The following text was given as a lecture by Mrs L. I. Puckle to the Churchstoke Womens Institute.

I feel very much honoured that you should have asked me to come and tell you about our experiences at Stanley Internment Camp and I hope I shall be able to give you some picture of the life lived there. This is the first time I have ever spoken in public, so I hope you will forgive any shortcomings and make allowances for my lack of experience.

When hostilities broke out in Hong Kong on December 8th 1941 my husband and I were living at Repulse Bay Hotel, on the south side of Hong Kong Island. He was then Director of Air Raid Precautions and I had joined the Auxiliary Nursing Service, which was the civilian equivalent of the V.A.Ds.

On that fateful day my husband was rung up at 4 a.m. by the Military Headquarters and told to mobilize the Corps of Air Raid Wardens immediately. At breakfast time we heard of the bombing of Pearl Harbour and the declaration of war between England and America and Japan. The Japanese had already begun to bomb Kai Tak, Hong Kong's civil aerodrome, and at 9 o'clock I was called up and told to report at once to the French Convent Hospital, to which I had already been posted. Events then moved so rapidly and relentlessly that one had at times the feeling that one was struggling against a huge tidal wave which would eventually engulf one. The work of the Hospital was carried on at high pressure to the sound of distant gun fire, which became louder day by day until the noise, especially at night, became terrific. On the 12th December Kowloon, which lies on the mainland opposite Hong Kong, was captured by the Japanese, who sent an envoy to the Governor, Sir Mark Young, offering honourable terms if the British would surrender. This offer he rightly and defiantly refused and the siege continued. Very soon the Japanese had landed on the Island, quite near to our hospital, and as there was a British battery on the hill just behind us and a machine gun post at our front gate, we were in the direct line of fire and the buildings were soon badly knocked about. One of the nuns was killed and a British doctor and four Chinese Staff nurses and a coolie were badly wounded. Soon the Main Hospital was so badly damaged that the patients had to be moved into the Auxiliary Hospital where I was working. Soon that was untenable and, with the casualty clearing station, had to be evacuated. The Medical Officer in charge telephoned to the Director of Medical Services and suggested, that as the situation was so precarious, the hospital should be cleared, the conditions being almost impossible. The reply came that we were to move the patients to a place of safety and carry on. This order gave rise to some caustic comment, as there was no place of safety, but the patients were eventually moved into the Convent Chapel and, without water, gas, electricity or telephone the hospital was re-organized, an emergency operating theatre set up in one of the side chapels and we carried on. We were now surrounded by the Japanese forces and shelling gave place to machine gun and rifle fire, but as we were cut off from our own people, we had no news as to how the hostilities were going in other parts of the Island. Christmas Day came, one of the most perfect days I ever remember, clear and calm and sunny, and the din and racket of war was succeeded by an unnatural and rather sinister stillness. No sound of gun-fire or bombs, only an occasional Japanese plane circling round overhead in the cloudless sky. The uncanny silence was more unnerving than the noise of war, and we waited uneasily for news. Next day we were horrified to hear that Hong Kong had fallen, unconditionally surrendered. It was a thunderbolt to us, as in spite of bad conditions, we all expected and hoped that the Island would have held out for some weeks longer.

This in no place to discuss the military aspects of the capture of Hong Kong, nor am I qualified to do so; but, put very briefly, I should say that it was mainly due to overwhelming superiority in Japanese man-power and complete lack of naval and air support. All our ships and planes had previously been sent down to help in the defence of Singapore and very inadequate anti-aircraft barrage was our only protection against Japanese planes.

I shall never forget my sensations when the first party of Japanese soldiers came into the French Hospital, armed with revolvers, rifles and Tommy guns, and slouched through the rooms at their leisure. It was hard to realize that this slovenly, dirty, villainous looking rabble were our conquerors.

The fact that our hospital was French property and was flying the French flag saved us from some of the worst excesses which took place in some of the other hospitals, where the Red Cross did not save the nurses from horrible ill-treatment. For a time we were, however, warned not even to go out into the garden and for the more highly strung night duty was an ordeal.

A month of anxiety and uneasiness followed, filled with rumours as to our eventual fate, and at last on the 29th January 1942 we were told we were leaving at 2 o'clock for Stanley. We were issued with a plate, mug, knife, spoon and fork, the sheets and pillow-case off our bed and two blankets, and this for many of us was our household equipment for the next three and a half years.

On arrival in camp, where I rejoined my husband after two months separation, we began to take stock of our new surroundings. Stanley is a long and narrow peninsular running out into the sea on the south side of Hong Kong Island, and on turning off the main road you pass through a cluster of modern houses, belonging mostly to wealthy Chinese, but now looted and deserted, and come to a small Chinese fishing village. Passing through that you reach St. Stephen`s College, a fine modern school for Chinese boys, belonging to the Church Missionary Society and run by an Anglo-Chinese staff. This is followed by some buildings, which before the war housed the staff of the Hong Kong Prison, and then the Prison itself - one of the most modern In the British Empire and under the British administration, conducted on the most humane and enlightened lines, but during the Japanese regime it was the scene of untold horror and suffering, where many British, Indians and Chinese were tortured and done to death. Still further along the peninsula and almost at the end, is a large fort with barracks, officers` mess, church, school, stores and so on, with many batteries of large naval guns, guarding Hong Kong from attack by sea.

But it is with St.Stephen`s College and the Prison Staff Quarters that we are concerned, as it was in those buildings that 2,500 British subjects - men, women and children - were interned for three and a half years. We were very lucky compared with some other camps, as our surroundings were most beautiful and we had quite a reasonable amount of space to walk about in outside, but once inside our quarters it was a different story. We were terribly overcrowded and the lack of privacy was for many of us the worst trial of camp life.

Stanley Peninsula was the scene of some of the fiercest fighting in Hong Kong, and many of the buildings in camp were badly damaged by shell-fire. Also, the whole place had been thoroughly looted, first by the Japanese and then by the Chinese from Stanley village, so that it was a scene of devastation when we arrived.

Life in those first weeks was rather a grim affair. Many women in camp had lost either husband or son in the fighting and others were still uncertain as to the fate of their relatives; practically everyone had lost all their worldly possessions and knew their homes to be looted and wrecked. Most of us were suffering subconsciously from shock and from a sense of unreality. I, myself, felt as though I were living in an unpleasant dream, from which I should shortly awake, to find myself once more in our charming room at Repulse Bay Hotel. Anything further removed from the comfort and beauty of Repulse Bay Hotel than our present surroundings it would have been hard to find. My husband and I were allotted a half share of a room in the Indian Warders` quarters, which the Indian occupants had just vacated. The room, which was 10 ft, 6 inches by 13 ft, was completely devoid of all furniture except for four beds (two of which belonged to our room-mates) with concrete floor and dingy whitewashed walls, very dirty and, as we afterwards discovered, verminous. The struggle to keep down, for we could not wholly eliminate, bed-bugs was one of the nightmares of camp life, as we had no disinfectant or insecticides to deal with these pests. This unattractive apartment we shared with another married couple, without even a curtain to screen us from each other, and the close proximity and lack of privacy at times became almost unendurable. Only the realisation that one had to endure it, that there was no alternative and no escape, kept one going. There was no communal dining room or living-room - we ate, slept, worked and cooked in the one room, and if you were so unlucky as to fall ill you lay on your sick bed there too, while the daily life of the room went on around you. If we had been so fortunate as to secure a room to ourselves, as some married couples did, camp life would have been robbed of half its horrors.

There was also complete lack of organisation in the early days. Nobody knew what to do or where to go, the food was appalling, and as there was no communal kitchen near our quarters at first, we had to go a long way to fetch our food and stand in a queue in the cold, while hundreds in front of you were served. We also had to queue up for hot water for our tea – there was none for any other purpose – and frequently after an hour`s wait in a piercing wind when you at last reached the head of the queue, you were told to come back in an hour`s time – the water was all used up and the boiler was empty.

The food in those first weeks was simply unspeakable – all we were given was sodden, badly cooked rice, with a small heap of fish-bones and skin dumped on top, and a few coarse rank green vegetables. This was served to us twice a day, at eleven and five. In addition to this, we had a tiny slice of bread, often mouldy.

The weather was cold and wretched and we had no heating of any sort. Many of us had not enough winter clothes and blankets to keep us warm; and this miserable diet began to tell its tale in pinched faces and hollow eyes, and the deficiency diseases, which were such a distressing feature of camp life, began to make their appearance; diseases such as beri-beri, pellagra and worst of all central blindness, all of which were due to the lack of one or other of the vital vitamins in our diet. Doctors and dieticians worked nobly to counteract this vitamin deficiency, but they were terribly handicapped by the lack of proper drugs. Dysentery also broke out at this time and for a while there was an epidemic of it, aggravated by the coarse badly cooked food we were given.

It was when things were at this low ebb that we heard of the fall of Singapore and our hopes of release faded. On looking back over the three and a half years of our internment, this time stands out in my mind as the blackest period of all, but even in those grim days the morale of the camp was amazingly high, and there were inspiring examples of courage, kindliness and selflessness.

Camp life seemed to intensify whatever characteristics a man or woman possessed. Those who were unselfish and courageous became even more so, while others lost all self-respect and gave way to theft, scrounging, immorality and back-biting.

In this connection I should like to say a word about the members of the various missionary societies, of whom we had many in Stanley. One often hears missionaries criticized, but I can only say that they were a shining example in our internment camp. Almost without exception they played their part in the communal life as doctors, nurses or teachers according to their capabilities. They were cheerful, helpful and uncomplaining, and undertook readily any unpleasant or distasteful task which had to be done. As a body they made a most noble contribution to the well-being of the community and their selfless work earned the admiration and respect of us all.

By degrees conditions in the camp improved; the weather became warmer; after endless protests to the Japanese the food was increased, kitchens were improvised in different parts of the camp and a very small loaf of bread was added to our daily rations. Little by little from being a bewildered and disorganized rabble we became a community.

Tasks ware allotted to different people according to their strength and capacity, and in time the camp became a self-supporting township with church, school, hospital, social services and so on. The church was one of the first things to come into being, when in the very early days the ministers of the different denominations met and formed themselves into a body called the United Churches. Services were held every Sunday in the big hall of St. Stephen's College, a choir was started, and the church became a very living inspiration to those who attended the services.

Schooling was begun too, and under immense difficulties, owing to lack of space and proper equipment, the task of educating the children in camp was carried on.

A hospital, and clinics in different parts of the camp were opened, and I would like here to pay a very warm tribute to the wonderful work done by both doctors and nurses in Stanley. Although, like all the internees, they were suffering from malnutrition and lack of vitality, with incredible difficulties to contend with owing to lack of medical supplies and drugs, they gave freely and unsparingly of their best. Many of us owe to the medical and nursing profession in Stanley a lasting debt of gratitude, and I can pay them no higher tribute than to say that they lived up to the noblest traditions of their calling.

Social services were organized to distribute any clothing and comforts which the International Red Cross were able to send into the camp, and although much criticised, as all social services are, they too did good work.

Libraries, too, were started in different parts of the camp, and no words can say what a boon they were. Those who had brought books into Stanley with them, handed them in for the use of the community; and the International Red Cross representative, a Swiss named Zindel, managed to buy some of the books which had been looted from private libraries in Hong Kong and sent them into camp. After a time a very fair library was assembled, and it provided endless interest and amusement for what would otherwise have been dreary and profitless hours.

Lectures, too, were started on a wide variety of subjects, and we were lucky in having all the teaching staff of the Hong Kong University with us, so that we had highly qualified and well-trained speakers to lecture us on subjects such as literature, biology, psychology and so on. Classes were also started in languages, both European and Asiatic, and in subjects such as marine and electrical engineering and navigation, and though greatly handicapped by lack of proper textbooks, much good work was done.

Nor was lighter entertainment neglected. We had a lot of extremely talented people in camp, and very soon concerts of both light and classical music were in full swing, and an Amateur Dramatic Society gave some really remarkable performances, overcoming successfully immense difficulties with regard to costumes and scenery. The plays ranged from Shakespeare to musical comedy and ballet, and not only provided many a pleasant hour`s relief from tedium, but gave us a fresh topic of conversation, which was all too apt at that time to centre on food, or the lack of it, and the delinquencies of one`s room-mates.

A Japanese sponsored newspaper was allowed into the camp, but the news was so distorted as to be almost valueless, and it was obviously intended less to convey information than to depress our spirits and lower our morale. This, I am glad to say, they did not succeed in doing, as the paper was treated rather as a joke, and we had our own underground sources of information. Nevertheless, nerves were over-strained owing to the lack of food and the unnatural overcrowded manner of living; and in addition to our bodily discomfort there was the constant gnawing anxiety as to what was happening in the outside world, from which we were cut off as by an iron curtain, and a continual longing for news of our people at home and those fighting in different parts of the world. Letters did come into camp, but they were few and far between, and they were anything from six months to a year, and even two years, out of date. Only a small fraction of the letters written ever reached us, but those that did come, brief and out of date as they were, were a tremendous joy. We were only allowed to write one postcard a month ourselves, of twenty five words, and we had to be careful to omit all references to the Japanese and their treatment of us.

Even those women whose husbands were in the Prisoner of War Camp on the Mainland, a few hours` journey away, were only allowed one postcard a month, which often arrived months after it was sent; and in many cases wives at Stanley only heard of their husband`s death a year after the event. The suffering caused by this callous indifference on the part of the Japanese was intense and quite needless.

One of the events which most internees in Stanley will look back on with most pleasure, was the arrival of the first food ship in Hong Kong, sent under the auspices of the International Red Cross. We were not only suffering continually from hunger, but our food was monotonous and tasteless in the extreme; and the arrival of these parcels, with delicacies such as chocolate, cheese, marmalade, condensed milk and so on, as well as cases of bully beef, tea, sugar, cocoa etc., sent our spirits soaring, and great was the rejoicing in the camp. On the same ship as the food, came a most welcome supply of warm clothing, which was a tremendous boon as it was a problem to keep oneself warm in winter. You at home had your troubles too, with limited clothing coupons, and short supplies of most things in the shops; but at Stanley we not only had no means of replacing the worn-out clothes, but we had no stocks of old clothes to fall back on, as most of us had only been able to bring one suitcase into camp; and any clothes left in houses in Hong Kong had of course been looted and scattered to the four winds. My husband and I were among the few lucky ones, as after six months in Stanley our clothes were sent in from Repulse Bay Hotel, and were simply invaluable as we were not only able to clothe ourselves adequately and help out our friends, but when funds ran low, we were able to raise a little money by selling something. But few people were as fortunate as we were, and most were put to all sorts of shifts to keep themselves clothed and shod. Shoes were a continual headache for most people, and in the summer many of us, even among the women, went barefoot, but the winter was another matter and much more difficult. Wooden sandals were a great help, if you were lucky enough to find a suitable piece of wood to make them – my husband made me a pair in the early days which I found invaluable. The children presented the biggest problem in many ways, as they were continually growing out of their clothes and shoes, and it was a difficulty to keep them properly clad.

We were terribly short of mending materials too – needles, cotton, tape, darning wool, buttons and so on – all the small necessities of life which one takes for granted usually, but which can complicate matters so desperately when they are unobtainable. To break a needle was a major disaster, and towards the end of our time, when even the Welfare Committee were not able to get any supplies in from Hong Kong, one darning needle and one ordinary sewing needle and three reels of cotton, black, white and khaki, were issued to the Welfare Officer in each block (containing about a hundred people) and if you wanted to make or mend anything, you had to apply to her for the needle and cotton!

I must say people showed extraordinary ingenuity in contriving out of most inadequate and unlikely material what they were not able to buy, and most attractive buttons were made out of tooth-brush handles, hats were woven out of rushes, and really lovely children`s toys were made out of tins and empty cotton reels. At one time an exhibition was held of any articles made in camp, and the range and finish of the exhibits was really astonishing considering the lack of suitable materials and tools.

You are probably surprised that in all this account of our captivity there has been so little mention of our captors, the Japanese. As a matter of fact, one of their few redeeming features was that they did not obtrude themselves unduly into our daily life, and left the running of the camp to a certain extent to the internees themselves; though permission had to be obtained for every alteration in camp rules, and for the holding of every meeting or entertainment, which permission they often withheld, just to make themselves unpleasant and to let us know who was master. The Japanese are a petty-minded people, and love to show their authority and power in stupid and irritating rules and regulations.

The guards stationed round the barbed wire perimeter were at first Indians, and then later, when they were suspected of being too much in sympathy with the internees, their place was taken by Formosans. Unlike some camps, there were no atrocities at Stanley, though face slapping and knocking down were of common occurrence; and people were frequently taken to the Japanese Administration headquarters and beaten up for some minor offence.

The Japanese are great sticklers for etiquette and are accustomed to greet every soldier with a very low bow from the waist; to them, the soldier is the representative of their Emperor, who, as you know, they regard as semi-divine. This custom they expected us to confirm to, and, as you may imagine, it was a great thorn in the flesh to us all, and led to endless trouble and face slapping.

But though not always in evidence, the Japanese were a sinister and menacing background to our lives, affecting every moment of our day, and obstructing every effort to improve our lot. Nothing that went on in camp was hidden from them, as their spies were everywhere, and our movements were watched through field-glasses from the Japanese Headquarters which was situated up on a small hill.

But though there were no atrocities in the camp itself, the case was far otherwise in the prison, which as I have already said, was quite close to the camp. There, men were put to the most horrible torture, to extract information from them and make them incriminate others, and internees living in the building nearest the prison could sometimes hear the screams of the unhappy men, who were suffering at the hands of their torturers. Two men, whom I knew personally, died in Stanley Gaol of starvation and neglect, for no other crime than that they had provided money from the Hong Kong Bank funds, to buy food and medical supplies for the P.O.W. and Internment Camps in Hong Kong.

In 1943 there was at one time almost a reign of terror at Stanley, when the Japanese Secret Police swooped down on the camp, and arrested men and took them away – sometimes they returned after some weeks, forced under threats of re-arrest not to speak of their experiences to anyone; but very often they were not seen again. In October 1943, eight Englishmen were beheaded at Stanley, on a beach near the camp, in full view of a bungalow where the wife of one of the victims was living. These executions aroused the greatest horror and indignation in camp; but orders were given by the Japanese that no religious services were to be held for the executed men and there were to be no public demonstrations of sympathy to their relatives, under threats of severe punishment.

No account of camp life would be complete without at least a passing reference to the black market, which flourished exceedingly at Stanley. The black market kings lorded it over their less enterprising, though more honest, fellow prisoners, and lived like fighting cocks, while the rest of us were existing on rice and coarse vegetables and evil-smelling dried fish. All black market transactions were in theory strictly forbidden, and we were threatened with all sorts of dire penalties, including imprisonment, if we were caught buying or selling black market goods. In actual fact, the Japanese were the organisers of the whole racket, and it was only when they suspected that they were being double-crossed by some of their own agents, that they made any trouble. Supplies for the black market, almost entirely foodstuffs and cigarettes, were actually brought in on a Japanese lorry, under the eyes of the sentries, driven up to Headquarters, unloaded by the guards, and distributed quite openly to their agents, who then disposed of them at fantastic prices to the hungry internees. To get money to pay for these luxuries (an occasional egg, a few peanuts, or a little Chinese brown sugar) we had to sell any little valuables and trinkets we still possessed; a steady stream of watches, fountain pens, cigarette cases and wedding rings passed into the hands of the Japanese; in return for which we were given worthless paper currency, which in its turn went back into Japanese hands to pay for the vital foodstuffs. Very few of the married women in camp still had their wedding rings when they left Stanley; those who had not had them snatched off their hands in the early days of the Japanese occupation, sold them to get food and were wearing a substitute made from a ten cent piece. I am still wearing a ring made in camp from a sixpence, to replace the platinum one which I was obliged to sell. You can imagine how greatly it went against the grain to sell our cherished possessions to the detested Japanese, but much as one must condemn the black market and those who operated it, I can only say that bad as it was, the extra food which it provided helped to keep many of us alive who would not otherwise be here today.

I have often been asked whether the time hung very heavy on our hands. To this, I can truthfully say “No”. We were so busy with a hundred and one things which had to be done, our cleaning, washing, mending and making, as well as communal work and endless standing in queues, that the day seemed all too short in which to get everything done. Most people who were fit enough to do so, did some communal work. My husband at one time was in charge of the communal kitchen in the Indian Quarters, and I worked as a scullery-maid in the Diet kitchen where we cooked for children and invalids.

Queues were one of the features of camp life. We had to queue up for our meals, for hot water for our tea (there was none for any other purpose, and I did not have a hot bath for three and a half years!) for the clinic, the library, our entertainments, the canteen and a hundred and one other things. Many were the hours spent standing in queues in Stanley and the wily ones soon learned to take a book and a stool and make the best of a bad job. But though the days passed quickly enough the time of our imprisonment seemed very long, and at moments one wondered whether our release would ever come. As the years went by conditions became harder, the food more scarce and poorer in quality and the electricity was reduced steadily until finally it was cut off altogether. For the last year of our captivity we had no artificial light at all, and when the daylight failed we sat in the dark. This was not so bad in the summer, as we were allowed to sit outside until 9 o`clock, but in the winter it was dreary beyond words as we huddled on our beds in the dark, clad in our outdoor clothes for warmth and with no distraction but our thoughts. Even unfettered conversation was not easy, owing to the continual presence of our room-mates. Worst of all, however, was the water shortage. The pumping at the reservoir was done by electricity and when the electric current failed owing to lack of fuel, we had continual trouble with the water supply. At one time the water mains were only turned on once in five days and as we had no containers in which to store water, the discomfort and inconvenience this entailed were beyond words.

The attitude of the Japanese too became harsher and more domineering, rules and regulations were tightened up and penalties became more severe for any disregard of orders.

But by the beginning of 1945 our spirits began to be buoyed up by an ever-increasing hope, as the news from Europe became more and more cheering and we felt that the end was in sight. V-E Day came and was hailed, not with any outward demonstrations of joy, but with deep heartfelt thankfulness that in Europe at least the war was over. Even then, many people in camp thought that it would be at least six months before Japan was beaten, and one hardly dared hope too much lest once more we should be disappointed. By the beginning of August hopes ran very high, and it soon became evident that our days in Stanley were numbered. The Psalmist said long ago “When the Lord turned the captivity of Zion, then were we like unto them that dream,” and that lovely verse rings true in the ears of any who have themselves been captives. When we heard that the days of our captivity were at an end, then indeed were we also “like unto them that dream.” There was no outward excitement, no wild cheering or singing – only a dazed incredulous wondering whether it was really true that this moment for which we had longed for so many years had come at last.

For two days after the announcement of Japan`s surrender, before the British had landed on the Island and while the Fleet were waiting outside Hong Kong waters for orders to take over, planes from the aircraft carrier “Indomitable” circled round the camp, dropping supplies by parachute, and demonstrating to the Japanese how swift would be the retribution if they attempted any reprisals on us. By this time the first bewilderment and shock of our release had worn off, reaction had set in, and pent up feelings of pride and gratitude were released in wild cheering and frantic waving of hands and handkerchiefs, as each plane swooped low over out heads.

On the 28th. of August, Admiral Harcourt, attended by some members of his staff and accompanied by a jeep manned by fully armed blue-jackets arrived at Stanley; and at a brief but very moving ceremony the Union Jack was hoisted once more, accompanied by the flags of all the Allied Nations. It may interest you to know that the flag hoisted at the ceremony was the same one which was flying over Government House when Hong Kong surrendered, and the Japanese ordered a member of the Government House staff to haul it down and destroy it. He hauled it down, but instead of destroying it he secreted it somewhere and managed to smuggle it into Stanley, where he kept it safely hidden until the great day when he had the honour of hoisting it again over a liberated Hong Kong.

Little remains to be told now except that for the remaining four weeks of our stay at Stanley we were under the care of the Royal Navy, and that will be enough to tell you that good food and every possible care and consideration was given us. Also for the first time for 3½ years my husband and I had a room to ourselves and no one who has not lived day in, day out for years in one room with strangers knows what unutterable relief and release from nervous strain that meant.

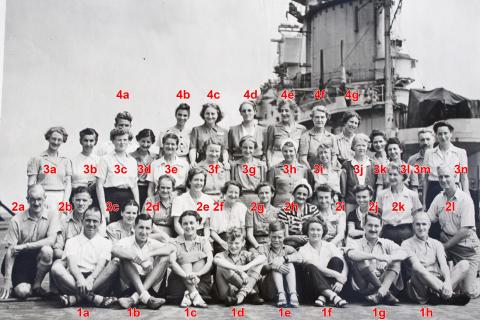

A very happy voyage home on the aircraft carrier “Indomitable”, where we were showered with every possible kindness and care by the entire ship`s company, and also by Red Cross Representatives at every port at which we touched brought us back to this country and to the end of our troubles.

I would like to say in conclusion that for most of us at Stanley, and I am sure I can speak for P.O.W. and Internment Camps everywhere, the worst feature of our captivity was the thought that we were cut off from all part in the great struggle which was going on all over the world, and in which you at home played so vital a part. If I may, I would like to read you a few lines written by a friend of mine, himself an internee in Shanghai, which express far better than I can our deep gratitude at the warmth and kindliness of our welcome home.

We played no part in war. No worthy deed

Our past enriches. From behind our walls

We only waited: in our country`s need

Impotent, useless: No response to calls

Our lot, alas, debarred us any share

In Epic Victory, so dearly won:

No pride is justly ours: no breast can wear

The honoured symbol of a deed well done.

Now we return: and with no claim we find

From generous hearts a sympathy to cheer:

A warming welcome, strengthening and kind

Bestowed by those who suffered trebly here.

With grateful hearts but conscious of a debt

That all our striving never can requite

We heed the lesson: never to forget

Brave souls who changed our Darkness into Light.