Anthony Manuel Braga, Private Secretary, Music Lover

Anthony (Tony) Braga was the ninth of thirteen children of José Pedro Braga and his wife Olive Pauline (née Pollard). Like all his brothers, he was educated at St Joseph’s College, Hong Kong’s leading Catholic secondary school. He was close in age and interests to his brothers Noel, (b. 1903), Hugh (b. 1905), James (b. 1906) and Paul (b. 1908). These five formed something of a family within the family, and throughout boyhood and youth were inseparable companions, building life-long values of hard work, loyalty to each other and commitment to the causes in which they believed. When the Boy Scout movement came to Hong Kong, several of them joined it, following the lead of their elder brothers Jack, Delfino (Chappie) and Clement. Tony considered it a great honour to be a member of the 1st Hong Kong (St Joseph’s College) Troop of which his brother Hugh was Scoutmaster. He threw himself enthusiastically into the movement, gaining as many badges as he could, and soon became Patrol Leader. The family was not well off, and the Braga boys were often hungry throughout their boyhood years. The experience left Tony with a sympathy for the under-dog that never left him.

Left to right – Hugh, Noel, Tony, James and John on Robinson Road, close to home

Tony sustained a serious accident at the age of seven when he fell over a bannister in the family home. Hong Kong doctors proposed to amputate his right hand, but he was taken to Macau, where medical services were more advanced as so many British doctors were away at the war, and Portuguese army doctors saved the hand. He was in hospital for a year but was left with a permanent disability. The long period of absence from school created in him a love of literature, and enhanced the love of music that his mother had inculcated in all her children, though he was now unable to play an instrument. Later, he heard the famous guitarist Andrés Segovia play at the first City Hall on Queen’s Rd, Central. Decades afterwards, he recalled the experience: ‘Never before had I heard a classical guitarist, and I was under his spell. Then a tram came clanging by and spoiled it all. I resolved then that one day we would have a proper concert hall in Hong Kong.’

The 1920s were a troubled time in Hong Kong. There had been serious and protracted strikes in 1920 and 1922 when most of the Chinese workforce departed. Much worse followed an unruly demonstration in Canton on 23 June 1925 which called for another general strike against British imperialism. It was fired upon by European police from the British concession, Shameen, and there was serious loss of life, with 52 people killed and 117 wounded. This at once precipitated the called-for general strike and boycott of all European businesses and households. The servants in the Braga household and J.P. Braga’s office staff at once departed. [1] Later, J.P. Braga recalled ‘that was a disastrous year for the Portuguese of Hong Kong. Many savings of a lifetime vanished into thin air on that fateful afternoon in mid-June’. [2]

His business collapsed as well as his investments. Tony was about to sit for the Matriculation Examination for Hong Kong University, but tertiary studies were no longer a prospect and there was no employment in the commercial sector for some years. Instead, he became his father’s private secretary for more than a decade, though he later wrote of his toil during these years as ‘sheer drudgery’. [3] In August 1937, after more than a decade as his father’s private secretary he was appointed Property Superintendent of the Hongkong Engineering and Construction Company. [4] He gained this through the advocacy of his brother Hugh, General Works Manager, who was described by his father as ‘a key employee of the Company who had played the game by the Company’. [5] Tony retained his position until the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941.

In working for his father and for the Construction Co., Tony became well acquainted with the business dealings of Sir Elly Kadoorie and Sir Robert Ho Tung, who over many years were his father’s principal business partners. J.P. Braga’s leading interest in the inter-war years was in the Construction Co, of which he was Chairman and Managing Director. Tony’s business acumen and knowledge of his father’s affairs later led to his being nominated by all members of the family as sole executor for the winding up of J.P. Braga’s estate after the war.

J.P. Braga was perhaps more interested in politics than in business, and throughout a long public life had been a passionate campaigner for justice, whether it be the political rights of Filipino nationalists in the 1890s or the concerns of pig breeders in the New Territories of Hong Kong in the 1920s. He was an indefatigable campaigner for the rights of the little man. He became a member of the Sanitary Board in 1926 and was the first member of the Portuguese community to be appointed to the Hong Kong Legislative Council in 1929, serving two terms of four years.

Tony was his father’s loyal supporter throughout this time. However, he fully shared the elder Braga’s criticism of what a later generation of critics was to term ‘the unacceptable face of capitalism’. [6] Tony also acquired a distaste for what he saw as the ruthless commercialism of the business tycoons with whom he dealt daily. He developed a fascination for the Soviet regime in Russia, seeing in communism an effective riposte to the exploitation of the working classes that he saw all around him. Ideologically, this drew him away from the evangelical Christianity of his mother’s upbringing, but not from a reverence for her fine qualities. He would often refer to a song which she had taught her children: ‘Count your blessings’. [7] He was an excellent letter writer, and maintained contact with family members in various parts of the world as the originally tight-knit group began to spread to other parts of the world: James to the U.S.A., and after the war, Clement to Canada, Noel and John to Britain, Hugh and Maude to Australia, and Paul to the U.S.A. Wherever they were, Tony was unfailingly loyal, kind and generous towards the family.

As war clouds loomed in the later 1930s, Tony joined the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, becoming a stretcher-bearer. When war broke out on 8 December 1941, he was called up for active duty, but was on leave in Kowloon when the Japanese Army broke through British defences three days later. Prudently, he disposed of his uniform, and melted into the civilian population. However, some months afterwards, he decided to remain behind with his sister Jean to take care of the family home when his parents and other family members, Noel, John, Paul, Caroline and Mary were able to leave Hong Kong for the greater safety of Macau, the only part of the Far East not directly occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army. It was a courageous commitment: there was no means of livelihood, and he risked execution should the Japanese discover his membership of the Hong Kong Volunteers. Later, in June 1944, he joined other members of the family in the nearby Portuguese colony.

This period of comparative inactivity until the war ended in August 1945 gave Tony an opportunity to develop two long-term interests: a fondness for teaching and his love of music. While his sister Caroline taught the piano, Tony taught English. Many in Macau had no doubt about the eventual outcome of the war, and were keen to learn the language of what would certainly be the dominant culture of the post-war world. Tony was concerned that the younger children of his eldest brother Jack, also in Macau, spoke Cantonese and Portuguese, but little English, and gave them lessons too, knowing that, as his niece Maria, put it, ‘The ability to speak fluent English was essential if we were to make anything of ourselves in the outside world’.

Of the privations of wartime Macau, Maria wrote, ‘In those awful times necessities such as food, clothes and warm blankets became luxuries and money was in short supply for everyone. It was Uncle Tony who was generosity itself at that time and who did his utmost to help supply our every need ... He was just as kind and generous to his servant and to the poor and disadvantaged.’ [8] While opportunities for listening to or performing music were rare, it was still possible to read voraciously about classical music, especially the lives of the great composers. Tony was especially drawn to Mozart, at first lionised by the aristocratic world of eighteenth century Austria, and then allowed to die, unappreciated and forgotten. In Mozart’s life and music, Tony Braga’s twin concerns came together: compassion for the victim of oppression and love of beautiful music.

At the end of the war, Tony returned to Hong Kong with other members of his family, living for a period with his brother Hugh and his family on Boundary St, Kowloon, and later with his mother and sisters Caroline and Mary on Chatham Rd, not far from the Star Ferry. After their mother’s death in 1952, the three remaining unmarried members of the family eventually went their own ways, Tony joining forces with his brother Paul in the construction of a small apartment building on Bisney Rd, Pokfulam. He lived there for the rest of his life, surrounded by a growing collection of books and gramophone records.

Both Sir Elly Kadoorie and J.P. Braga had died during World War II. Recognising Tony Braga’s outstanding ability as a private secretary, his sons Lawrence (later Lord Kadoorie) and Horace engaged his services in this capacity for the remainder of his working life. Tony was able to hold in constructive tension his distaste for the methods of one of East Asia’s most significant capitalist families and his loyalty to his father’s business partners. For their part, the Kadoories valued his qualities, and in their employment, Tony became financially secure and was a successful investor.

Because of his business ability, all his siblings agreed in 1946 to make Tony sole executor of the estate of his father, who had died intestate. Unfortunately, he delayed winding up the estate for many years, planning to increase its value to the beneficiaries. There can be no doubt that he meant it for the best, but his procrastination led, after his death, to groundless accusations of malfeasance by a few family members.

He was keen to foster in the cultural wilderness of post-war Hong Kong an appreciation of the music and literature of which he had grown so fond, and was one of the prime movers in the establishment of the Sino-British Club in 1946. The intention was to establish a literary circle and an amateur orchestra. He felt that there must be in the colony many lovers of music and literature, like himself, both in the British and Chinese sections of the community. A true Internationalist, Tony sought to implement in the cultural milieu of Hong Kong the high-minded principles of the United Nations in these early post-war years before the hardening influences of the Cold War overwhelmed them. He elicited the support of the talented Dr Solomon Bard, whom he had known in musical circles before the war, when Bard returned to Hong Kong in 1947.

Tony served for ten years as Secretary of the Sino-British Club, and his foundational work was justly recognised in 1984 at the 10th anniversary of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Society, the successor of this early post-war attempt at an organised approach to music in Hong Kong [9]. He was bitterly disappointed when things did not work out as he had hoped. The literary circle which he intended should go hand-in-hand with the development of fine music never eventuated, and the orchestra developed as more of a cultural elite than he felt it should. He argued strongly against the change of name from Sino-British Orchestra to Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, and refused to continue as Secretary, believing that the original vision had been lost. He never regained a significant role in musical circles in Hong Kong, though he was associated with the movement to build a new City Hall in 1964. [10]

He also pioneered cultural links with the Peoples’ Republic of China during the 1950s and 1960s, at a time when inter-change between Hong Kong and its large and powerful neighbour was minimal. In this, his ideological sympathies were of assistance in China, though these initiatives did not commend him to the musical fraternity in Hong Kong. Dr Bard, in a phone call to this writer in June 2012, told of the pressure placed on several would-be members of the delegation who withdrew upon being threatened with losing their jobs if they went on a planned visit to China.

Tony retired from Sir Elly Kadoorie & Sons in 1973, and the remainder of his life was dominated by his love of music. He continued to develop his large collection of gramophone records and books. Every day began with Mozart, ‘than whom there is no better companion’, as he put it. He spent many hours preparing lectures on the life and work of leading classical composers. These were delivered to a group of friends and pupils of his sister Caroline. They began with Mozart, and included, over a period of some ten years, Chopin, Beethoven, Haydn, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann. His lectures were marked by a warmth and sensitivity to each composer’s development as human being and musician, and by a great empathy with him. The text was accompanied by a selection of recorded music illustrating the best elements of the composer’s style and skill. These lectures revealed much of Tony Braga’s essential humanity, his humour, and his considerable skill as a teacher. In addition, he prepared a scholarly series of lectures on the History of Keyboard Music since the Twelfth Century, delivered at the University of Hong Kong. [11] This ranged beyond Tony’s usual range of interests, which began with Bach and ended with Brahms. He had no interest in any twentieth century music, and no interest in music outside the mainstream of the Western European classical tradition.

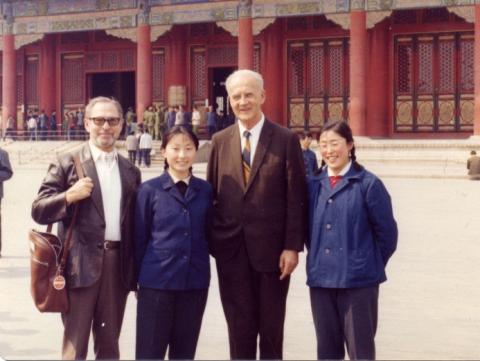

Left to right: Vandra Braga, Joe Braga (son of Paul), Stuart Braga, Tony Braga, unknown lady.

During his twenty-one years of retirement, Tony travelled extensively, visiting relatives in Australia, Britain, Canada and the U.S.A. on many occasions. Tony had a fund of jokes that he was fond of telling and re-telling, and would laugh until the tears rolled down his cheeks. His reputation for kindness and generosity continued undiminished, and he was always hospitable to those family members who visited Hong Kong from time to time. When his nephew Maurice lost his wife Meg to breast cancer in 1990, Tony paid for a round the world air trip to enable Maurice to get away for a much needed break, seeing family members in many places.

He was passionately loyal to his family, and was responsible for a major article by Beverley Howells on the Braga family that appeared in the South China Sunday Post in May 1987. More than the rest of his brothers, he was appreciative of the major contribution that his brother Jack had made to the history of Macau and Hong Kong.

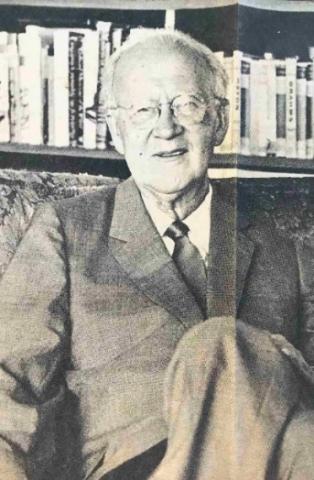

On his death in 1994, his extensive library passed to his sister Caroline, who arranged for the books to be sent to Australia, where they were presented to Trinity Grammar School, Sydney, where his nephew Stuart was Deputy Headmaster. Tony had visited the school in 1986, and had been impressed by the high standard of the school’s music, and by the opportunities that these boys had for learning music – opportunities that he himself would dearly have loved to have. In the intervening years, the school’s music had been developed vigorously, so that when a large new building was opened in October 1996, the A.M. Braga Music Library was one of its features. The inscription beneath a photograph of Tony Braga in the Library aptly summarises what he sought to achieve:

‘A lover of music. Always keen to share that love with others.’

References:

- Noel Braga Diary, 23 June 1925.

- J.P. Braga, Portuguese pioneering: a hundred years of Hong Kong, 1941, p. 12.

- In a note written for the golden wedding anniversary of his brother Hugh and sister-in-law Nora, August 1985.

- Minutes, Hongkong Engineering and Construction Co., 26 August 1937. By then, his father’s term of office as a member of the Legislative Council had concluded and his affairs were much quieter.

- J.P. Braga to Sir Elly Kadoorie, 13 June 1938. Hong Kong Heritage Project, A02-15.

- Edward Heath, British Prime Minister, quoted in The Times. 15 May 1973.

- Johnson Oatman, Jr., 1897.

‘Count your many blessings

Name them one by one

And it will surprise you

What the Lord has done.’ - ‘Eulogy to Anthony Manuel Braga, May 1994’.

- Cynthia Hydes, “A.M. Braga and the Sino- British Orchestra” in Celebration, a publication issued by the Hong Kong Philharmonic Society Ltd, December 1984.

- Interview with Dr Bard, Sydney, December 1995.

- The manuscripts of all these lectures are now in the Stuart Braga Papers, State Library of New South Wales, series 24.8, folder 6

Additional resources:

- Celebration - A commemorative booklet marking the 10th anniversary of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. Hong Kong, December 1984.

- Article by Cynthia Hydes, ‘Anthony Braga and the Sino-British Orchestra’, pages 14-17.

- ‘Eulogy to Anthony Manuel Braga, May 1994’, by Maria [Mariazinha] Braga.

- Hong Kong Standard, 7 September 1994. Article by Vernon Ram.

- Information from Dr Solomon Bard, Sydney, December 1995 and June 2012.

Authored by Stuart Braga, nephew. 20 October 1996, revised 25 October 1996, 25 March 2001, 21 August 2007, 11 May 2009, 25, 29 October 2020.