José Maria (‘Jack’) Braga

Born, Hong Kong, 22 May 1897; died, San Francisco, 27 April 1988, aged 90.

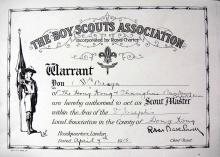

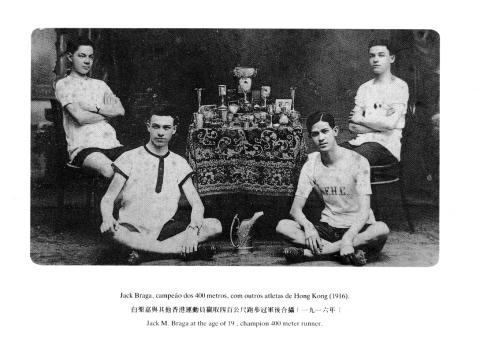

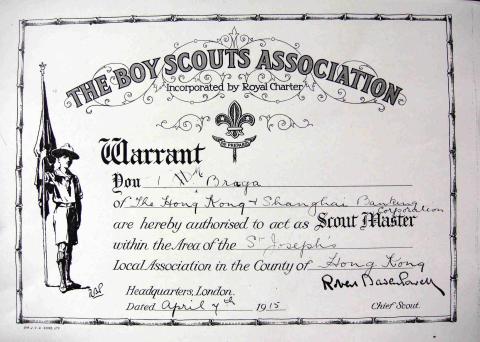

Jack Braga was the second of thirteen children, and the eldest of nine sons of José Pedro Braga and his wife, the Australian-born Olive Pauline (née Pollard). He was educated at St Joseph’s College, Hong Kong from 1908 to 1913, passing the Oxford Senior Local in his last year. He was a keen athlete and personal fitness meant much to him. Like many young men in the Portuguese community, he then gained employment in the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. He joined the Boy Scouts as soon as it commenced in Hong Kong in 1913, and when the British scoutmaster left in 1915 to go to the war, Jack succeeded him at the remarkably early age of 18.

St Joseph’s College, 15 March 1915.

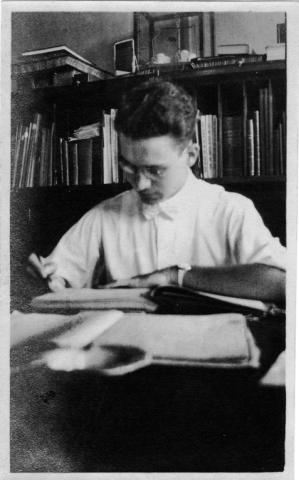

Jack had a love of books from early years. In September 1921, his youngest brother Paul went round the house with a camera, photographing anyone who was around. Jack was at his desk.

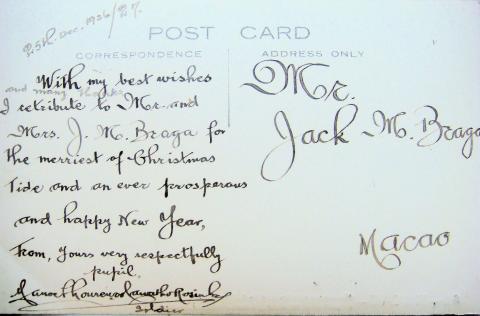

After World War I, Jack moved to Macau where he lived and worked from 1924 until 1946. He married Augusta Isabel da Luz (born 19 November 1898) in Macau on 30 December 1924. They had seven children. She died in San Francisco on 14 December 1991 aged 93. Jack alone retained the Catholicism of his upbringing, whereas all his twelve siblings left the Catholic Church.

by a ‘very respectfully pupil’.

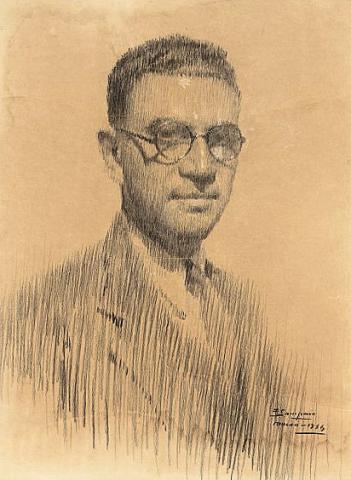

Soon after his arrival in Macau, Jack Braga became keenly interested in the history of the European encounter with East Asia from the 16th century until the mid-twentieth century. With remarkable persistence and assiduity he set about recording and collecting the history of Macau covering four centuries since the arrival of the first Portuguese voyagers in the early 16th century. As well as amassing a large library of books, maps, pictures, newspapers and manuscripts, he recorded the minutiae of the historical record in a detailed, meticulous and highly organised way. His method was to create a series of files and chronological lists covering the events, the people and the written record of these four centuries. There were two principal lists. The main one was a ‘General File’ or ‘Bio-bibliographical Index’, organised alphabetically, which grew to more than 11,000 entries, extending to two metres of shelf space. The called this his ‘A to Z’. The second was a ‘Luso-Oriental Manual’, a detailed list of the most significant Portuguese officials and missionaries in the Far East together with important State officers, chiefly in China, with whom they dealt between the 16th and early 20th centuries, concentrating on the era of Portugal’s dominance of trade and missionary activities in the 17th century. In 1937 he began a collaboration with Charles Boxer, a British army officer with similar interests. They became life-long and very close friends. Braga had been a prolific contributor of articles in English and Portuguese to the local press from the late 1920s, and the friendship with Boxer enriched his scholarship. Boxer described his friend as ‘the learned Macau antiquary’. [1] Later he would recognise him as an able historian.

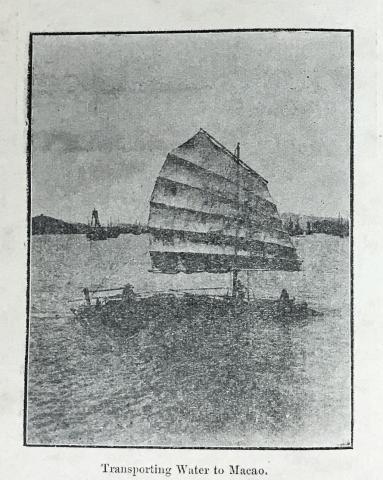

He taught English at St Joseph’s Seminary, Macau, until 1934, and from 1930 to 1932 also taught at the Liceu de Macau. [2] He taught the Commercial course of English, educating hundreds of youths who joined commercial firms in Macau, Hong Kong, Canton, Shanghai, Bangkok, Yokohama and Tokyo. [3] He played a major part in establishing in 1925 the first Macau daily newspaper Diario de Macau. He was the Reuters representative in Macau (1932-45) and the English editor of The Macao Review (1929-30), as well as being a contributor to other papers, such as A Patria, A Voz de Macao and Macao Tribune. [4] In 1929 he became involved in a major project in the small Portuguese territory, the Companhia das Águas de Macau (Macau Water Works Co., usually known as ‘Watco’). A private venture, this company proposed to supply town water to Macau, which until the 1930s had a completely inadequate water supply, with a very small catchment area, Guia hill. Macau therefore often relied on water brought in by lighter (a barge) from China.

J.M. Braga was effectively the company’s founder and became its General Manager. The plan was to build a retaining wall, enclosing a bay on the relatively undeveloped north-eastern coastline of Macau, which would then be used as water storage. A filtration plant was to be provided.

By 1934, the company was in a desperate financial predicament. It was without funds and salaries were unpaid. Jack, who himself had nothing from the company for several years, paid several workmen’s wages out of his own pocket. Large sums were owed to the Hongkong Engineering and Construction Co. (the Managing Director of which was his father) and other larger creditors. The Macau Government was not involved in the project, being itself in a difficult financial situation. The company went into liquidation, but after much effort and worry, was recapitalised, and the project was brought to completion in 1936, largely due to Jack Braga’s sustained commitment. [5]

The population of Macau was then fewer than 200,000. In 1938, a flood of refugees fled to Macau when Canton (Guangzhou) fell to the Japanese. A few years later, the population, swollen by refugees after the fall of Hong Kong in 1941, reached 500,000. Without an adequate water supply, Macau could not have coped with this emergency and refugees would have been turned away. Jack Braga effectively saved the lives of thousands of people. He remained General Manager throughout the war until 1946, when he moved to Hong Kong.

The outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941 led Jack to collect intensively as much of the printed record of wartime Macau as he could, and the result is a unique and detailed collection which he prized greatly. At the outbreak of war, there were few members of his family in Macau : Jack, Augusta, Jack’s brother Clement and his wife Muriel. Therefore, after the fall of Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941, Jack and Augusta’s role in their family was crucial. Over a period of two years, nine of the Bragas left in Hong Kong, including both of Jack’s parents, escaped to Macau, leaving only Jean, Jack’s elder sister. Another sister, Maude, who was married to an Englishman, was interned.

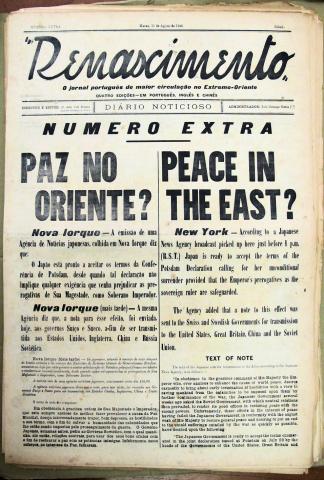

Jack’s activities in wartime Macau were diverse and extensive, and his accomplishments were quite amazing. He continued to write historical articles for the local press, often with an eye to boosting the morale of thousands of English-speaking refugees in Macau. He was instrumental in establishing the English edition of ‘Renascimento’, catering for the large refugee population.

He wrote a weekly article broadcast from June 1941 to December 1942 on the station operated by the Macao Radio Club, there being no government radio service. After the arrival of his father from Hong Kong in June 1942, he gave ‘JP’ much assistance in commencing the book he had intended to write for many years. Although incomplete when J.P. Braga died in February 1944, Jack had a small edition of only ten copies published immediately of the twelve completed chapters. As well as all this demanding work, Jack became active in Allied Intelligence activities, and on at least one occasion, his life was in danger. [6] He continued to be most active in community affairs, especially in setting up the Macau Technical College, a brave attempt to fill the void in higher education. In the last months of the war, he was a member of a group that prepared an emergency plan for Hong Kong should the Japanese kill all their prisoners at the end of the war and depart, leaving a starving population behind. [7] Many people who experienced nearly four years of hardship and inactivity in Macau between 1942 and 1945 never regained their former vigour. Although he and his family experienced severe privations like most others, Jack Braga never lost his vigour and strong community spirit.

For the next twenty years he lived and worked in Hong Kong, running a small import-export business, Braga & Co., though his friend Geoffrey Bonsall whimsically suggested that his book collection was really his business, absorbing most of his time and interest, while the business was his hobby. [8] His passion for book collecting and historical research dominated his time and interest. Residence in Hong Kong gave a new dimension to his collection, which now extended to the history of British activity in the Far East from the late 18th to the mid twentieth century. In addition, his determination to record the history of Portuguese expansion took a new turn, and he now added many transcriptions of important papers documenting the activities of early navigators and missionaries. In 1952 he visited Portugal, and embarked on a project of securing transcriptions of the important ‘Jesuitas na Asia’ manuscripts in the Ajuda Library, Lisbon. [9] He regarded these manuscripts as the most important part of his collection. [10]

By the early 1950s, his output became more selective, and the continuing collaboration with Boxer brought about a substantial improvement in his scholarship. Boxer sent him several manuscripts for comment, and dedicated one of his major works to his old friend. [11] Jack published in 1949 what would prove to be his magnum opus, The western pioneers and their discovery of Macao, Imprensa Nacional, Macao, 1949.

Imprensa Nacional, Macao, 1949.

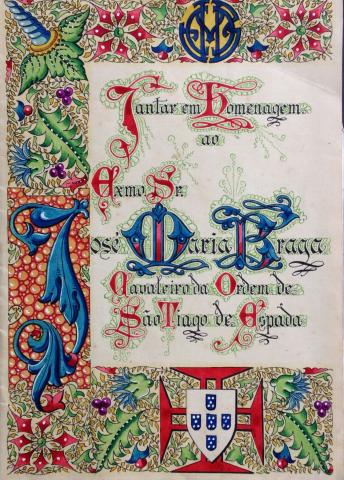

In addition, he produced several scholarly papers, notably The beginnings of printing at Macao, Lisbon, 1963 and A seller of sing-songs: a chapter in the foreign trade of China and Macao. [12] For several years he prepared an extensive bibliography for the Hong Kong Annual Report. His growing reputation led in 1949 to the award of Cavaleiro do Ordem do S. Tiago da Espada (Knight of the Order of St James of the Sword) by the President of Portugal. However, a proposal made by friends for Hong Kong University to award Braga an honorary MA was unsuccessful. [13]

During the early 1950s Jack came to realise that there was no long-term future for himself and his family in the Far East. [14] The Korean War had called into question the survival of Hong Kong as a British colony. However, he had first to see to his children’s education. He had not had the chance of a university education himself, and was determined to secure this opportunity for his children. For many years his father, J.P. Braga, had been a close business associate of the wealthy businessman Sir Robert Hotung, who out of regard for ‘JP’ and also for Jack, whose role in public affairs in war-time Macau had been most praiseworthy, now paid for three of J.M. Braga’s four daughters to attend Hong Kong University. In 1952, his three sons were sent to Sydney to complete their schooling, and two went on to graduate from the University of Sydney. Jack planned to follow them to Australia as soon as suitable arrangements could be made for his wife’s two unmarried sisters who were dependant on him, and for whom visas could not be obtained. He also hoped to obtain a position for himself that would enable him to work full-time in his beloved library.

From José Maria Braga, O Homem e sua obra [The Man and his work],

exposiçao realizada na Biblioteca do Leal Senado,

de 9 a 16 de Feveroiro de 1993

Political troubles in Hong Kong and Macau associated with the rise of the Chinese Red Guards in the mid-1960s hastened his decision, and in 1966, Jack sold his library to the National Library of Australia for £10,000 sterling. As a businessman, he had often pursued a mirage, and seeing others grow wealthy, hoped to do the same. An essentially kind and straight-forward man, he did not seem to realise that others took advantage of him. With what appeared to be a sizeable sum available to him for the first time in his life, he decided to go to New York to make a fortune. It was a disastrous decision, and he later admitted that it had been a mistake and a waste of time. [15] Within two years, the money had all gone. Only then did he come to Canberra to see what had happened to his books.

Another facet of the disaster was that his library, so precious to Jack, arrived in Australia without his supervision. The National Library of Australia, recently established in its fine new building, at first lacked qualified staff. The high rate of acquisition was not matched by the staff resources to deal with the collection adequately. By the time Jack eventually arrived more than two years later, he found an alarming situation. It was a major task to locate and organise his books, and the World War II collection, intended to be kept together, had been dispersed. He worked at the library as a consultant from October 1968 until February 1973, but his health was already failing. He set himself the task of translating into English the most important of the ‘Jesuitas na Asia’ manuscripts, Bishop António Gouveia’s ‘Asia Extrema’, hoping that it would be published by the National Library of Australia, but was able to finish only three of the six books.

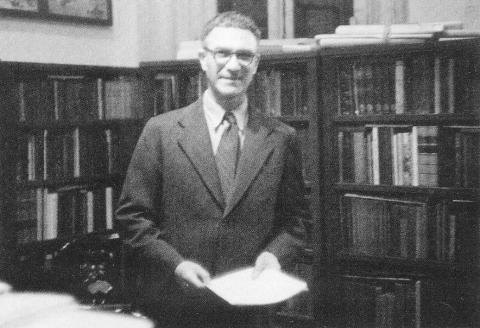

17 March 1969. [16]

The twilight years were sad and very prolonged. Afflicted by Parkinson’s disease, Jack went with Augusta early in 1973 to San Francisco, where their eldest daughter Carol, was Professor of Gynaecology at the University of California, Berkeley campus. She gave her parents devoted care until their deaths, 16 and 19 years later. By then, his name was held in honour in the little Portuguese colony that he had done so much to promote. He was awarded posthumously the high rank of Comendador, Ordem do Infante Dom Henrique [Commander of the Order of Prince Henry the Navigator].

Jack Braga was a remarkable man. He grew up in Hong Kong, a place of opportunity until the years immediately following World War I, when business conditions were bad and opportunities few. Macau, the sleepy backwater that his family had left eighty years before, then became his home for the next twenty-three years. Jack worked diligently as a teacher and as a businessman. He never had sufficient means to support his growing passion for books, pictures and maps. Yet he persisted, and despite all the setbacks caused by depression, war and business difficulties, he left a fine legacy – a collection of abiding value and usefulness to Australia, where most of his family had made their home. Moreover, he left behind him in the Far East a name that continued to be held in honour and respect several decades after he had left.

Stuart Braga

3 March 2008, revised and illustrations added 5 May 2022.

References:

- C.R. Boxer, Seventeenth Century Macau in contemporary documents and illustrations, p. 3 note.

- Autobiographical sketch, in Portuguese, prepared in 1970. National Library of Australia, MS 4300.

- P. Haldane, ‘The Portuguese in Asia and the Far East: the Braga Collection in the National Library of Australia’, A paper prepared for the Second International Conference on Indian Ocean Studies held in Perth, Western Australia, 5-12 December 1984.

- From notes by Graeme Powell, formerly Head, Manuscripts Branch, National Library of Australia.

- National Library of Australia MS 4300 series 4.2.

- Letter of appreciation to Jack from John P. Reeves, the British Consul, 24 July 1946. This refers to assistance given to American airmen shot down off Macau in January 1945, and brought to Macau by Chinese fishermen. MS 4300.

- MS 4300 series 8, folder 13.

- Obituary in Revista de Cultura.

- MS 4300 series 6.1.

- Pauline Haldane, op. cit.

- C.R. Boxer, South China in the sixteenth century, London, Hakluyt Society, 1953.

- Hong Kong University Press, 1967, reprinted from Journal of Oriental Studies, vol. 6 no. 1-2, 1961/64.

- Geoffrey Bonsall, the University’s Deputy Librarian, was a prime mover in this.

- National Library of Australia MS 4300 series 3.2. Letter to Fr Antόnio da Silva Rego.

- National Library of Australia MS 4300 Series 3.2, Letter to Fr Antόnio da Silva Rego.

- Canberra Times, Tuesday 18 March 1969, page 14:

Mr Freeth opens display

A valuable collection of Brazilian and Portuguese books, periodicals, maps and manuscripts are on display for the first time at the National Library. The Minister for External Affairs, Mr Freeth, opened the exhibition in the National Library Theatre last night. Its aim is to advertise that the historic collection is available for public use and to stimulate interest in Brazilian and Portuguese affairs. The library, which has been acquiring material in the exhibition from private collections over a number of years, is launching the display in association with the Brazilian and Portuguese Embassies. Mr Freeth said that although the works were essentially for research students he hoped that people would become more generally aware that the National Library had these collections.In recent years the library has acquired two significant private collections of materials of Brazilian and Portuguese interest. One is an eminent scholar’s collection of 12,000-odd volumes of books, monographs and other papers dealing with the literature, history, geography, economy and politics of that country.

The other [the J.M. Braga Collection] is of about 6,000 volumes concerned mainly with Portuguese exploration and discovery and includes manuscripts. newspapers, drawings, water colours and notes.Mr Freeth said Australia had a special and early connection with Portugal. “Indeed, it may eventually be proved that the Portuguese explorers were the discoverers of Australia. This library, in its quest for material, may well play some part in such a discovery by uncovering some diary, or ship’s log, which will give historians a chance to re-assess the claims,” he said.

The Australian mission at Rio de Janeiro, which dates back to 1945, is Australia’s oldest in Latin America, and the Brazilian Embassy was one of the pioneer missions in Canberra, having been established in 1946.

Mr Freeth added, “I am most conscious that any activity by which nations learn more of each other is valuable and should be encouraged”. Yesterday afternoon, the Portuguese Chargé d’Affaires, Dr Mello de Gouveia, and the Brazilian Ambassador, Mrs Margarida Guedes Nogueira, previewed the exhibition with the National Librarian, Mr H. L. White, and a Portuguese scholar [Jack Braga].

Additional resources:

- ‘Remembering Jack Braga’, Review of Culture, no. 5, April/May/June 1988, Instituto Cultural de Macao, pp. 98-103.

- José Maria Braga, O Homem e sua Obra, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1993.

- Entry on J.M. Braga in his ‘A-Z’, National Library of Australia, MS 4300, series 7.2

- Pauline Haldane, ‘The Portuguese in Asia and the Far East: the Braga Collection in the National Library of Australia’ http://www.nla.gov.au/asian/pub/bragappr.html#app4

![Gordon Freeth, Minister for External Affairs [left], met Jack Braga at the opening of an exhibition at the National Library of Australia, 17 March 1969.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2023-06/image027.jpg?itok=reI9-egg)