Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke - as he became after changing his birth name by deed poll - arrived in Hong Kong as Medical Director in 1938. After the Japanese victory he was not sent to Stanley but allowed to continue his work for the benefit of all communities. As well as his official duties, he organised the purchase of drugs, supplementary foodstuffs, and medical equipment, and arranged for these items to be smuggled into Stanley, Shamshuipo and other camps and hospitals.

He was arrested at the St. Paul’s (‘the French’) Hospital, where he'd been interned for most of the war, on May 2, 1943, on suspicion of being the head of the British spy organisation in Hong Kong (in fact his activities, although regarded as illegal by the Japanese, were purely humanitarian). He was brutally questioned at the Supreme Court Building for 10 months but revealed nothing. He was moved to Stanley Prison under sentence of death, but was reprieved, and in December, 1944 released to join his wife (Hilda) and daughter (Mary) at Ma Tau-wai Camp in Kowloon.

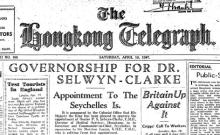

He resumed work as Hong Kong’s M. O. in July 1946. He became a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) in 1945 and a Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE) in 1951. In the spring of 1947 he was appointed Governor of the Seychelles.

Comments

“His Majesty the King has

“His Majesty the King has been pleased to confirm the provisional appointment of the Hon. Dr. Percy Selwyn-Clarke, M.S., M.D., B.S., F.R.C.P., M.R.C.S., D.P.H., D.T.M., Barrister-at-Law, to be a Member of the Executive Council of Hongkong in the absence of Mr. Richard McNeil Henderson, M. Inst. C.E., M.I. Mech E., with effect from April 6, 1939.”

Source: Hong Kong Daily Press, page 8, 12th June 1939

Selwyn-Clarke under the Kempeitai

This SCMP piece gives a stirring account of Dr Selwyn-Clarke's bravery during the war, together with a photo of him in later life.

Kreol Magazine Piece with Photo

Kreol Magazine has this piece on Dr Selwyn-Clarke together with a picture of him in his Governor's regalia.

Unannounced visit to Fanling Babies' Home

Dr Clarke (sic) gets a mention in Jill Doggett's book on the occasion when he paid an unannounced visit to the Fanling Home just before the war (1941?), accompanied by 'the ever-cheerful Dr Lam'. They were struck by the pervading peace and quiet in the home, considering there were 60 babies and 16 members of staff.

Mildred Dibden was caught by surprise at this visit by the Hong Kong Director of Medical Services. Her first thought was alarm that she had contravened a regulation, but she needn't have worried. As he took a walk through the different nurseries, the Doctor commented on the quietness. He wasn't to know that it was actually the 'quiet time' of day and the toddlers were all bathed and fed and lying in their cots. It was also 'clean linen' day. It was the perfect time to visit!

And he was there to help. Asking Mildred whence she obtained her medical supplies (Watson's the chemist) he suggested that she might now source her requirements from Government Medical Stores. 'Just send your list to Dr Lam at Taipo.' And then he was gone.

Shortly after, Dr Lam brought in a large package of chocolate for the babies, 'the first of many kindnesses to come.'

Selwyn-Clarke: a little more. . .

Just filling out the picture of this extra-ordinary man without too much unnecessary repetition of what’s been said already. If there were ever a Hong Kong Hall of Fame, he would get my vote for it.

Born in 1893 Selwyn Clarke trained at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London University and served in WW1 as brigade Medical Officer. He was promoted to captain and awarded the MC. After demobilisation he began a long and distinguished career in the colonial medical service.

In 1935 he married Hilda Browning, and they had one daughter. His wife, known as ‘Red Hilda’, was an ardent left-winger with political ambitions, and she played an important part in his history. When the War came she refused to be evacuated and stayed to support her husband in all he was doing to help sustain medical services after the Japanese invasion, part of which was to acquire quantities of special food and drugs which he foresaw would be essential for the treatment of the deficiency diseases which would soon appear in the colony.

When Dr Clarke was arrested for spying by the Kempeitai in 1943, he endured two years of imprisonment which included solitary confinement, beatings and torture, which left him bent and disabled but unbowed, (He carried a physical disability until his death), and his mental powers and resolution remained undimmed.

After the War ended, he insisted on setting up the medical services again in Hong Kong before going on leave, returning in 1946 to continue as Hong Kong’s MO. He was knighted and made Governor of the Seychelles in 1947.

He wrote down his memoirs, Footprints, and dedicated them to a Japanese interpreter, a Christian minister of religion in civil life in Japan, who had risked his own life to help many in Hong Kong who were victims of the war, even though they were officially enemies of his own country.

‘He was - and remained - a good physician. He was a meticulous and tireless administrator; he was also single-minded, and favoured his own ideas and plans.... He argued in their support politely, but strongly and persistently. He was a very brave man; few could have approached the level of courage with which he endured imprisonment.’

Source: This piece from the Royal College of Physicians website.

Beth Nance on Selwyn-Clarke

American missionary Beth Nance in her autobiography has a word of appreciation for Dr Selwyn-Clarke and what he did for internees in Stanley Camp (where she was) during the war.

After Hong Kong fell, and he was permitted to continue in his role as Chief Medical Officer, he 'ably interceded with the Japanese on behalf of the prisoners for their special medical and dietary needs. From time to time he reminded them of the Geneva Convention and what they were supposed be doing. He set up a diet kitchen so that this food got special attention, which made it more edible for those who couldn't cope with the coarseness. Some people lived longer because of it.... some people survived because of it.'

Chronology of Selwyn-Clarke's time in prison

I have been trying to construct a more precise chronology of Dr. Selwyn-Clarke's time in prison as he understandably only gives 'order of magnitude' estimates in his autobiography. In the process I also learnt about another 'movement' of the Bedales Bible.

The chronology is given below. Selwyn-Clarke gives the first and last dates in his autobiography, and I've been able to establish one more date precisely and rough time periods for two more.

Timeline

The first date is known from multiple sources:

May 2, 1943 Selwyn-Clarke is arrested at French Hospital and taken to a cell beneath the former Supreme Court. He is now in the hands of the dreaded Gendarmes (aka the Kempeitai).

He tells us in his autobiography that after the first set of 'treatments', during which he admitted nothing, he was given 'something that passed for a trial, though it was merely a sentence of execution'.

An approximate date for this trial can be calculated from testimony of the Jesuit Father Patrick Joy, who records that he was taken from the Supreme Court to Stanley Prison with Selwyn-Clarke and others on June 13, 1943:

June 13, 1943 First Trial took place sometime, probably quite soon, after this date

But Selwyn-Clarke responded to the death sentence with, 'The sooner the better. I'm extremely tired of your methods of investigation' and this defiance was punished with further 'investigations' although the death sentence remained. My reason for suggesting that the trial followed swiftly after his move to the prison is that he doesn't mention leaving the Supreme Court at this point in his memoir, which makes me think that these events concluded in his being sent back to the Supreme Court within a short time frame.

But when did he leave the Supreme Court cells for good?

Selwyn-Clarke tells us that he was moved from the Supreme Court to Stanley Prison after 'about ten months' from his arrest. We can give a date before which this must have happened.

On April 3, 1944 Franklin Gimson, the British leader in Stanley, was disturbed to discover that Hilda Selwyn-Clarke had received some of her husband's clothes as well as the Bible she had sent him previously. The next day he learnt from the Camp authorities that Sewlyn and the other British prisoners had been sent for further investigations preliminary to a trial and they could only take a certain number of possessions into their new form of custody. Hilda asked Gimson to try to get the Bible sent back to him as she knew how much it had meant to him.

This means the move was probably between 10 and 11 months after his arrest, close to Selwyn-Clarke's own estimate:

Late March-April 3, 1944 about this time Selwyn-Clarke was sent from the Supreme Court to Stanley Prison.

Although 'further investigations' sounds ominous, in most (but not all) cases brutal interrogations stopped when the prisoner left the custody of the Gendarmes for that of the prison service. Another prisoner, the banker Hugo Foy, was questioned 'about April' by the prosecutor Major Kogi but his account makes it sound like this was fine-tuning of evidence ready for the trial rather than an attempt to get new information. Foy believes that the reason there were no more than two death sentences at this trial was that Kogi was replaced by a better educated man who had spent some years in Europe and did not ask for capital punishment in most cases.

We know from multiple sources when this trial took place:

August 29, 1944 Second Trial alongside 38 other men and one woman. Selwyn-Clarke gets three years (not including time served)

Selwyn-Clarke tells us that his second trial was about sixteenth months after the first, so this ties in roughly with a date in the second half of June for the first trial.

We know when his ordeal came to an end:

December 8, 1944 Selwyn-Clarke and other prisoners were released as part of an amnesty to mark the third anniversary of the beginning of the Pacific War. He was sent to Ma-Tau-wai camp in Kowloon to be reunited with Hilda and their daughter Mary, who had been transferred from Stanley the previous day.

Ancestry Records Plus

The Selwyn-Clarke name seems to have been an issue from the start. He started off as Selwyn Percy Clarke. (His father was Percy). We may trace his evolving name as written in the different documents, mostly passenger lists. He did a lot of travelling, and it has not been possible to record all his trips.

1893 BORN 17 Dec, Stroud Green, London.

1901 Census, at Rookwood, Friern Barnett, Percy Clarke 39, Head, Solicitor and Employer, and wife Alice Clarke 39, then six children, aged 1-10 of which Selwyn Percy Clarke 7 was third in line. There were two servants, Ethel Maud Johnson 24, Nurse Domestic, and Annie Blessett 19, General Domestic.

SCHOOLING…

1911 Census – Selwyn Percy Clarke, 17, scholar, Bedales School, Co-Educational Proprietary Boarding School, Bedales, Petersfield, Hants.

CAREER…

1912-16 St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School

1916 MRCS, LRCP

1918 Military Cross after serving as Medical Officer in France, WWI, wounded twice.

1919 Bachelor of Science

THE COLONIAL SERVICE - Posted to WEST AFRICA…

1920 30th December, passenger arriving London from Accra, W Africa, on the Appam, Percy S Clarke, 28, medical, St Bart's Hospital, London EC1, Country of res: England.

1921 MD London

DPH (Cantab)

1923 15th Sept arriving Liverpool from West Africa, on the Appam, Dr Percy Selwyn Clarke-Selwyn, (sic!) 29, medical, proposed address Updene/Lipdene, Finchley Road, Hampstead, NW3. Country of res: Gold Coast.

During this time Dr S-C authored articles on Smallpox in the Negro Population British West Africa, Fever in Gold Coast Colony, Plague in Kumasi etc.

Medical Officer Barnwell Military Hospital. (date n/k)

Res Med Officer Royal Victoria Hospital Dover.(date n/k)

1924 Electoral register, 118 Streatham, Hampstead. Percy Selwyn-Clarke.

1926 MRCP

1928 26th Sept Arriving Southampton from New York (residence), on the Berengaria, Percy Selwyn-Clarke 35, doctor, residence: foreign country, destination: Royal Societies Club London.

1928 6th December, arriving London from Naples, Dr P S Selwyn-Clarke, 35, doctor, destination: Royal Societies Club, SW1, Permanent Residence: England.

1935 25th Oct, Departing Southampton for Cape Town, S Africa, on the Winchester Castle, Dr P S Selwyn Clarke 41 and Mrs Selwyn Clarke 36, from St Ermin’s (Hotel?) Westminster, London, perm res England. Medical.

1935 23rd Dec Arriving Southampton from Cape Town, on the Armadale Castle, Percy Selwyn-Clarke 41, doctor of Medicine, also Hilda Selwyn-Clarke 36, Housewife, destination: St Ermin’s (Hotel?) Westminster, London, perm residence England.

1937 FRCP

1937-43 DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL SERVICES HONG KONG.

1941 The Japanese invade. He is permitted to continue as Director of Medical Services.

1943 May - 19 months of solitary confinement and torture.

POST-WAR REPATRIATION…

1945 Oct 28th The Chitral repatriation ship arriving Southampton from Hong Kong (Only 1 day later than those on the Empress of Australia) Hilda Selwyn-Clarke 46 and Mary 9. Destination: Hither Northfield, Steep, Petersfield, Hants.

(Dr S-C stayed in Hong Kong to reorganise the medical services and arrived one month later. See next entry)

1945 20th Nov, on the Empire Lagan (Ministry Of War Transport), arrived Liverpool from HK, Dr P S Selwyn-Clarke 52, no destination address, Director Medical Services HK.

1945 CMG Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George is the sixth most senior in the British honours system and recognizes individuals who have made significant contributions to the UK, Commonwealth or its international relations.

After just 7 months recovering back in England, HE RETURNS TO HK…

1946 25th June departing Liverpool for HK, Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke 52, last address 35 Dover St, London W1, intended permanent residence Hong Kong, Director of Medical Services.

1947-51 GOVERNOR OF THE SEYCHELLES.

1951 KBE The second highest rank in the Order of the British Empire. [The highest rank is Knight or Dame Grand Cross (GBE)]

1951-56 Ministry of Health

1956 Retirement

1976 Died 13 March, aged 82, Hampstead, London. (England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index).

Thanks for this Aldi. If my…

Thanks for this Aldi.

If my memory is correct, I took the name 'Selbourne' from the notice of his name change by deed poll. I am now unable to locate this on the internet, but note that the Dictionary of National Biography also gives this as his original middle name.

I'll see if I can order a copy of his actual birth certificate, which should settle the matter.

I've found the link to…

I've found the link to Selwyn-Clarke's name change:

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/31406/supplement/7751

He was indeed 'registered' as Percy Selbourne Clarke but 'from infancy known as Percy Selwyn-Clarke'.