John Vincent Braga

Born, 5 Seymour Terrace, Hong Kong, 25 September 1908;

died, Edinburgh, 29 May 1981, aged 72.

Company Secretary and violinist. Owner of the Braga Stradivarius.

John Braga, named for his paternal great-grandfather, João Vicente Braga, was the tenth child and eighth son of José Pedro and Olive Pauline Braga. He was one of a group of six boys born between 1903 and 1910: Noel, Hugh, Tony, James, John and Paul. They were a family within a family, a group who stuck together closely as they grew up in Robinson Road, Hong Kong, then the Portuguese quarter. It later became known as the Mid-levels. The older members of this group of six tended to dominate the younger ones, and were the ring-leaders of the rough, tough gang of urchins who were often up to mischief. They were a boisterous lot, sometimes too much for their mother, but she took special care of the younger ones, who tended to be a bit on the outer, and were not as sports-minded.

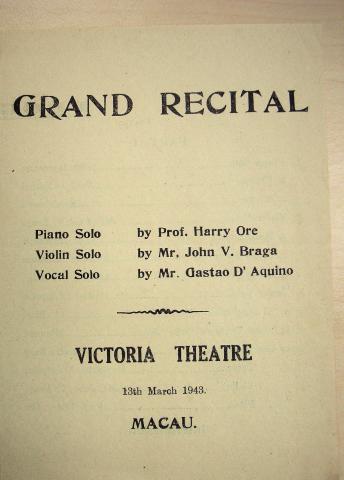

John responded to his mother’s care perhaps more than any of his brothers. She had been an outstanding violinist in youth – the cliché ‘child prodigy’ is apt in her case – and still played her treasured eighteenth century Amati violin, though mostly for the family. As they came home from school (John hated St Joseph’s College, where all the boys went), she would be seated at the piano and led them in singing. Here they imbibed something of her passion for music and her firm religious outlook. John, more than any of the other boys, shared his mother’s love of the violin, though a boyhood injury to his hand meant that he was never able to play the instrument with her degree of skill. However, over many years, he played, often with his younger sisters Caroline and Mary, in concerts and musicales in Hong Kong, both before and after the war and in Macau during the war.

On leaving school, he entered the employment of China Light and Power Company, where his elder brother Noel already worked. His musician’s neatness and thoroughness were an asset in a business environment. The later 1920s were years of rapid growth in the electricity business, and both John and Noel did well in this successful company. John became the assistant Company Secretary, in charge of the shares office.

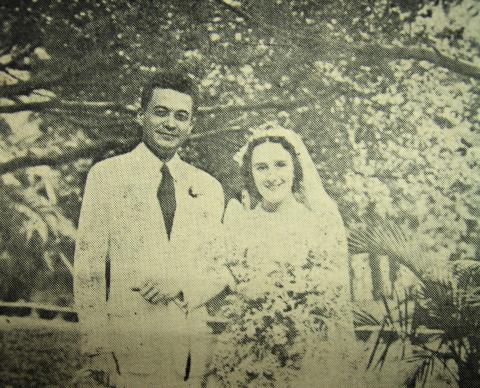

He travelled to Great Britain in the late 1930s, where he met Louisa Winifred Ashton, a gifted medical student at Edinburgh University. ‘Louie’ as she was always known, shone particularly in Anatomy, in which she had gained the highest marks ever awarded at Edinburgh. At the outbreak of war, Louie came to Hong Kong, intending to complete her medical degree in a more secure environment. John and Louie were married at St Andrew’s Church, Kowloon, on 24 August 1940, some weeks after the fall of France, and the subsequent Japanese occupation of French Indo-China, now Vietnam. Professor Gordon King, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Hong Kong University was the best man. However, Louie never completed her degree. The birth of her eldest daughter, Rosemary on 15 August 1941, and then the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, brought her studies to an end.

With most other members of the Braga family, John and Louie eventually fled to Macau after some months of peril in Hong Kong under Japanese occupation. Here they spent the remainder of the war, in security but in deprivation. A second daughter, Joan, was born in 1945, and the family went through hard times, with Louie suffering from beriberi, a disease brought about by malnutrition. However, both children survived the war. John earned a little money by playing the violin to Japanese troops until the family moved to Macau, and then by teaching the instrument, but it was not enough to live above starvation level.

From the papers of John’s sister Caroline Braga,

National Library of Australia

John, Louie and their children returned to Hong Kong after the war. Two more children were born to them in the next few years: David and Vivien. John returned to his old position at the company, then known as China Light and more recently as CLP, but things were never the same as they had been before the war. In the 1920s and 1930s, John had the Midas touch in business administration, but it seemed now to have deserted him. Like many others, he never really got over the war: the years of hardship and privation robbed him of his drive. Louie urged him to complete his qualifications in Accountancy as his brother Tony did, but he never finished the course.

Moreover, the climate changed in China Light in these years. Before the war, there was a consideration and mutual respect between British officials and businessmen on the one hand and local people of Portuguese descent on the other. After the war, a new managerial set came out from Britain who lacked the old understandings. John was seen as a member of the local Portuguese community who were routinely belittled and he was not treated well at China Light in the post-war period, though he was a Protestant, had a Scottish wife, and possessed considerable skills in written and spoken English.

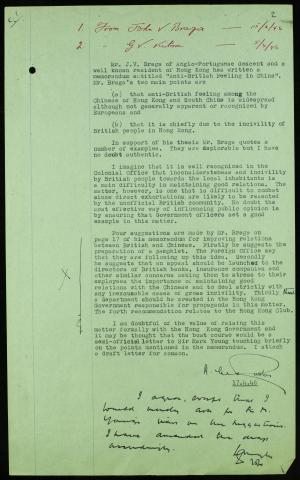

In February 1946, still in Britain, he wrote a lengthy memorandum entitled “Anti-British Feeling in China” to the Colonial Office in London, complaining about the situation [1]. This received considerable attention in both the Colonial Office and the Foreign Office, a copy being sent for his comment to Sir Mark Young, who was about to return to Hong Kong as Governor following his incarceration by the Japanese from Christmas Day 1941 until the end of the war. However, John’s main suggestion that a pamphlet should be produced to brief public servants going to Hong Kong does not appear to have been acted on. British arrogance continued to characterise race relations until the serious riots of 1967.

(Miss A. Ruston to Mr G.V. Kitson, 17 April 1946).

His terms of employment were indeed those of an expatriate, and in 1950, he was eligible for nine months’ leave after four years of service. John and Louie returned to Edinburgh with the children and bought a house there. Louie stayed on in Scotland, while John returned to Hong Kong alone for a time until the family joined him in 1952. He stayed on at China Light until 1966, when he retired somewhat early aged 58. These continued to be unhappy years, the more so because John believed that his immediate superior was corrupt but was powerless to do anything about it.

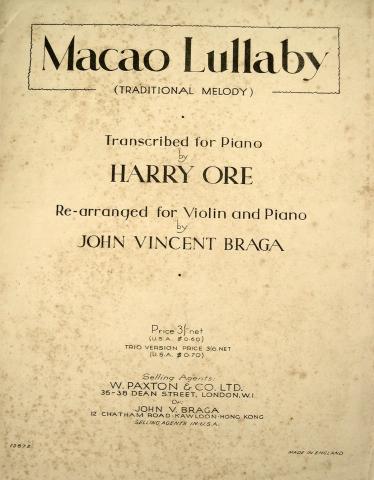

In these difficult times, the violin was John’s solace, even more than it had been in earlier years. He had written during the war a sensitive and moving arrangement for piano and violin of a traditional piece called the ‘Macao Lullaby’. It was widely known; indeed, at the 3rd Encontro of the scattered Macanese people, held in Macau in March 1999, many of those present at the final reception emotionally joined in singing it when it was played by a string ensemble. It had become almost a ‘leitmotif’ of Macanese identity.

From the papers of John’s sister Caroline Braga,

National Library of Australia

The violin was John’s chief interest in retirement. He wrote more music for it, but his chief talent was a remarkable ability to ferret out old violins made by Italian and Spanish masters, especially those from the golden age of Italian violin making in Cremona in the 18th century. He went to Spain several times in the 1950s and 1960s and struck up a friendship with the leading violin maker Fernando Solar Gonzalez. This was at a time when, before the tourist boom of the last quarter of the twentieth century, Spain was an impoverished country, still prostrate after the ruinous civil war of 1936 to 1939. There were many old violins to be found in churches as well as private homes. Together Braga and Gonzalez discovered a number of significant old Italian violins in Spain, and John also travelled to southern Germany and to Cremona in Italy.

He had purchased his own Stradivarius violin quite cheaply from the English dealer, Hill, in the early 1950s, before the value and scarcity of these famous instruments was fully recognised. John had it for some years but sold it for £5,000 in the early 1960s [2].

Perhaps John Braga should have been a violin dealer in his later years. Certainly, it was a field in which he had outstanding expertise, and he had a knack for picking a genuinely rare and important instrument. His years of experience in a senior position at an early age in China Light had helped him to become a good judge of character, and he was, like most of his family, an excellent letter writer. These skills in a robust man would have fitted him for a senior administrative position. Instead, his later years were dogged by increasing ill health. He suffered a mild stroke in 1974 at the comparatively early age of 66, and was thereafter an invalid. He died in 1981, not long after visiting his daughter Rose in Australia.

In his arrangement of the lovely ‘Macao Lullaby’, full of peace and joy, yet written at a time of hardship in the midst of war, John Braga left a legacy of enduring value to the Macanese people. He was survived by his wife Louie, who lived for many years in Edinburgh, then moving in 1996 to Sydney, where she was given devoted care by her daughter Rose. She died aged 86 on 19 April 2005, the last surviving member of her generation of the Braga family.

David Braga (son) and Stuart Braga (nephew)

20 April 1999, revised 16 May 2005, 5 May 2008 and 13 February 2025.

References:

- CO 129/595/1. A copy is in the Hong Kong Public Record Office.

- This detail was recounted by John’s son David, who pointed out that it is in the list of Stradivari instruments with the sobriquet ‘Braga Stradivarius’. David said that it was possibly experimental as it was an unusually large violin. This is indeed the case, but the instrument, made in 1731, is listed as a cello. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Stradivarius_instruments accessed 12 February 2025.