This is the second of my recent purchases. It's only a small image, roughly 2 inches by 2 inches, but when I used my magnifying glass I could see it showed something I've written about, but hadn't yet seen a photo of.

What: Here's a closer look so you can see what caught my interest.

The man has put dried grass under the sampan's hull and set it alight. This is a process known as breaming, and used to be a regular task for anyone who owned a boat with a wooden hull.

Over time, barnacles and seaweed build up on a boat's hull, making it slower in the water. Breaming burns that away, restoring the boat's performance - think of it like taking a car in for a regular service to keep it running smoothly. Of course, lighting a fire next to a wooden hull can go very wrong, so the person doing the breaming has to pay close attention!

To get access to the hull, the boat needs to be beached, and leaned over onto one side. This is known as careening.

Careening wasn't just used for breaming, and it wasn't limited to small boats like the one in this photo. e.g. in the days when the Royal Navy's ships were made of wood, if the crew needed to work on some part of the ship that was usually under water, but they were somewhere that didn't have a dry dock, they'd have to careen the ship.

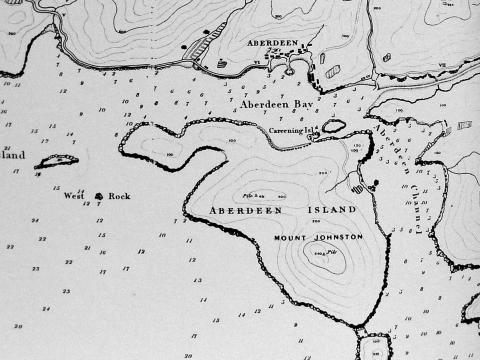

In the extract of Collinson's 1845 map shown below, you'll see that in Aberdeen Harbour (shown as Aberdeen Bay on the map) just north of Ap Lei Chau (Aberdeen Island), a small island is labelled as Careening Isld. This was important information for early visitors to Hong Kong, as Hong Kong wouldn't get its first dry dock until the end of the 1850s.

Who: The man in the photo is probably just the owner of the sampan, as it isn't large enough to need any specialised equipment or manpower to handle the job.

Where: There aren't any notes on the photo, or distinctive landmarks in the scene. So I can't guarantee this photo was taken in Hong Kong, though that is what the seller said. They may have taken the photo from an album of Hong Kong photos, which would have given them its location.

When: Again, I don't see any obvious clues in the photo, and we can't see the clues we'd get if we had the full album. If you spot anything, please let us know in the comments below.

Gwulo Photo ID: ET002

Further reading:

I read an interesting article, Copper-Bottoming the Royal Navy, while learning about careening and breaming. It explains that the Royal Navy was the first to cover their ships' hulls in copper sheeting. The copper reacts with seawater to produce a chemical film that is toxic to weed, keeping the hulls clean, making the ships faster, and avoiding the need for careening. Even more importantly, the copper kept shipworms at bay - those worms would feast on unprotected wood, and could cause major damage to a ship's hull. Copper-bottoming thus gave the Royal Navy important advantages over their rivals. You can read the article at the U.S. Naval Institute's website.

Closer to home, this photo has several links to photos in Volume 3 of my books:

- Photo 5 at Staunton Creek shows what looks like a drying rack for grass that would be used for breaming

- Photo 10 mentions the arms race between the world's navies

- Photos 13 and 14 show some of Hong Kong's dry docks, a much better solution than careening

Comments

Re: Careening Isld

Hi There,

Based on the location of the map, I believe we can visit the mentioned Careening Isld nowadays, on land. It is just next to the Hung Sing Temple in Ap Lei Chau. It is fenced up and may be an offence to climb up the rocks if you are not in official business there though.

T

Careening, etc

The first mention of Aberdeen's careening beaches in western sources was John Kendrick's report in 1794 that subsequently reappeared, first in Alexander Dalrymple's nautical instructions for the route to Canton, and then in Horsburgh's India Directory (what happened next is an interesting story for another time). In local argot the small islands that sheltered the beach from the swell that rolled into Po Chong Wan (until the typhoon shelter wall was built) was Duck Egg Islets (Ap Dan - not sure about which term was used for islet, probably Chau). Much of the careening space was swallowed up in the 1920s reclamation and all of it went with the construction of the first road bridge in the 1970s.

The ship equivalent would have had a strong point ashore (for the three careening capstans at Nelson's Dockyard in Antigua, see https://msummerfieldimages.com/nelsons-dockyard-english-harbour-antigua…) - where there was no dockyard infrastructure, ship's anchors were carried out and buried. Ropes and tackles were then taken from strong point to the mast hounds (top of a mast's LOWER and thus strongest and best supported mast element) and the ship was then 'hauled down' to expose the lower hull for scraping (to get the big stuff off) and then breaming (to kill the greeblies).

Small craft like this sampan could be careened and breamed more often, so scrapers probably weren't needed. There wasn't enough heavy growth to require it.

In fairness to our forebears, and certainly where small craft were concerned, careening was an excellent solution to the problem and far, far more cost-effective. A careening beach could accommodate several vessels at once, unlike a dry dock. It was also less vulnerable to the sort of problems that arose settling a ship on the keel blocks, getting the shores in place and then pumping dry (see, for example, https://www.maritimejournal.com/industry-news/research-ship-topples-ove…), or the problems of making sure, as the dock was refilled, that the ship refloated all at once, thus not risking breaking its back.

A middle ground between a careening beach and a dry dock is a scrubbing grid (https://www.wandersailing.com/blog/2019/9/4/tidal-grid), though for both that and a careening beach Hong Kong's tidal range, at c.2m, is a bit tight since the time interval between a boat drying right out and the water beginning to cover things is short. I can't remember ever reading of a scrubbbing grid in Hong Kong, though I know the Aberdeen Boat Club once thought of creating one on the tombolo between Ap Lei Chau and (to give the islet its correct name) Ap Lei Tsai, because I was tasked with doing the detailed survey soundings (November 1974).

Much the most interesting element in this photo is how the sampan owner achieved the equivalent of hauling down. It looks like the owner made a careening frame, with a cross-piece lashed from gunwale to gunwale, and on the side that was to dry out upwards, with a canted pole lashed to the outer end of the crosspiece (it's a very simple single part square lashing), and angled out to a firm bit of ground, so that as the tide went out and the sampan settled on the beach, it ended up starboard side up (in this case). Same principle as a full-keel yacht's drying legs, though those are intended to keep the yacht straight and level. At the change of tide, the owner would presumably switch the pole to the port side end of the crosspiece and repeat the operation. It's pretty effective, but set up like it is, it doesn't roll the sampan far enough over to give the breamer full access to the bit of the hull midships between the keel and the turn of the bilge.

Great stuff. Thanks David.

StephenD

Careening Isld.

A painting of Careening Island in 1923 can be viewed here.

Ap Lei Chau Careening Island and Eggs

"Place" pages for the Careening Island, being the West Egg, and the East Egg are at https://www.gwulo.com/node/29771 and https://www.gwulo.com/node/29772 .

Painting

Good find Klaus. Dumb of me - I should have remembered that painting. I wrote the caption! The 1920s reclamation, which is in progress, was a good dating indicator.

stephenD

We had several converted…

We had several converted sampans and then junks in the 60s and 70s moored at Sai Kung. They were careened at least yearly, except for the larger junks that went up on the slip way.

The sampans and the smaller junks were stripped and sunk when a typhoon was going to pass oven Hong Kong and then sunk to their gunnels on their moorings. All survived intact!

I’ll try to find a photo, most amusing.

Ciao Christopher Millington

Peng Chau

James Hayes wrote an interesting RASHKB journal entry on Peng Chau that features the fees and politics of breaming, the whole document is interesting, but page 17 pays special attention to breaming. This fellow here seems to be in a fairly crowded location, perhaps he would also have to purchase the grass?

Chinman

breaming

In fairness James' piece (indeed fascinating) mentions only one charge (20 cents per boat), describes it as a 'squeeze' by the resident military and, in any case, is writing of the period before 1899. Unquantified charges are mentioned where a careening beach gave access to ancestral graves and, no doubt via some local landholding system, gave the relevant family rights over the beach.

He makes it clear that back then the person doing the breaming did pay for the grass, but qualifies that by noting it was a choice, since space aboard was scarce and suitable dried grass is bulky.

How much any of that translated to the mid-20th century is moot, though I'd suppose that the broad heads - possible beach use costs, payment for breaming grass, scarcity and remoteness of beaches that were free of access and use, would have continued.

On sinking vessels to handle incoming storms. This is quite an old (and as far as I know nearly universal) practice, and one I've used myself riding out strong weather at anchor and sinking the dinghy, either on its own anchor nearby, or on a line tethered to our transom.

Stephen D