| ( Video ) National Archives - Description |

| https://archive.org/details/NPC-14645 (00:00 - 01:59) |

| 1) MS British Avenger landing on the deck. 2) HS Japanese with a Samuri sword in his hand walks down the flight deck. |

| ( Photo ) IWM - Description |

| https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205161627 |

| Watched by a Marine sentry, envoy Makimura walks back down the flightdeck of HMS INDOMITABLE to the plane waiting to take him back to Kai Tek airfield, Hong Kong. He had been discussing the surrender of the city. |

|

|

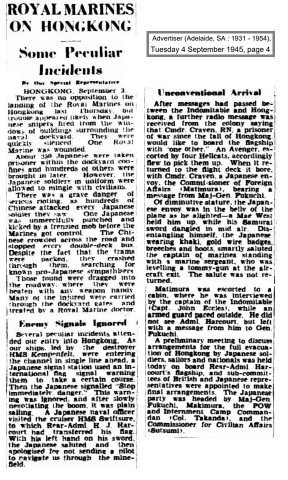

| ROYAL MARINES ON HONGKONG -Some Peculiar Incidents 30.8.1945 |

|

After messages had passed between the Indomitable and Hongkong, a further radio message was received from the colony saying that Cmdr. Craven, RN, a prisoner of war since the fall of Hongkong, would like to board the flagship with "one other." An Avenger, escorted by four Hellcats, accordingly flew to pick them up. When it returned to the flight deck it bore, with Cmdr. Craven, a Japanese envoy, the Commissioner of Foreign Affairs (Matimura), bearing a message from Maj-Gen. Fukuchi. Of diminutive stature, the Japanese envoy was in the belly of the plane as he alighted—a Mae West held him up, while his Samurai sword dangled in mid air. Disentangling himself, the Japanese, wearing khaki, gold wire badges, breeches and boots, smartly saluted the captain of marines standing with a marine sergeant, who was levelling a tommy-gun at the aircraft exit. The salute was not returned. Matimura was escorted to a cabin, where he was interviewed by the captain of the Indomitable (Capt. John Eccles), while an armed guard paced outside. He did not see Adm. Harcourt, but left with a message from him to Gen. Fukuchi. |

Comments

Keiji Makimura's memories of the Japanese surrender

Keiji Makimura's memories of the Japanese surrender - Excerpts from the Japanese content

Source : ダイヤモンド, 第 40 卷 (Diamond : economic journal 40 , 1952) - '香港降伏使 -牧村慶治 '

(https://jpsearch.go.jp/item/dignl-10294795)

Thanks Alan, it is good to…

Thanks Alan, it is good to get a Japanese viewpoint of the events. If you are posting Japanese text, it would be great if you could also include a note with an English summary. Here is a translation from ChatGPT 3.5. (This is the first time I have used it for translation. I find the text sounds more natural than we get from Google Translate, but ChatGPT has a reputation for occasionally adding in random information that sounds believable but isn't accurate, so treat with care!)

The story told by the British and Japanese sides

Keiji Makimura's memories of the Japanese surrender (Part two)

(I use AI tools to translate Japanese content : https://gwulo.com/media/51693)

Keiji MAKIMURA (aka 牧村慶治) :