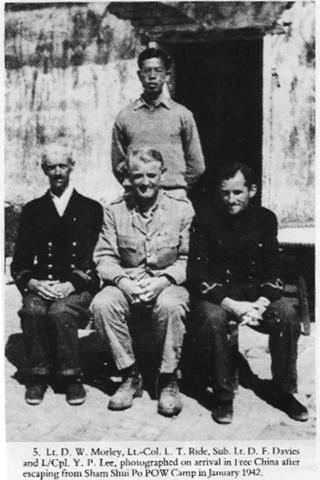

78 years ago, four escapees from the Sham Shui Po Prisoner-Of-War camp were cautiously making their way north through the New Territories, hoping to get through Japanese lines to reach Free China. The group was led by Lieut-Colonel L. T. RIDE, and this is his report of the escape.

4. REPORT ON ESCAPE FROM P.O.W. CAMP, SHAMSHUIPO, HONGKONG by L. T. RIDE (Late Lieut-Colonel H.K.V.D.C.)

1. ESCAPE PARTY PERSONNEL.

- L. T. RIDE, Lieut-Colonel, C.O. H.K. Field Ambulance

- D. W. MORLEY, Lieut (E), H.K.R.N.V.R.

- D. F. DAVIES, Sub-Lieut, H.K.R.N.V.R.

- Y. P. LEE, L/Cpl., H.K.V.D.C. Field Ambulance

2. PRELIMINARIES.

No advantage of escaping was taken of the chaos which existed immediately after the surrender, for it was hoped that in my capacity as OC Field Ambulance I would obtain permission from the Japanese to search the hills for the wounded which we knew must still be lying there in numbers.

On the 28th December after three days of futile endeavour, I was given the final official reply: “The Imperial Japanese army will look after all British wounded”, and it became obvious that permission for this work would never be given to us; preparations for the escape were therefore immediately embarked upon; the main difficulty encountered was complete lack of information concerning what areas were occupied by the enemy, and how closely these areas were guarded.

A scheme for slipping away by junk with a merchant marine officer to either French Indo-China or British North Borneo was fortunately nipped in the bud by the segregation of all military personnel, preparatory to transfer to Sham Shui Po. On the afternoon of 29th Dec 1941, all military personnel were warned to parade early on the morning of 30th December bringing with them food, blankets and clothing, the quantity of these being limited only by the amount that each prisoner could carry.

Fearing a Japanese search of our kit, I discarded all my 1/20,000 maps of the New Territories, but secreted amongst my personal effects a 1/80,000 map which covered the whole of the New Territories and the shores of Mirs Bay. Although I was not in possession of a small compass, I did not risk taking a prismatic compass as I feared its detection would reveal my intentions, whereas the presence of the map could be explained by the fact that it was mixed up with certain Field Ambulance records (nominal rolls) which I was carrying as cover. I collected as much bully beef, sardines, biscuits, Bovril and certain medical supplies as I could carry, but most of these had unfortunately to be consumed or used in the camp as the Japanese did not provide us with food for the first few days.

3. SHAM SHUI PO

Our destination on the 30th Dec was not communicated to us, but the most persistent rumours were that it was either Formosa or Japan. It was not until we were aimlessly led around the Kowloon streets by Japanese guards that it became obvious we were to be imprisoned (temporarily at any rate) in Kowloon. In view of the inadequacy of the camp guards in these early days and the fear that Sham Shui Po was only a temporary stopping place en route to Japan, an early escape was indicated; any fear that such plans would be frowned on by our own senior officers was dispelled on the 31st Dec 1941 when Brigadier Peffers reminded heads of services and commanding officers that it was the duty of all POW to escape. I immediately informed General Maltby of my intentions, but as I was Senior Medical Officer in the Camp he asked me first of all to try and organise the medical services and alleviate the terrible conditions in the camp with the meagre facilities at our disposal.

I agreed, but it was obvious from the start that we were not going to get any help from the Japanese and I therefore informed the General that I would stay only as long as I felt I was able to be of use. With no medical supplies at all forthcoming from the Japanese, all we could do was to arrange for M.Os to be posted to units, to allocate buildings for M.I. Room, hospitals and isolation hospitals for both British and Indian troops, and to institute sanitary fatigues and camp inspections.

Our “hospitals” consisted of wrecked buildings from which all windows, doors, fittings, lights, taps, baths, chairs, beds, furniture and wooden floors had been removed. Sanitation facilities did not exist; there were no latrines nor did we have any implements or tools to dig them. The only medical equipment, supplies or medicines we had were those which members of the Field Ambulance were able to carry into the camp in their pockets.

Within the first few days we already had about a dozen European cases of dysentery on our hands and the daily sick parade in a camp of 6000 was considerable and soon exhausted our meagre supplies of pills and powders; on the 6th January 1942 the Japanese brought into the camp 120 Indians suffering from dysentery (many of them too weak to stand) and 12 British; we had no medicines, no beds, no blankets, no disinfectants, no bed pans and no nursing orderlies who could speak Urdu.

On the 5th January I managed to obtain permission to visit Argyle Street camp where I found similar conditions prevailing; they had 69 Indian and 13 British suffering from dysentery, and 43 British and 12 Indians in “hospital” for wounds and malaria, three of these were suffering from secondary haemorrhage and the surgeons were powerless to do anything – they simply had to stand by and watch their friends die. They had already had 6 deaths and we had had 3, and these had to be buried in graves dug in the camps. The Japanese were not interested.

We made daily representations to the visiting Japanese medical officers for help but all to no purpose. With dysentery already rampant and uncontrolled in the camp, and cholera endemic in Kowloon, I was convinced that the hot weather would see epidemics of these diseases sweeping through the camps with disastrous mortality; I had worked during the two recent cholera epidemics in Hong Kong in which the high mortality amongst the undernourished Chinese was a marked feature; our undernourished prisoners would fare no better and in my opinion the end of the summer would see 60% of our people casualties. I therefore saw General Maltby again and told him that in my opinion the only way to save the lives of most of the prisoners was for someone to escape and try either to arrange for the smuggling of medical supplies (especially vitamin preparations) into the camp, or by broadcasting to the world the appalling conditions in the camp, to force the Japanese to treat the prisoners better. To be of any use some one had to go at once and I proposed to get a party together and leave almost immediately. (In recording this I do not wish to give the impression that this was the prime motive for my escape; the prime motive as with all escapers was the desire to be free; I estimated that the chances of being killed while attempting to escape were less than the chances of death if one remained, which latter as stated above I estimated as 6 to 4 on. Others thought differently; one brother officer to whom I put the proposition placed the chances of a successful escape at 10 to 1 against). I promised to inform the General when I was going.

4. PLANS.

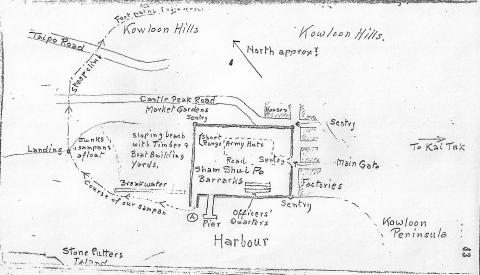

The basic plan was to recruit a party of 4 or 5 - including one Cantonese - to gain the range of hills to the north of the camp and east of the Tai Po Road and then make for Nam She (M.R.408712, H.K. and New Territories 1/20,000) and there either hire or steal a junk and cross Mirs Bay and make for the Waichow area where rumour had it that there were Chinese troops.

I revealed to L/Cpl Lee (a Chinese lad who had been closely associated with me in both civil and military work for some years) my plans and he agreed to come with me. He was in No. 3 Coy (the H.K.V.D.C. company) of the H.K. Field Ambulance and was housed with the Volunteers in another part of the camp. I had him transferred to my quarters on the pretext that I wanted him to help with the records dealing with No. 3 Company, and we were thus able to discuss our plans without arousing undue suspicion.

We immediately set about collecting information about sentry posts, their beats, their times of relief, times of moon rise, phase of moon, high water etc. Each day we met and studied and memorised (with the aid of the map) the hills which could be seen from the camp.

It was soon evident that there were three ways out of the camp;

- (a) through the fence on the North East boundary of the camp;

- (b) through the fence on the sea-wall at the North West boundary of the camp;

- (c) along the break-water which extended from the westerly corner of the camp (M.R. 186594) to a point 182587.

Plan (a). This method was relatively easy for Chinese because the fence was composed of only a few strands of wire and for the first few days this was down for a stretch of about 20 yards; it was inadequately guarded and all day large crowds of Chinese food sellers collected on the other side of the fence selling food to the prisoners. Many Chinese prisoners escaped through this fence and quickly mingled with the crowds outside during the first few days. For a European this method was impossible but at night one could get through easily; but once outside one would have to do a belly-crawl of about 100 yards through vegetable gardens which provided very little cover and which were patrolled by Wong Ching Wei Chinese Police.

Plan (a) was abandoned as a means of escape for a party, but remained a possibility for L/Cpl. Lee.

Plan (b). The sea-wall was about 8-10 feet high and on it was a wire fence supported on concrete posts about 10 feet high. At certain places it was possible to get through the fence when the sentries were facing another direction or through the typhoon drains which emptied through the wall into the sea. At low water one would land on mud and nearby were lying a large number of logs awaiting use by the neighbouring junk-building yards, which would provide immediate cover and protection. This method provided a relatively easy get away, but one would have to get through the ship building yards and close observation showed that the Wong Ching Wei men frequented these yards both day and night.

Plan (b) was abandoned as too risky until we had more information about these ship-building yards.

Plan (c). At the western corner of the camp was a small slipway and also a short wooden pier. These were out of bounds but the pier was used during the day for tipping rubbish into the harbour, and at night it was used as an open air latrine.

In the evening, the path along the harbour wall on the south west of the camp from Jubilee Buildings to the Pier was a favourite promenade for prisoners, but after 2030 hours it began to get cool and most people returned to their quarters. For a few nights I took up my post in this open-air latrine at about 2100 hrs and stayed there till mid-night watching movements of sentries and junks and from my observations decided this was the spot to make one’s “get-away”.

Sentries. Sentries were placed at the main gate of the camp (190593) and along the South-East and North-East boundaries; sentry posts were also located at the southern and northern corners of the camp and these sentries had a clear view of the south west boundary (the harbour wall) and the north west boundary (the typhoon anchorage wall); other sentries made occasional and irregular visits to the slipway and pier at the western corner of the camp. The sentry at the southern corner of the camp frequently fired at any junk or sampan approaching too close to the camp.

Outside the camp fence could be seen numbers of armed Japanese (probably gendarmes) and Wong Ching Wei Chinese (distinguished by a white arm band and a stick); their main duty seemed to be to illtreat the Chinese who collected in large numbers near the camp, and from the scenes one witnessed daily it was also certain they would also deal most effectively with any escapees.

After a few days the Japanese began to forbid trading through the fence at the northern end of the camp and it was obvious that the traders would soon try the pier, selling their wares from sampans. This would be immediately followed by the posting of an extra sentry at the pier with consequent blocking of this escape route. (This later was actually what happened).

I therefore decided to adopt Plan (c) and put it into operation as soon as possible. In order to put as great a distance between ourselves and the camp on the first night it would be necessary to escape soon after night fall; for the escape we would require darkness; for our flight through the difficult hills, moonlight would be essential for quick movement; the best time to leave the camp was about 2100 hours and we needed to choose a night when the moon rose between 2200 and 2300 hrs by which time we should be in the hills if all went well. On Jan 4th, 1942, the moon rose about 2015 hours which meant that we should have to make our attempt within the next few days.

The general plan decided upon was that Lee should slip out of the camp through the north east fence and bribe a sampan to come to the vicinity of the pier the next night and, at a pre-arranged signal, come in to the slipway and take the party off. The initial phase of this plan was almost immediately foiled by the repairing of the fence along the north east boundary, the prohibition of Chinese from approaching any where near the fence and the posting of additional Japanese sentries inside, and more Wong Ching Wei Chinese outside the fence. This meant Lee had to get out from the pier also.

We now considered the possibility of walking along the break-water which was not submerged at low tide and swimming from the further end to the shore. This meant the inclusion in the team of at least one strong swimmer and it was during my search for a L/Bdr whom I knew to be a good swimmer that I met Lieuts Davies and Morley. I had, during the last few days, tried unsuccessfully to persuade a number of my friends to join my party but they had all, for various reasons, turned the offer down with thanks.

Having known both Morley and Davies for years I put to them the case in favour of escaping as I saw it and they were persuaded to join. Observations on the times of low water showed these did not fit with possible dates as indicated by the time of moon rise, hence we were thrown back onto the sampan plan.

Action was precipitated on 8th Jan by the orders of the Japanese that all Chinese in the camp were to parade immediately, bringing all their belongings. Rumour had it that they were all to be liberated; this I did not believe, but Lee felt we should not miss even this remote chance of getting him out of the camp so I agreed to his going along.

He was back within an hour stating that they had been segregated behind barbed wire in another part of the camp and were not being liberated at all. In the disorder which prevailed whenever the Japanese tried to organise things in the camp, Lee had slipped out again and reported back to me. I hid him in the room we were using as M.I.Room and smuggled his kit out of the segregation area.

The die was now cast; if Lee (being a Chinese) were found in my room there would be trouble, so he had to go that night. I had noticed that at high tide, sampans were able to pass between the slipway and the break-water; during daylight they were frightened to come so close to the camp for fear that the Japanese would fire on them, but towards dusk an occasional one took advantage of this short cut into the shelter behind the breakwater; the scheme was for Lee to take up a position at the bottom of the slipway and if a sampan came through, either to get on it at once or to bribe the owner to return for him about 9 p.m.

Luck was with us; on the afternoon of the 8th January Lee took up his position (with a scarf wound around his head so that it was difficult to recognise him as a Chinese) a short time before high tide and one, and only one, sampan took the short cut. The owner refused to stop but Lee hailed him and told him to return immediately after dark.

Late that afternoon we secreted Lee’s kit near the slipway and joined the promenading crowd near the pier. To our dismay the sampan turned up while it was still very light; it lay off the pier about 200 yards distant in a most conspicuous and unusual position and attracted a lot of attention. Many prisoners thought it contained a Japanese sentry, a story which we encouraged in order to stop people from congregating and watching it. By 1945 hrs it was dark and all prisoners had gone back to their quarters except one senior Naval Officer who seemed inordinately interested in the sampan. In the end I asked him to move off as we were expecting a message from outside. As soon as he went and the coast was clear of sentries, we signalled the sampan and put Lee aboard. It later transpired that the reason the sampan returned was because its owner thought Lee was a Japanese sentry! Had he known he was a Chinese trying to escape he would not have dared to return!

5. FINAL PLANS.

The final plans were as follows; Lee was to procure old coolie clothes for himself and if possible also for us; he was to buy some tinned food; he was to reconnoitre the Castle Peak Road and note where the sentries were posted; he was to bring the sampan back on the evening of the 9th at 2100 hrs and lie alongside the breakwater about 200 yards off the pier until he received my signal (I was to light a cigarette and uncover the flame of the match three times with my hands); we were to secrete our baggage in a small concrete unused shelter about 30 yards from the pier just after dusk; when the coast was clear, the sampan was to be signalled and we were to move into the slipway with our kit and hide under cover of the wall. The sampan was to take us along outside the breakwater and land us at a point determined during the day by Lee; we were to cross the Castle Peak Road separately at intervals, and then move together due north crossing the Taipo Road at about 184608, and passing around the south side of Piper’s Hill and Eagles Nest, gain the north side of the hills through the pass at 195614; from here we were to make for the path along the catchment which runs from 189619 to 224633; walking along this catchment would be easy going and we expected to be at the eastern end well before day light; we were then to strike across the difficult country along a line Sugar Loaf Peak (235633), Stokers Peak (252639), Buffalo Hill (268642), Pyramid Hill (287667), then through the narrow neck of land north of Tai Wan (312666), thence to Nam She (408712); all passes were to be reconnoitred before the party approached them lest they were guarded by Japanese; speed commensurate with silence was to be the key note of the first night in order to get as far from the camp as possible before daybreak; we were to follow the usual procedure of travelling by night and lying up by day while in the danger zone.

On the 9th Jan we received orders that nominal rolls of all units had to be prepared and handed in that day; this meant the institution of roll calls in the camp; Lt. Morley approached his C.O. and informed him of our plans and asked that his and Davies’ names should be left off their nominal roll; I instructed my Sgt. Major to leave my name off the Medical Detachment roll and not to send the roll in till the morning of 10th Jan; this would mean that the only way the Japanese could discover our escape was by noticing my own personal absence; this was quite a possibility because their medical officers on their visits always sent for me immediately they entered the camp or else came directly to my room. (What actually happened was that the Japanese M.O. – Lieut. Sawamoto – who came most frequently was transferred to Canton on Jan 9th, hence his successor did not know me at all.)

6. FINAL PREPARATIONS.

During the morning inspection of the so called “isolation hospital” by the General and Brigadier Peffers on Friday 9th Jan, a group of Japanese officers arrived with the information that the Japanese General was to visit the camp that afternoon; throughout the day the Japanese were in a complete flap. We accompanied these visiting officers to the gate when they were leaving and there we found Col. Simson, A.D.M.S. who had been given permission to come over from Bowen Road Military Hospital and visit the camp. He was not allowed in, but was permitted to speak to us through the gate. While we were there, the Japanese camp Commandant brought in a Middlesex private, who, he said, had tried to escape. Through an interpreter he said to the General that this time he was going to be lenient, but in future any one caught escaping would be shot. The General was told to communicate this to all the prisoners; as we were walking away from the gate General Maltby instructed Brigadier Peffers to pass this information on, adding “This does not mean they are not to escape, but it does mean they are to make very certain of their plans”. I then informed the General that I was going that evening and promised to come and see him before I went, in order to collect any messages or reports he might wish me to take through. The day was spent in making final preparations.

Food. I had purposely (but selfishly) withheld certain tins from the communal food pool but unfortunately the amount withheld was not very much. Davies and Morley bartered their remaining tobacco and cigarettes for some food.

- Morley carried 2 tins of Tuna fish (7 ozs each), 1 large tin of sardines and a small piece of chocolate.

- Davies had 3 tins of Tuna fish, 1 lb tin of corned beef, a small bottle of sugar, and 1 tin of pork and beans.

- Lee had 2 tins of Chinese curried meat and chicken.

- I carried 18 hard army biscuits, a tin of bully beef, a packet of raisins and 30 soft biscuits.

This food was merely to last us while we were in what we thought would be the occupied part of the New Territories and after that we planned to live on the country.

Money. I regret I have no record of the amount of money we had. I think I had about $300 H.K. of which about $200 belonged to my Field Ambulance Imprest account and for which I had permission from the General to use in the escape. Morley also had a few hundred dollars and Davies and Lee practically nothing.

Clothing and Equipment. Lee was to wear coolie clothes because his main job was to be contact man and to procure help, food and information from Chinese en route; the clothes he eventually turned up in were a glorious sight, complete with holes and patches.

At the last moment I decided against us wearing Chinese clothes, because Chinese carrying their belongings in any other manner than on a bamboo pole would have been just too ludicrous, and would have attracted more attention than ever.

Lee carried his kit in a sack which he later converted into a pack.

Morley was wearing old blue overalls over his navy uniform, and carried a light naval raincoat, haversack, field glasses and water bottle; he was unable to procure rubber shoes and wore hosetops over his boots to lessen the sound.

Davies wore a naval jacket, khaki battle dress trousers and rubber shoes, and carried a haversack, his boots and about 15 feet of rope.

I only had khaki drill uniform so I wore a pair of shorts and my pyjamas over my thin underclothing. I carried a pack, waterbottle, raincoat, haversack and boots, wearing rubber shoes.

7. THE ESCAPE

((Readers may wish to have the maps of L T Ride's escape route open so that they can see the locations described.))

During the late afternoon of Jan 9th I saw a large mounted detachment of Japanese moving up the Tai Po Road. I estimated they would bivouac at the western end of the catchment for the night; questioning a prisoner who had been brought in from the New Territories a few days before, I learned that the Japanese had used the catchment as a shelter for their horses; I therefore made a last minute change of plans and decided not to go anywhere near the catchment but to remain up as close to the crest of the ridge as possible. At 1800 hrs we hid our packs etc as arranged and I went to see the General but he was engaged. I returned to my quarters and informed the officers under my command that I proposed to leave that night; only two of these officers had any previous knowledge of my plans; they were my 2nd i/c Major J.N.B. Crawford, R.C.A.M.C. and Capt. Coombes, R.A.M.C. I left with them instructions as to what to say to the Japanese (if they asked for me personally) in order to delay their discovery of my escape.

At 2030 hours Lieut Morley came to say that a sampan was already lying off the pier; I recognised it as ours; it had again come too soon and was attracting dangerous attention of a group of prisoners who had congregated near the pier. As on the previous night I had to ask them to disperse which they obligingly did; we then went back for our kit but I now had no time to visit the General. We made a quick reconnaissance to see that no sentries were approaching, gave the signal and the boat came in.

By this time it was quite dark, but as the sampan approached another group of sailors arrived on the scene and had to be persuaded to move on. When the sampan came in to the slipway, the coast was clear and we hastily climbed aboard with our kit; the added weight grounded the sampan and we made far too much noise refloating it. Once afloat again we moved off, the boatman ferrying us along outside and close to the breakwater. The night was very dark, the sky was clear and the phosphorescence alarmingly bright, and there is no doubt that a sentry placed any where near this corner of the camp would have made this method of escape impossible. When we were about half way along the breakwater, we heard lights-out blow – the camp time 2100 hrs, 2110 hrs by my watch. On turning north around the end of the breakwater we hid in the bottom of the sampan for we had to pass close to a number of junks lying at anchor in the shelter; we were hailed by a few of these junks but were not stopped, and it is uncertain whether the junks had Wong Ching Wei police on board or not.

We landed at a point approximately 182602, paid the sampan owner $50, warned him to say nothing about us, and dismissed him. Here again the phosphorescence was alarmingly bright, every footfall on the sand seemed to light up the beach for yards around.

The crossing of Castle Peak Road was reconnoitred and an armed guard (whether Chinese or Japanese we could not tell) was seen standing near a light about 30 yards to the west of us. We made the crossing separately without being challenged and followed a path we had observed from the camp to be very frequently used by Chinese. Unfortunately this path led us too close to Piper’s Hill Service Reservoir (182606) which we assumed would be guarded; in the dark we found it impossible to negotiate the deep scour to the east of this point, hence we had to come right down to the Pipe Line again before we could strike east to cross the Tai Po Road at the chosen spot (184608). It was 2210 hrs before we arrived at the road and the going was much more difficult and slow in the dark than we had calculated.

I reconnoitred the road, found it all clear and we all crossed; the other side of the road was a cutting about 20 ft. high with a fairly large re-entrant at the point where we crossed; in this re-entrant at the foot of the cutting was a large shell hole. The road both above and below us passed through cuttings on both sides and it was too risky to pass along the road looking for an easier way out into the hills, for if we met any traffic we would be trapped. While searching for a way up the cutting a truck approached from the direction of Kowloon and we hid in the shell hole. The truck was climbing slowly and was fully loaded; a number of Japanese were sitting on the load at the back, and one of these was flashing a torch along our side of the road. We held our breaths, fearing the truck would stop, but to our intense relief we were apparently unseen for it continued on up the hill. To move along the road would be obviously fatal so with the aid of the rope the party immediately scaled the cutting face and gained the partially wooded hillside above, where we were safe from observation from the road.

We set off in the direction of Eagles Nest (188612) and it was most noticeable how helpful was the small amount of light from the Kowloon street lights even at that distance. There is no doubt that but for these lights we should have had to wait till moonrise. On the steep slopes to the south of Eagles Nest the rope had to be used again for the second time.

The street lights also served another purpose; I had noticed on the map that the pass at 195614 was almost in a direct line with the continued line of Nathan Road, so all we had to do was to keep going east till we were in line with the Nathan Road lights and then turn north. It was after 0100 hrs on 10th Jan that we had our last glimpse of Kowloon and the camp as we went through the pass. On the north side of the hill it was pitch dark and we had to find our way through thick undergrowth and long grass; the strain was beginning to tell on us and our progress very slow; I therefore decided on another change of plan; we had started off on the assumption that the passes in the hills would be guarded and that the paths would be used by sentry reliefs and therefore we must keep clear of all paths; when we found no guards at the pass, I considered it to be safe to use the high paths and this made our going much easier and quicker; it was however much noisier, for the rough going had long since torn Morley’s hose tops (which he was wearing over his boots) to shreds and his heavy boots on the stone track could be heard a long distance off. It was while he was walking on the edge of the narrow track to lessen the noise that he went over the side in the darkness, and to us listening up on the track it seemed as though he would never stop rolling. For the third time the rope proved invaluable and it took us about 10 minutes to rescue him without loss “save for his cap, one glove and his dignity”, as he said.

At about 0200 hrs the moon rose and from then on our pace was much better. Just before sunrise we came across one of the many concrete direction blocks which we had kindly put all through the New Territories to direct the enemy forces to our Pill Boxes, O.Ps and H.Qrs. This one showed we were near an O.P. named Moffat’s Look Out, but that did not help to fix our position because it was new since I had been in that area last. We found some old trenches near some rocks, had some breakfast of biscuits and chocolate and hastily prepared to spend the day there. At day break I crept out onto an exposed point and fixed our position as being on Sugar Loaf Peak (235633). The Tai Po Road was seen to be in full use despite our demolitions!

At 1000 hrs it came on to rain and prevented us from sleeping; visibility was poor so, although we were tired, stiff and footsore, I decided to take advantage of the bad weather and push on. Unfortunately the rain turned to fog and we got hopelessly lost. Early in the afternoon the fog suddenly lifted and we found ourselves near a military road; we must have been near Grasscutter’s Pass (242622) and had therefore been travelling south instead of north east! Before we knew what was happening we met a group of Chinese, so we hurriedly fled to the hills to regain the cover of the fog, lest they should reveal our presence to any Japanese who may be in the vicinity.

At 1700 hrs we stumbled on the entrance of P.Bs 203 A & B; we were wet through, bitterly cold, very stiff and sore, hungry and low spirited, not to mention lost; the entrance led into a tunnel about 30 yards long at the other end of which was the pill box filled with Rajput debris. It was at any rate dry and safe so we went into the pill box, built a fire using ammunition boxes for fuel, warmed and dried ourselves and had a meal of curried chicken and biscuits. The positions of all our pill boxes were marked on my 1/20,000 maps but I had left these in the camp and had unfortunately not marked them on the map I carried; I was the only member of our party who knew this area, but I could not remember exactly where P.B. 203 was situated.

Hearing grasscutters talking on the hills outside, Lee was sent out to find out exactly where we were; he came back with the news that we were near Kun Yam Shan (248631); I could not help feeling that anywhere west and south of Buffalo Hill (268642) one was liable to run into Japs, so I decided to push on even though we were still enveloped in fog. The fire and food had put new life into us, so on we went, cheerfully trying to reach Buffalo Hill.

Before long we were absolutely lost again and when darkness came on we found ourselves on a path which suddenly seemed to end in obscurity. There was no point in going back; we could not go forward, the hill was too steep for us to go either up or down in the darkness and fog, so we just had to lie down and wait for the moon. It poured with rain later and was bitterly cold, but still although we were getting a bit depressed, we were free!

11th January.

At 0300 hrs the moon rose and the fog lifted; we found we were on the edge of a deep nullah; we climbed across it and followed the path on the other side which led us up a steep hill and into the fog again. As we climbed, the fog got thicker; it was useless to climb further so we decided to await daylight; as we sat on the hillside the fog lifted from time to time, and during these periods we saw below us water and across it moving lights. What could this be? There was only one way to find out and that was to go down and see. This meant changing our basic plan which was to keep away from the lower levels; but Hong Kong fogs last sometimes a week or two weeks without lifting and we did not have food enough to remain in the hills for that length of time so at 0430 hrs we decided to descend. Just before day-break we arrived outside a village which turned out to be Siu Lik Yuen (245650); in the last 24 hours we had made no progress at all at the expense of much energy and some valuable food. Near the village was lying a recently-shot Chinese; this meant only one thing - Japanese. The villagers were already moving out into the fields so we hid while Lee approached them and found out the name of the village and also that the Japanese came in there each morning from the Tai Po Road on the other side of Tide Cove. We must push on immediately and in order to move more quickly we decided to follow the path north along the eastern shore of Tide Cove.

At 244668 we saw two sampans and decided to ask them to take us out into Tolo Harbour and if they would not take us across Mirs Bay perhaps they would land us on the north of Tolo Harbour which we felt would be clear of Japanese. Lee approached them but they refused saying the Japanese daily patrolled the harbour and came ashore on the eastern side every day raiding the villages.

Actually while Lee was reporting this to us we saw some one crossing Tide Cove in a rowing boat from the Riding School (232668); he was dressed in a white uniform and was a very bad oarsman. We immediately climbed up the hill for about 500 feet and hid in the shrubbery where we had a good view of him. He went straight to the sampans and all the Chinese fled ashore excepting one. The Japanese visited both sampans and must have been told about us because he came ashore, picked up his rifle and came along the path searching the hillside for us; for a solid half hour we lay there watching him looking for us but at last he gave up and went back to his boat and started to row back to the other side of the inlet; fortunately for us however the moment he got out of the lee of the land a strong north east wind struck him and blew him in the direction of the head of the Cove. He was such a bad oarsman (he had great difficulty in keeping his oars in the rowlocks) that it is doubtful whether he had any time to worry about us. Yet as he rowed he was facing us so we dared not move until we saw him land at about 233654 and make towards some houses nearby.

This lesson was enough for us; Tide Cove was too unhealthy; the sun was now well up and the fog had lifted from some of the surrounding hills; the summit of Turret Hill (258664) at our back was clear so I decided we should climb it, set our map and memorise details of the "promised land" to the east before we moved on again. It would be a stiff climb and our water bottles were nearly empty and the day promised to be very hot.

As soon as our Japanese friend was out of sight we started off and after about half an hour found ourselves in a secluded valley with a stream running through it. There we built a fire, boiled water in our dixie lids (most of the dysentery cases in the camps were due to drinking unboiled water in the New Territories), filled our water bottles, had some biscuits and then set off on our climb. It was after midday when we reached the top; we were all practically exhausted after our poor diet, lack of sleep and strenuous effort during the last 36 hours.

During this climb I twisted my right knee and this injury caused severe pain and gross discomfort during the next week or two. On the summit of Turret Hill we dried our sweat-drenched clothes, lunched on a tin of bully beef plus 3 biscuits each, identified our position and the surrounding hills, and memorised our route.

At 1445 hrs we set off on the steep descent; Mui Chi Lam (267661) village we found deserted by all but one old man because the villagers had seen us on the hill and thought we were Japanese soldiers; from him we learned that there had been no Japanese in that area for some days, nor were there any now in Sai Kung (305649); in view of our weak condition and the difficult and unknown country to the east, our shortage of food and my bad knee, we decided to make for Sai Kung and try and get a junk there as it is a big junk and sampan centre.

At Mau Ping (275653) the villagers were most friendly and gave us the first big meal we had had for a fortnight. Lee was sent on ahead to Sai Kung to try and arrange for a sampan while we followed later with a guide, arranging to meet Lee at a rendezvous outside Sai Kung after dark at 2000 hrs. We arrived at our rendezvous at 1940 hrs and hid by the side of the track and awaited Lee's arrival. It was a very dark night and again bitterly cold; our guide slipped off in the dark and deserted us, and when at 2200 hrs Lee had not returned we feared something had happened to him since Sai Kung had the reputation of being infested with pirates and brigands.

I then decided on what afterwards seemed a most futile move, and that was to go to the village and search for Lee.

We found a house with a light showing, and knocked at the door. A Chinese answered our knock, but as soon as he saw us he slammed and bolted the door and put out all lights; in the room beyond we could hear muffled voices in excited conversation and as we were unarmed we immediately decided that to search for Lee in the village was futile and that we had better return and wait at the rendezvous; we had hardly gone 20 yards when we met him; the trouble had been that our guide had taken us to the wrong rendezvous and Lee had been searching for us for 2 hours. His information was that the town was most unhealthy and that there had been fighting there that day between Wong Ching Wei people and the brigands; we had to flee to the hills immediately and this we did as fast as the darkness and my knee would allow us.

12th January.

We passed a dismal night huddled together on the hillside, being too cold to sleep; before daybreak we found a dense wood and made it our hiding place, for we knew the Wong Ching Wei people would be after us. We learned from Lee that there was only one man in Sai Kung who might be able to help us so at daybreak he went to try and find him and I gave him instructions that he was not to return during day-light unless the coast was absolutely clear; we moved further into the wood and hid in the dense undergrowth; a few minutes later the wisdom of this move was evident when we heard searchers in the woods. The searching went on for some hours and as we were lying in the fallen leaves, the slightest move on our part would have given us away when the searchers were very close. At about 1100 hrs the searchers apparently gave up and Lee returned about noon with the information that he had not yet met the man he wanted to see, but others had suggested that we might get a sampan at Sai Kang (300691); as this would have taken us back again to Tolo Harbour region, I would not agree and sent Lee back with orders to try again and to return after dark.

After taking the precaution of hiding our money in nearby trees so that if we were caught, Lee would be able to collect and use the money, we settled down to spend the long afternoon in hiding; from 1430 to 1700 the wood was again subjected to a persistent search; this time the searchers came within a few yards of us and at times called out "Hullo" but we dare not move or answer lest this should be a trap. At 1745 we were suddenly scared out of our wits by the approach of some one making straight for our hiding place, but it turned out to be Lee with good news. While we were awaiting night fall he told us the following story.

When the Japanese moved out of Sai Kung they left Wong Ching Wei Chinese in charge, but immediately robbers from neighbouring districts invaded the area and all was chaos, and security of life and property disappeared. About the 9th January a new group moved in - these were the so called "Red" guerillas from across Mirs Bay. They had driven the robbers back into the hills and had restored order. When we went into Sai Kung the previous evening the news spread through the town and it developed into a race to catch us, the Wong Ching Wei people to hand us back to the Japanese and the "Reds" to save us; the afternoon searchers in the woods turned out to have been the friendly "Reds", and the fact that we were able to hide from them so successfully put us up in their estimation tremendously.

About dusk we moved out of the wood to a rendezvous, and there I met Kong Sui and thus began the remarkable association between the Reds and the future B.A.A.G., an association that has had many amazing ups and downs, but one which I still feel has been greatly to our benefit.

We were first of all taken to a village named Pak Kong Au (296654), given a big meal and then after dark we moved to Sai Kung (305649) and were given shelter in a school. There we were given a hot bath each (the first for many weeks) and more food. About 2130 hrs the head guerilla came in and he questioned us thoroughly. When he was satisfied as to our bonafides we discussed future plans. We gave them the numbers and positions of the pill boxes that still had arms and ammunition in them which pleased them tremendously. We made plans for getting messages back into the camp to the General and I then and there wrote one to be sent off immediately. (We learned later that the lad who tried to get this message in was shot at and killed by the Japanese as he was approaching the camp in a sampan).

At 2245 hrs they gave us camp beds to sleep in and the others immediately turned in; at 2300 hrs I was writing my diary when our newly found friends rushed it to say we had to move immediately; the Wong Ching Wei people had found out we were there and were communicating the information to the Japanese; within 15 minutes we were on the move and were taken to two sampans; we went aboard and immediately set off, our escort being armed with all sorts of weapons - rifles, revolvers, Tommy guns and Mills bombs.

At 2345 hrs we landed on a shallow sandy shore and after 10 minutes walk up into the hills came to a house where we found comfortable asylum for the remainder of the night in a hay loft.

13th January.

After the first real night's sleep since leaving the camp, we woke much refreshed; we were not allowed out of the room all day, but our clothes were washed for us, hot water brought for our sore feet and we dispensed what few pills I had to the village sick. Final plans were discussed for our passage across Mirs Bay; the Reds did not want money but they did need quinine; we gave them all we could spare and persuaded them to take some money, with which they could buy supplies of quinine in Kowloon.

During the day we were warned to be ready to move at 5 minutes notice, and at 1730 hrs we had word that our Wong Ching Wei enemies were again on our trail, so off we went. About an hours walk up into the hills brought us to another small village (name not known) where we were to spend the night. Here we had our first introduction to what we later learned was an important part of the Red Organisation, namely a pep talk from the political officer covering the history, organisation and aims of the Red Guerillas.

14th January.

Before dawn we were up and washed, but before we could have our breakfast we had our 5 minutes warning and were on our way, in a northerly direction. Our escort was again heavily armed and all Chinese we met were stopped and questioned and warned not to mention having seen us to any one. At 0845 we came in sight of some junks lying near the shore of Three Fathom Cove, south east of Sai Kang. The spot was approximately 305689. We went aboard one junk which had a Bren gun mounted forward and which carried trench mortar shells and a large amount of .303 ammunition which we found later had been collected from the pill boxes on the information we had given two nights before. By 0900 hours we were off, making for Tolo Harbour. At 0930 hours we sighted three junks which our protectors recognised as pirates; immediately our crew cheerfully cleared the decks for action and sent us down below into a small hold. A small amount of spasmodic firing from our people caused the other junks to veer off and we were allowed up again as soon as the coast was clear.

In Tolo Harbour and Mirs Bay we saw no Japanese at all; the wind took us right across to Peng Chau Island (L4683, H.K. and New Territories 1/80,000); at 1600 hrs when off this island we tacked, and ran up to To Yeung (438912) arriving off the village about 1700 hrs. It was soon obvious that something unusual was happening ashore where a large group of people could be seen moving away from the village; some of these put off in a small boat and rowed over to a junk which was lying inshore and which immediately hoisted sail and made off, while suddenly from the group ashore a machine gun opened fire on us, a number of bullets passing through our stern. Our people did not reply because they thought the people on shore were friendly guerillas who had mistaken us for pirates.

After some more sporadic firing they moved off into the hills and we went ashore; To Yeung was a pitiful sight, the village had been completely pillaged and a dead body showed there had been some fighting on the outskirts of the town. What had happened was that the robbers in the nearby hills had heard that the "Reds" had left the village to come across to Sai Kang the day before; they therefore took the opportunity to raid To Yeung and at 1100 hrs that morning had swept in and taken off all the rice, food, pigs, poultry and blankets which they could lay their hands on. We had arrived just in time to see the rear guard leaving.

We went up to the Roman Catholic Mission where Father Caruso gave us some tea (all his milk and sugar had been stolen); but it was considered too dangerous for us to remain in the village for the night so we went back aboard the junk and put off shore for about 500 yards and anchored.

15th January.

At day-break we went ashore again and after a small meal set off with armed escort for Kwai Chung and then on to Tien Sum, arriving at 1600 hrs. It is interesting to note that our escort was under the command of Lau Pooi who 20 months later came into our B.A.A.G. picture again by capturing one of our W/T stations and five of our men including Lee.

16th January.

At Tien Sum we were treated royally and visited by all the Red guerilla officials from whom we learned much of their organisation; this experience was to be invaluable to me in my dealing with the Reds in the next two years. We had to wait at Tien Sum till dark for this was the point where parties were assembled to make the journey through the Jap lines. This rest of over 24 hours was a godsend to me, for my knee was causing me great pain whenever I moved.

At 1930 hours we moved to another part of the village and there met the rest of the party which, with escort, totalled about 50 people. We set off at a brisk pace all wearing rubber shoes, and any one making undue noise was immediately spoken to by the guards. My knee was causing excruciating pain and it was only the thought that there was but one night between ourselves and complete freedom that kept me going.

The night was clear, cold and moonless, and the country for the first part very hilly; our first stop was at 2100 hours. The second part was over flatter country and our second stop was at 2300 hrs; the next hour was to take us through the lines and we were handed over to another escort who refused to take such a big party; one woman had a child rolled up in a bundle on her back; for the last half hour the child had been crying and although its voice was muffled it made enough noise to set dogs barking in villages a good way away. The new escort refused to take the full party and we were the only people allowed to go on. With a smaller group they slackened the pace to suit me, and at 0115 hrs we arrived at Lo Ngan Shan in Free China.

17th January.

After just over a week of anxiety, uncertainty, hot days, bitterly cold nights, scares from Japanese and Wong Ching Wei Chinese, help from guerillas, sore and stiff in every limb, we fell asleep on tables in a school and slept soundly till daylight. Our guards had slipped away to spend the night in more comfortable quarters and with companions more to their liking; at day-break villagers brought us water for washing, and rice and chicken for breakfast.

Now that we were safe, I re-arranged all my belongings, putting certain private papers (which I had been carrying on my person) into my pack for easier carrying. The school was separated from the village by about 100 yards of paddy fields.

At 0900 hrs we had just started breakfast when a villager came in and said the Japanese were approaching the village. We hurriedly got our things together and rushed outside to find the whole country side one mass of fleeing people driving pigs and buffaloes, and carrying chickens, baskets, bags - all rushing from the village towards the river. We had gone barely a few yards when a false alarm was called. Against my better judgement I agreed to go back and finish breakfast, but we had just taken our packs off when the second alarm came. I grabbed my haversack but a Chinese lad told me not to waste time but to run. I thought he meant that he would bring my pack so that I could move quicker, so I left it in his care.

We slipped around the back of the school and joined the fleeing Chinese mob. Lee and I stuck together but we lost touch with Morley and Davies; we ran about 1/4 mile across the fields to the river; while we searched for a place to cross the river I looked back and saw a group of Japanese coming towards the school from the village. We wasted no further time searching for a shallow crossing place but waded across then and there, and gained the cover of a valley on the other side. There out of sight of the village we rested, and in the stream of fleeing Chinese we ultimately found Morley and Davies; they fortunately had saved their packs but Lee and I had both left ours. After a short rest we pushed on up the valley, then turned into a side valley, climbed the hill at the end of this and passed over into the next valley. We were all wearing army boots and the steep, slippery grassy slope was very difficult to climb, and before reaching the top of the crest some of the party wanted to rest; but we had taken enough risks and I made them pass over the sky line before resting; I then sent Lee along to the edge of the hill overlooking the river valley with the field glasses to see what was happening, and he returned to say that an enemy patrol was following up the valley behind us; we immediately moved further up into the hills and from this vantage point we could see the whole of the road leading north from the village of Lo Ngan Shan. To the north we could see a hill by the road with a white flag flying on the summit; this we knew indicated a guerilla post and the flag showed that the guerillas were in occupation; the enemy patrols had not gone in that direction apparently, so we made for the road to the north of this.

Once having gained the road, our going was much easier and early in the afternoon we arrived at Sun Hue (F3519) (H.K. and Canton 1/250,000). There we were met by an armed plain clothes man who took us to the Magistracy; since the Japanese by now must have known we were in the vicinity, it was considered unsafe for us to stay the night in Sun Hue, so we were sent on to Tai Shan Ha (F3227). On the way we met for the first time a Chinese military post where our names and ranks were taken and signalled through to Brigade H.Qrs at Waichow.

18th January.

The afternoon before, Davies had sprained his ankle; my knee was worse than ever and I could hardly put foot to the ground; Morley who had lost his teeth in Hong Kong was finding great difficulty with the food; we were in fact just about done. Lee was the only one really fit. Arrangements were made to take us on to Waichow by bicycles made for one but used by two, a method of transport which subsequent escapers along that route remember with much amusement.

I sent Lee back to Sun Hue to see if he could find out anything about our packs. At 1030 hrs the rest of us set off via Chunlung (F3228) for Waichow (F4145) arriving there at 1630 hrs. We were accommodated at the Wai On Hospital, and thus began the long association between this institution and the future B.A.A.G.

19th - 23rd January.

During this period we stayed at Waichow awaiting permission to continue our journey up the river; we called on the General and the Magistrate and sent a signal to the Ambassador in Chungking informing him of our arrival in Free China.

On the 20th Lee returned with the full story of the Japanese raid on Lo Ngan Shan and of our lost kit. It appears that the raiding party was 60 strong and when they entered the village they had no idea of our presence in the neighbourhood. Seeing a crowd of children around the school, the Japanese captain sent a squad of men over to investigate and they left the village just as we left the school. They found our kit, took it back to the officer in the village who immediately sent out three parties after us, one crossing the river and following us up the valley. They compelled one of the children who had been at the school to accompany them as a guide; he was some distance on ahead of them when he saw us near the skyline in the side valley. He very shrewdly went back and held the Japanese in conversation for a few minutes and then led them straight on up the main valley. Had we not gone over the skyline before taking our rest we would certainly have been caught.

The loss of our kit was a severe blow; besides being left with only what we stood up in, Lee lost all the notes he had made about the guerillas and I lost a list of the dead I had personally seen in Hong Kong together with my last war diary, a diary of two scientific expeditions I had conducted in Borneo and some articles I had written during 1940 and 1941 on "Japanese policy in the Far East". This latter would certainly be the death warrant of any one found by the Japanese with it in his possession.

23rd - 30th January.

During the long days and nights on the way from Waichow to Kukong there was ample time to consider plans for the relief of P.O.W. in Hong Kong, and by the time this part of the journey was over I had formulated a scheme which I hoped to be able to put before whatever military authorities there may happen to be in Chungking (at that time I was unaware whether there was any military organisation there or not).

Our arrival at Kukong was reported to Chungking by Lt.Col Owen-Hughes, who had been sent out from Hong Kong just after the outbreak of hostilities in order to liaise with the Chinese Army.

While waiting at Kukong for onward transport, word was received that Morley and Davies were to move on to Yunan, Lee was to go to the Commando School and I was to report at Chungking. I left Kukong by train on the 7th February and after a stay in Kweilin for over a week waiting for an aeroplane passage, arrived in Chungking on 17th February by Eurasia plane. Thus ended a 40 days journey - which included 10 days on foot, 8 of which were through enemy occupied territory - which completed the first organised escape from a P.O.W. Camp in Hong Kong into free territory, an escape which was rewarded with success only because of the continuous good fortune that smiled on us while in enemy occupied territory.

Thanks to Elizabeth Ride for sharing her father's report with us. After successfully escaping from Hong Kong, L T Ride went on to form the British Army Aid Group (BAAG), a military intelligence unit which operated in China between March 1942 and December 1945, originally as a branch of MI9. Elizabeth has compiled detailed records of the BAAG's activity.

Further reading:

- Maps of L T Ride's escape route in January 1942

- A second report of this escape, written by D F Davies

- The members of the escape group

- Photos of Shamshuipo Camp

- The British Army Aid Group

- The Elizabeth Ride Collection