Barbara Anslow had left Hong Kong in 1929, but returned in 1938 in time for her twentieth birthday. Here Barbara tells us what it was like to live in Hong Kong at that time, first giving us an overview, then quoting selected entries from her diary for 1939. Over to Barbara...

Background

On 5th November 1937 my parents told my sisters and I that we would all be going to Hong Kong again. We were living in Shotley, near Ipswich. I was almost 19, Olive 21 and Mabel 14. Both Olive and I were shorthand typists in the engineering firm Ransomes & Rapier, Ipswich. Mabel was still at school.

My Dad's brother wrote that my parents must be mad to take us girls to an area fraught with danger: the Japanese had attacked Shanghai in the summer of 1937, and shortly before Christmas they had shot up and sunk the U.S. Gunboat Panay on the Yangtse River. But we thought that was a long way away from Hong Kong.

So on 13th January 1938 we sailed from Tilbury on the P & O's Kaisar-I-Hind, one of the oldest ships of the line. Every so often smoke poured out of the funnel, and if you then happened to be on an upper deck, you would be covered with black smuts.

Arriving in Hong Kong

Some of Dad's colleagues from his previous tour 9 years ago met us, one was Walter Gill who invited us to tea after we had booked into the Metropole Hotel in Ice House Street where we were to stay until our Dockyard quarters were ready for occupation. When we arrived at the Gill's home and met Mrs Gill, she greeted us warmly and exclaimed to her husband 'Barbara doesn't look like a school marm!' apparently he had said this after meeting us at the wharf. Never mind that it had always been my ambition to be a school teacher, I didn't like the implication.

Our new home

Within weeks we moved into No.4 Naval Terrace, a ground floor flat in a block of 6 enclosed in lovely palm-shaded grounds adjacent to the Naval Dockyard and about a ten minute walk to the city centre. The entrance gates of the enclave opened on to Queen's Road, directly opposite a Sergeants' Mess where we later often played whist and bingo. There were barracks facing the back of our flat as well, known locally as 'The House With The Golden Clock', as such a clock graced the central building. We soon got used to the somewhat cheeky soldiers on the verandahs of the barracks.

There were four large high rooms in a row, each leading into its immediate neighbour; along the whole length of these rooms on both sides ran a wide verandah. Servants quarters and kitchen were at one end. Being on the ground floor, we were wary about burglars. Although an Indian policeman patrolled the grounds regularly throughout the night, Dad's revolver and two rings disappeared and were never found.

We employed a Chinese amah who did the cleaning, cooking, and laundry. We paid her HK$24 a month with $1.00 extra for firewood so she could do cook her own food on a chatty, a container used in the Far East for primitive cooking. It was considered too expensive then to allow the amahs to cook their meals on the stove where she cooked our meals, particularly as the amahs generally had relatives and friends visiting who would have meals with them. We also employed a 'makee-learn', a teenager who was learning to be an amah, her wages were $10.00 a month. Both had free accommodation.

Mum met up with former friends, and played mahjong with them; she also went to whist drives, and played tennis on the courts within the Dockyard. With no housework to do, she had plenty of time to meander among Hong Kong's intriguing shops, and to go daily to the market to buy fresh food.

Working again

Before long both Olive and I were employed as stenographers in the Hong Kong Government, she with the Imports & Exports Department and I with the Air Raid Precautions Department in the Secretariat. Until my Department moved to Happy Valley, I walked back and forth to work, also home for tiffin.

After work I sometimes did some private typing, some for an American lady author, May Mott Smith in the Peninsula Hotel; some for an English visiting businessman in the Gloucester Hotel. I remember a statement he put in a letter to his employers 'The large Aspro sign in lights in Central is the only real sign in Hong Kong.' (I wonder what he would make of the signs there now). He paid me HK$2.00 an hour.

Daily life

It was a trial when summer came: after tiffin, I always shed my dress and had ten minutes resting on my bed before returning to the office. My journey took me past the Naval Dockyard, where under verandahed buildings groups of Dockyard coolies sat on the pavement around playing cards (with strange, narrow ones); eating food brought to them by coolies carrying ready meals in baskets hanging from the bamboo stick across their shoulders; many smoking evil-smelling, very thin cigarettes. I can even now smell the aroma of all; this, plus an overlaying odour of some disinfectant white powder liberally spread around the pavements. Sometimes I would give in and take a rickshaw which only cost 10 cents. My wages in the Govt, were at first $150 a month.

There was then no air conditioning at home or in the office. We relied on overhead fans and desk fans. There were stifling mosquito nets over our beds. It was too hot to sit for long on cretonne covered settees or easy chairs. At work we would sometimes stick to our chairs with perspiration; our damp fingers became purple from the carbon paper. In a taxi you usually sat forward rather than lean back and stick to the car's upholstery. Nevertheless we ate hot meals, well washed down with fizzy mineral waters from the ice-box. Until we acquired a fridge with a freezer compartment, a coolie from the Dairy Farm Ice & Cold Storage Company brought us great lumps of ice in baskets hanging from either end of a bamboo pole across his shoulders.

Mabel was now at a shorthand and typing school; she would have rather started training as a nurse, but was too young. As she was not earning, I often used to treat her by taking her to the cinema with me. New films were shown at the Kings and Queens Theatre on the island; other smaller cinemas like the Oriental in Wanchai, and a couple of theatres in Kowloon etc. the Star, often screened older films and the seats were cheaper, so we often went to those. Mabel also started piano lessons with Miss Caroline Braga, whose elder sister Maud had been my teacher in the 1920's.

Dad's health worries

We acquired a large tent which we kept stored at Repulse Bay, we could then drive there and use the tent on the beach. One afternoon just Mum and Dad and Mabel went swimming there when the sea became rather rough. Mabel was a poor swimmer and used a rubber ring, and panicked when she was wafted out of her depth. Dad rescued her, but the current was so strong that he had difficulty towing her back to the shore. When he drove home he seemed perfectly OK but that night he became delirious, shaking and was really ill.

Dad was taken ill again just before Christmas 1938 and had a spell in the Naval Hospital off Queen's Road East, with a recurrence of the heart problem which in 1929 had resulted in him leaving Hong Kong before his tour was up. He seemed to recover and went back to work. His office in the Dockyard was only separated by a door from the always blazing hot generating station which he had to spend much of his day - not conducive to good health.

Worries about the threat of war, too

Although there was no real sign of political uneasiness in Hong Kong when we first arrived early 1938, it gradually became apparent that all was not as serene as it appeared. There were occasional blackout exercises. Training classes started for European women to become nurses for the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) to serve in time of war in the military hospital.

There were advertisements for men and women of all nationalities to train as Air Raid Wardens. Another nursing group was started, the Auxiliary Nursing Service (ANS), recruiting women of all nationalities to nurse in the civilian hospitals. My Mother joined this and looked good in her light grey cotton uniform with a white veil. Her training included a week's experience in the Queen Mary Hospital.

The Naval Dockyard still (as when we were children in the 1920's) ran weekly bathing trips for employees, but now they did not take us to the more distant beaches, there was a vague rumour that this was because of a defence boom across certain areas of the sea surrounding us.

During the crucial talks in Munich, I was undergoing a course of painful dental treatment. The headlines in the newspapers were about the threat of war. I used to wonder whether it was worth undergoing another agonising session when the world seemed about to explode into war, we felt that if war came to Europe it would immediately break out in the Far East as well. What a relief when the placards shouted 'Peace in our Time.'

Life outside work

In late summer the political situation in Europe was hotting up, but we in Hong Kong continued to enjoy life... swimming, dances, films, whist drives, tombola. When Mum, Olive and I came late on a hot night, the flat would be in darkness as Dad retired early and the amahs asleep. As soon as we put on the lights, flying cockroaches zoomed about the room, crashing into windows and lights until we attacked them with the Flit can. Should we have cause to go into the kitchen then, the light usually revealed giant cockroaches crawling about the surfaces.

Olive always had boyfriends. I had very occasional dates, but was far more interested in working on my latest story, so usually took myself to the pictures. (Unsurprisingly, someone said that I 'had the makings of an old maid' - which got back to me.) However I had a secret passion for one of Olive's boyfriends, Paddy Gill, Army, who visited us very often: this was before Paddy married Billie - the same Billie who is the mother of Ian Gill.

Selected extracts from Barbara's diary for 1939

Throughout January, the whisper of the threat of war in Europe could still be heard. I included in diary of 15th January a few extracts I'd had taken down in shorthand from the BBC radio news from London that night:-

'The diplomatic interpretation of the recent 'Hitler' talks is given prominence in more than one Sunday paper. The S.T. Correspondent says that the talks were of considerable importance, showing the frame of mind in which Hitler is laying his plans.'

And from the Hague 'Preliminary results of the investigations into the alleged shooting incident at the German Legation were reported to the German authorities, who expressed confidence in the Dutch investigations.'

And 'There is a very serious possibility of a conflagration sweeping the world,' said Mr. L.G. Assistant Secretary of War of (? ) last night, in support of President Roosevelt's Defence Programme. Munich has merely dramatised and emphasised the significance of the situation, the danger of which is recognised by every other country.'

On 22nd February diary says 'After Terrific raids in the New Territories yesterday (some bombs dropped in British territory, 1 Indian and 1 Chinese killed - Governor saw it for he was at Fanling), I was quite scared when air raid warning went this afternoon while I was taking dictation.'

Next day the diary adds 'Japs have apologised for the bombing.'

25th February. 'Jap planes supposed to be on the Border again this morning.'

15th March. 'Goodness knows what's going to happen to the world. Headlines say 'Germany and (?) dismember former Czechoslovakian Public. Germany has taken the Czech people under the protection of the Reich.' and an agreement on these lines was signed by Herr Hitler, Pres. Hacha and M. Chvalovsky, and that 'the autonomous development of Czech national life will be guaranteed by the Reich.'

17th March. 'U.S. Says that 1939 should be the crisis year.'

5th April. 'British Consul in Egypt was stoned to death because agitators said that King Ghazi (yesterday killed in a car accident) was murdered by the British.'

7th April. 'Italy invaded Albania, which is supposed to mean war.'

My colleague Barbara Budden and myself came home from work in a sedan chair (one each) my first such experience, it was a real shake up.

Mabel had two weeks' work at Government House writing names on cards to a Government Garden Party, she had lovely handwriting, how pleased she was to be earning!

26th April. 'Quote from London radio broadcast:-

'If Hitler utters threats, they cannot affect the present situation.

If he utters assurances, they will not be believed until put into effect.

If he utters abuse, we can afford to ignore it.'

Mum passed a course of 'Home Nursing.'

6th May records that King and Queen went to Canada on Empress of Australia. (The cabin which Mum, Mabel and I shared with several others on the Empress of Australia in 1945 was part of the Royal Suite the royals occupied.)

Diary also says 'Would like to write a poem about 'living bravely', the idea being to go on living as normally and idealistically as possible, even though we don't live in normal times.'

24th May. 'The P & O Ranpura was stopped and boarded by a party from a Jap destroyer about 9am today. The cheek seems incredible. HMS Duchess was near and soon arrived and the Japs were ordered to leave, which they did.'

Had nails done (80 cents) and eyebrows (70 cents). Also lipsticked and rouge (family disapproved). These innovations were my attempts to make myself more like my sophisticated colleagues at work, although I never managed to become a smoker as some of them were.

14th June. 'Imagine having got almost halfway through this year's diary (without war). In January I wouldn't have dared thought of it. Someone in office came in with great ideas that Britain would declare war on Japan within the next 2 days!'

15th June. 'Trouble in Tientsin, according to placards. But I like to believe it's all bluff.'

19th June. 'Refuse to stain diary with writing about it, but I feel like praying for an earthquake up there.' (This isn't explained!)

About this time the Director of Air Raid Precautions, Wing Commander A.H.S. Steele-Perkins (my boss) founded a mini newspaper called the ARP Chronicle. I started writing articles for it and dared to show one to him. He laughed and said 'Anything will do to fill it up.' which I recognised as not very encouraging.

We now had a chow dog, a talking mynah bird, and a monkey called Paddy. Incredibly, one day we took Paddy with us to Repulse Bay. He was a great attraction to the children around us on the beach.

I was now attending the boss's ARP weekly meetings to take the minutes, and felt very important. As ARP work extended a second stenographer joined the department, Rosaleen Grant, we became great friends.

The world was still teetering. Diary on 11th July says 'Germans have incited Chinese to mob the British Consulate at Tsingtao.' Dad wasn't well again, but despite seeing the doctor he went on working, and 'worrying the life out of Mum by not obeying doctor's orders.'

18th August diary records, '17 Jap bombers over Stanley today', but doesn't elaborate.

At that time I started taking a course to become an Air Raid Warden, and witness my boss DARP demonstrating how to deal with incendiary bombs: also went through the pseudo 'gas chamber' on ground floor of ARP HQ in Happy Valley.

22nd August. 'Germany signed a pact with Russia and nobody seems to know why.'

Next day, sandwiched between a report of how my new dress seemed when I tried it on at the tailors, and about a new story I was writing, is 'A nephew of Wang Ching Wei (now called Arch Traitor of China) was shot dead in Wyndham Street about 8.30 last night.'

24th August, Thursday. 'While at work, Mum phoned to say we can be evacuated on the Ettrick at noon on Saturday at noon on Saturday if we wish to go. Neither Olive nor I want to go. Paddy Gill came over in evening and he was like a pillar of confidence. I'm not frightened because I honestly don't believe things will happen here.'

25th August. 'Local news is supposed to be better, though the First Battery (of HK Volunteer Defence Force) has been called up. Conditions at Home - Emergency Powers Bill passed etc. Ettrick is now not sailing Sat - date indefinitely postponed.'

Still a strained situation in the colony, as in the office that Saturday (we worked Sat mornings then) staff were told to come back in the afternoon. Despite the anxieties, Mabel and I splashed out on a taxi to Repulse Bay on Sunday to swim, and bused back.

29th August. 'Hong Kong is not going to be attacked by the Japs, according to the press. Matters at Home seem very bad. Opinion here seems to be that war WILL come here eventually.

1st September. 'Terrible headlines - 'German planes bomb Warsaw.'

3rd September, Sunday. Olive went to work, I went in about 12....

About ten minutes after writing diary, there came a radio relay from England - we are at war.

Olive and I went to the pictures to see 'Bachelor Mother.'

The next day, Monday, was a public holiday, but we stenographers were recalled to offices in the morning. Athenia sunk off Scotland, most saved. Wireless interference in news.

8th September. HMS Duncan is in, so Olive went out with her current boyfriend Fred.

Up to outbreak of war, armed services could wear civilian clothes when off duty. But now they they had to wear uniform all the time.

10th September. 'Dad said we may go to Singapore.' In that case I would prefer to stay here.'

18th September. HMS Courageous sunk but there are survivors.

Despite the European war, social life in Hong Kong went on as usual, although we often worked overtime, and training of nurses and Air Raid Wardens continued, and practise blackouts.

We could hardly believe it when we saw newsreels showing schoolchildren being evacuated from towns in UK to the country: more horror when we heard HMS Royal Oak had been sunk.

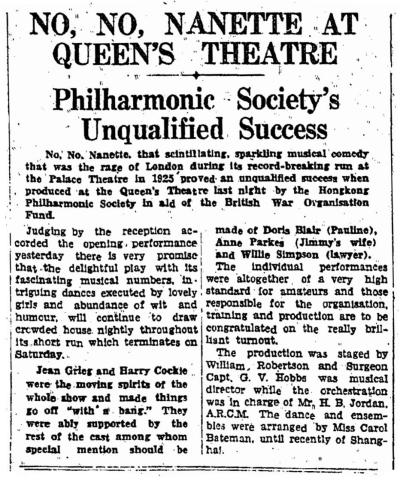

Olive, Mabel and I joined the local Philharmonic Society which was short of girls for the chorus of 'No No Nanette'. We thoroughly enjoyed this new dimension to our lives which involved frequent rehearsals at the China Fleet Club and at the Queen's Theatre, all starting at 9pm. It was finally performed at the Queen's shortly before Christmas.

5th October. 'Went to be fitted for gas mask in Dockyard with Mum Mabel and Olive.'

28th November. "The Rawalpindi (on which we had traveled to Hong Kong in 1927) gave battle to two German battleships before going down.

30th November. Went to see documentary film 'The Warning' with ARP staff.

1st December. 'My 21st birthday. I have everything I want. Mum and Dad gave me a book case, Olive and Mabel some books, the girls at work an ornate camphorwood desk! Dad gave me $10 - I bought The Herries Chronicle. Other presents, a Parker pen, an inkstand and scent. Mum had a fantastic cake made in the form of an open book. No men at my party, just my office girlfriends.'

Next day, Paddy the Irish charmer, called in to see Olive; he had just returned from Shanghai and brought presents; he gave me a pale green soft angora cardigan.

18th December. 'Graf Spee scuttled outside Montevideo though the crew were taken off first, but her commander stayed aboard - brave man.'

20th December. 'Rosaleen and I took our lunch sandwiches to eat in the Botanical Gardens.' Two Asiatic tourists sidled around with cameras and asked us in broken English if they could film us sitting on the bench as it was an artistic picture. The men said they would send us copies if we gave them an address, so we agreed. When they told us they were Japanese, we wished we hadn't, as they could have been photographing parts of Hong Kong as spies. We did eventually receive copies of the photo which I still have somewhere.

I had a strange date at this time: one of Olive's ex-boyfriends, Harry Chalcraft, asked me to have a drink with him in Jimmy's Kitchen near the Queen's Theatre, he was in a very bad way as he was deeply in love with Olive still, he wanted to talk to someone about Olive, so I filled the bill. We sat there for hours, he smoked and talked, I've never forgotten the pain in his eyes, he just needed a listener. (He survived the war, married in UK and with his new wife came to visit us in 1946.)

In 1939 I recorded seeing 85 films !

Many thanks to Barbara for sharing her memories and diary with us.

Further reading:

- Barbara has previously shared her memories of life in Hong Kong in the 1920s.

- She has recently published her diaries of Hong Kong's war years, 1941-45, in book form. The book, Tin Hats and Rice, is available to order here on Gwulo: