice a week for an hour each session, and I really enjoyed learning with her … she lived on Chatham Road, and she kept her furniture covered with dust sheets. [6]

This was the furniture that Jean had kept from looters throughout the war and now protected just as zealously, as though looters might still break in.

However, by the late 1960s, her great gifts began to leave her. She survived into old age, but the four decades after the liberation of Hong Kong in 1945 became a shadow land, blighted by the years of hardship, the bitterness of opportunity denied and a life unfulfilled. Jean Braga had selflessly and loyally given the best years of her life to the upbringing of her younger siblings. That most of them lived lives more enriched than hers is a tribute to her care and devotion.

Stuart Braga

11 November 1996, revised 7 December 1996, 19 March & 3 April 2001, 4 December 2010, 8 March 2013 and 15 April 2022. Illustrations added 15 April 2022.

References:

- hongkongwardiary, 4 December 2010.

- Jean Braga to Olive Braga, 14 December 1944. James Braga Papers.

- Nora Braga to James Braga, 25 January 1946, James Braga Papers.

- Caroline Braga to James Braga, 21 October 1945. James Braga Papers.

- Ken was still in touch with the Braga family as recently as July 2016, when Stuart and Patricia Braga stayed with Ken, then aged 89, at his elegant flat in Edinburgh. They were greeted warmly and entertained like royalty. Another, Edgar Greenwood, according to Tony, gave Jean half his salary each month because he felt sorry for her. Tony Braga to John Braga, 29 April 1946. James Braga Papers.

- Emails, 7 and 8 March 2013, from Barbara Merchant, UK, formerly of Kowloon, Hong Kong

Comments

St Stephen’s Girls School - photograph

It has been fascinating to read about the Braga family, particularly about Jack. A childhood pal of mine at Quarry Bay School was Joey Braga whom I am sure is part of the same family. The last I heard of him was that he was living in Australia.

The photograph of the staff at St Stephen’s Girls School is the same one that features on page 180 of that wonderful book entitled ‘Old Hong Kong’ by Trea Wiltshire. The lady in the light coloured suit in the front row is actually Miss Edna Atkins who took over from Miss Middleton-Smith as Headmistress. The picture on the opposite page (181) shows the two of them together in the staff sitting room with Edna seated on the left.

Edna, who was interned in Stanley, was my Godmother. She eventually retired to Winchester, England and, if my memory is correct, lived to 104. Throughout my life she never forgot my birthday or Christmas and even attended my confirmation at Truro Cathedral, Cornwall in the late 50’s. When Trea’s book was published circa 1986 I was working in the Hong Kong Government office in London and was given a copy. On seeing the photos of Edna, my wife and I took the book to show her. By that time she was well into her 90’s and her sight was beginning to deteriorate. Not on that day, however, as soon as we got to page 180 she immediately identified herself saying “That’s me!”

I still have the little book of prayer that she gave me when I was christened in Stanley camp on 8th October, 1944 as well as some water colours that she painted of camp scenes. A truly wonderful lady who was the best Godmother that anyone could wish for.

Keep up the good work David!