Hi all,

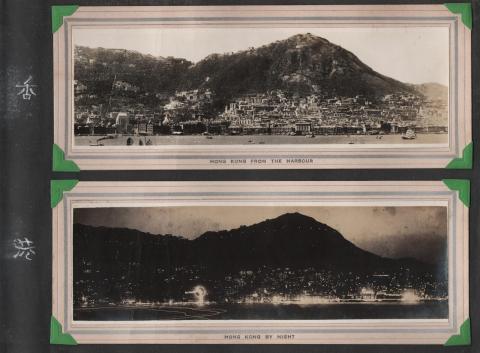

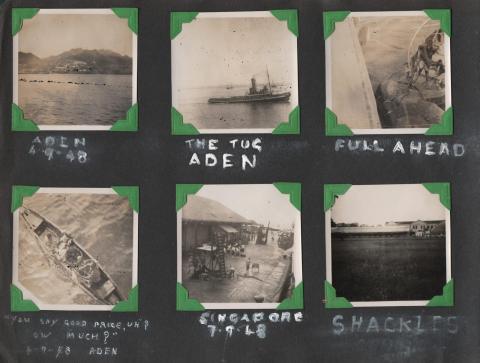

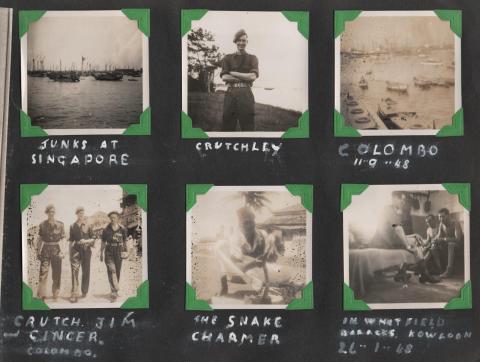

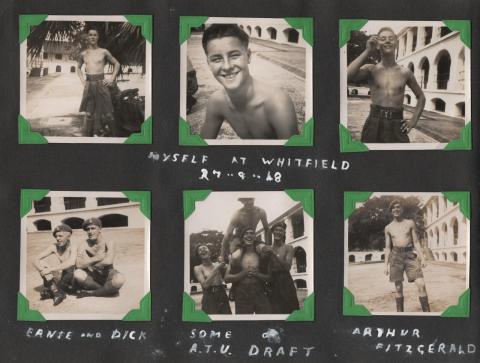

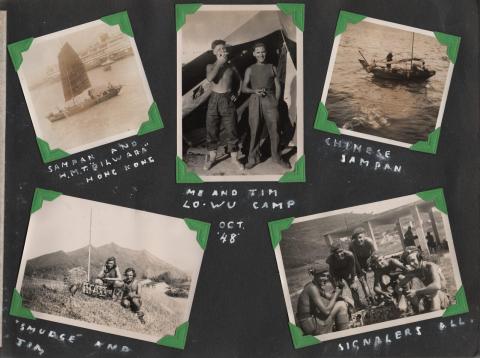

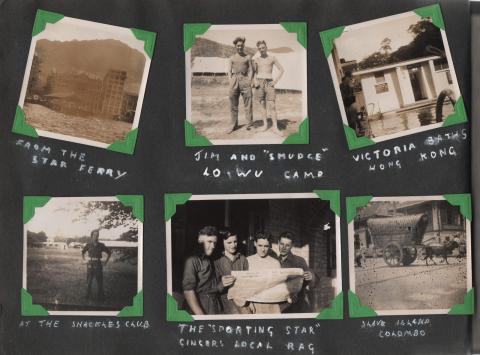

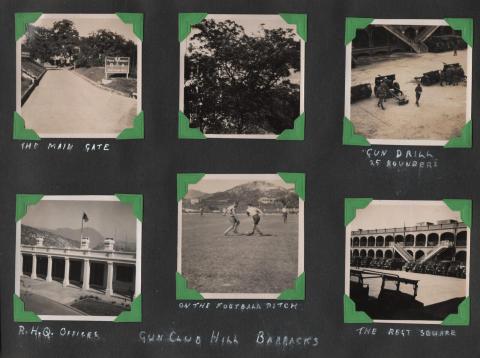

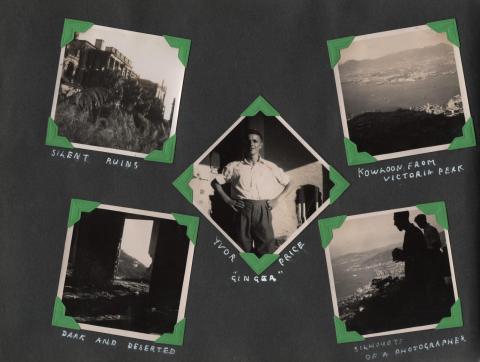

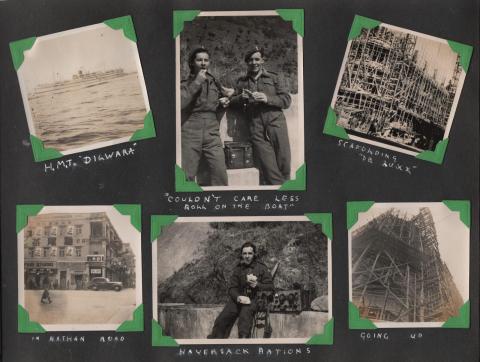

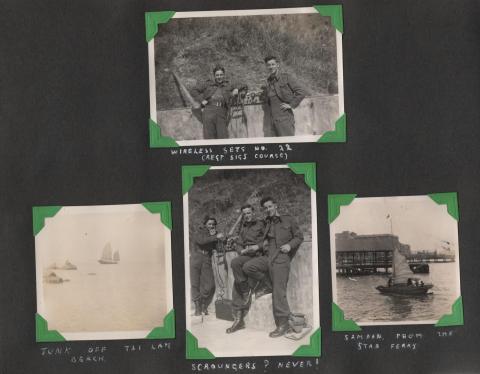

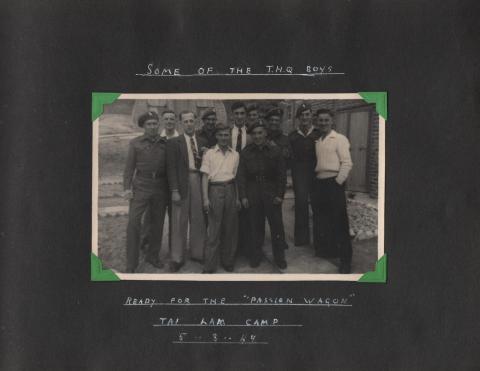

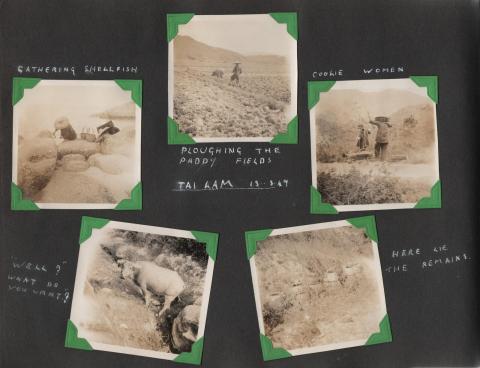

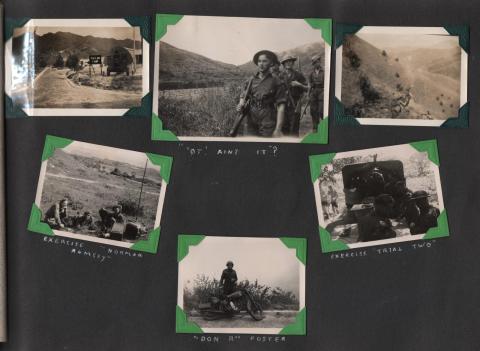

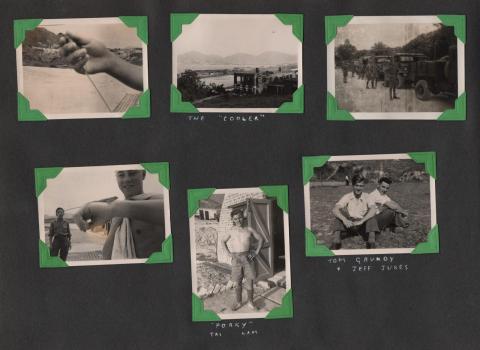

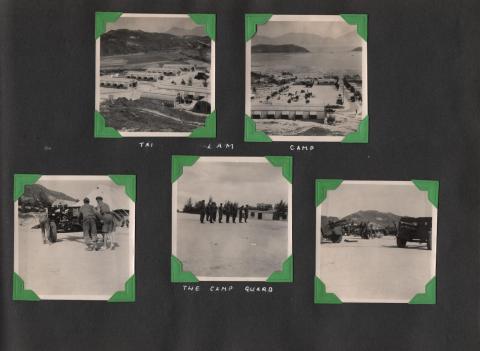

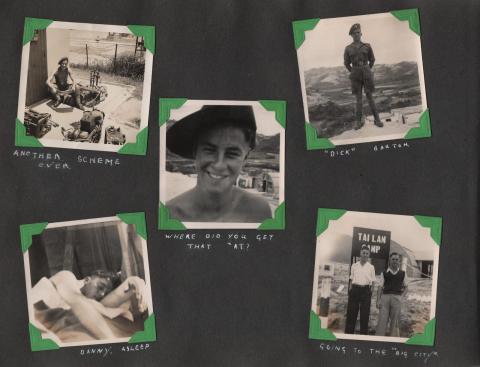

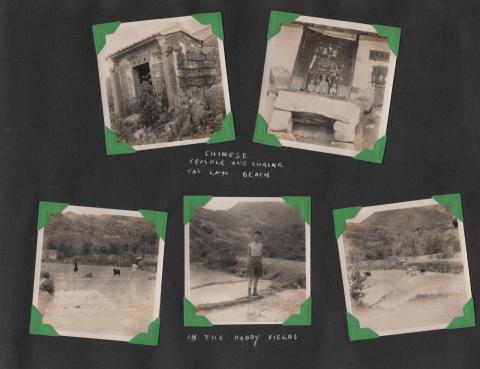

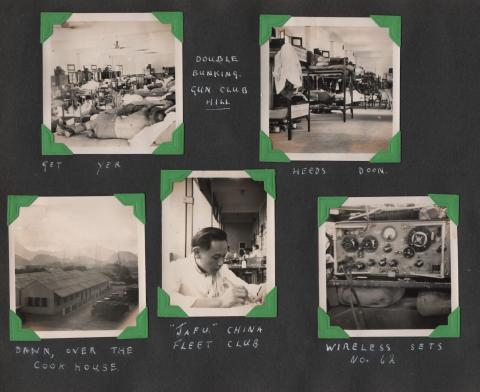

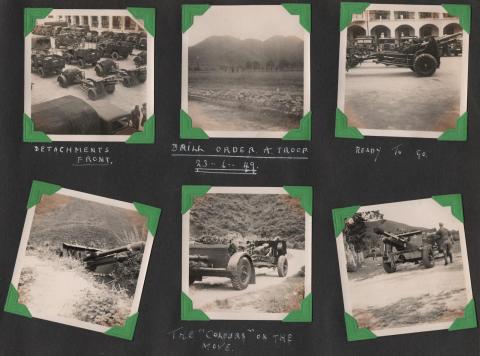

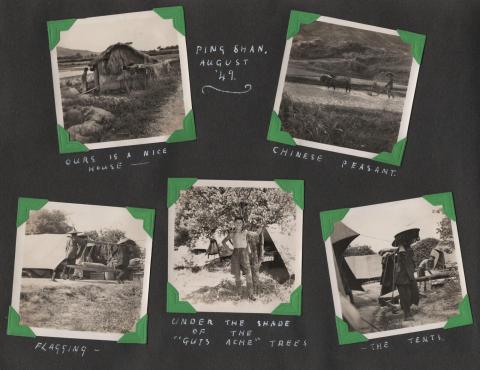

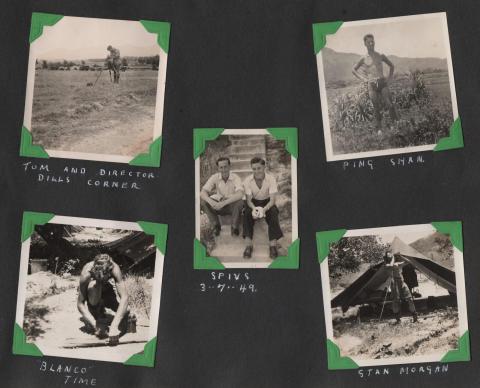

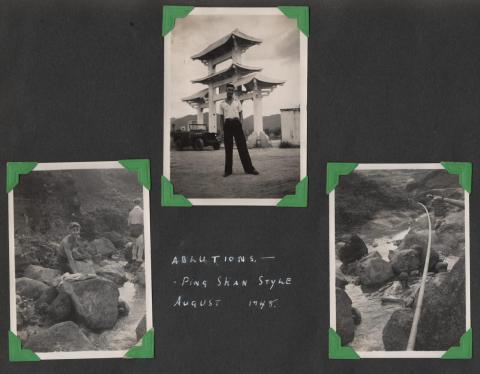

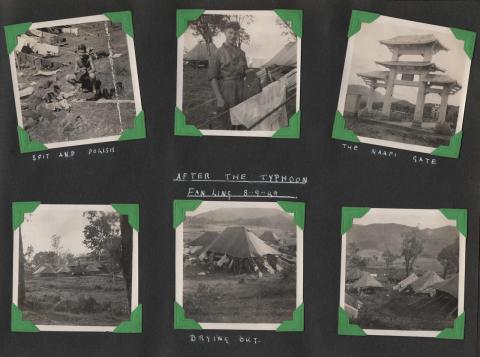

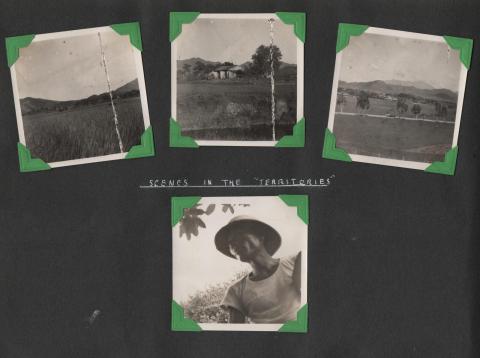

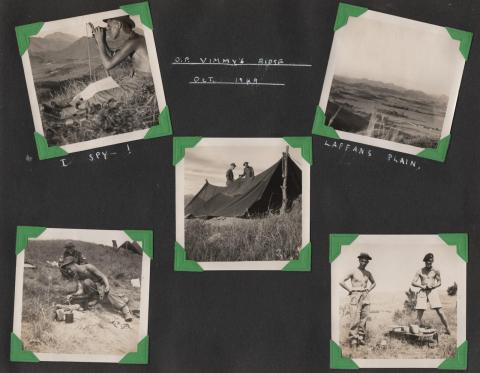

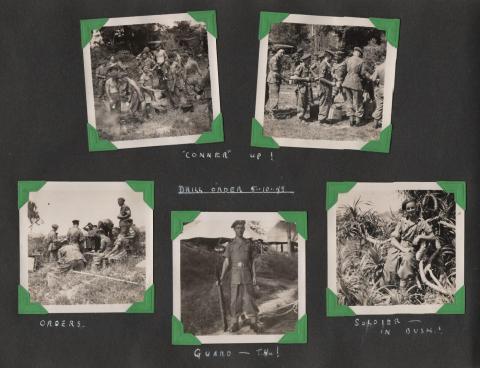

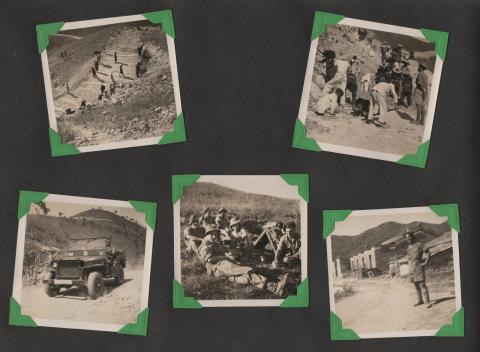

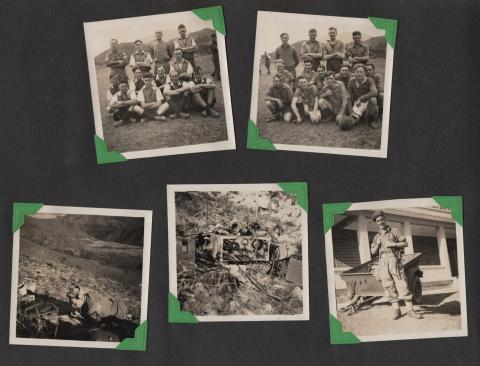

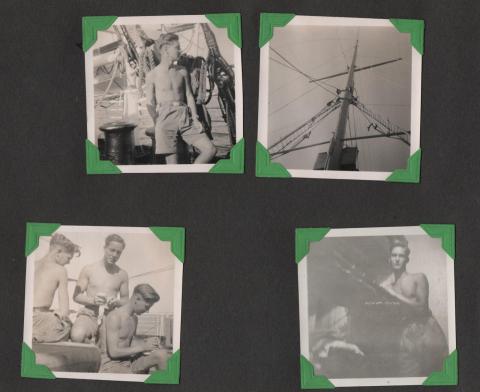

My grandfather did his military service in Hong Kong, 1948-49, and although sadly he was not able to return to visit before he passed, he always told us stories of the place and his times here.

I inherrited his photo album of these two years, and have uploaded the photos below. These are scans of each page, if people are interested I can upload higher resolution scans of each individual photo.

I only realized recently that the photos of drills in October 1949 would have been the British army preparing for potential invasion by the PLA. He was stationed on the hills overlooking the border in mid October when the KMT withdrew and the Communist army took their place over the border.

re: NRP Military Service 1948-49

Thanks very much for sharing your grandfather's photos with us. If you're able to add higher-resolution scans of the individual photos, I'll enjoy seeing them.

Please could you also tell us about which unit he served in? Sometimes that will lead to comments and questions from families of other men who were here in the same unit.

@jj_hk

@jj_hk

I'm very glad indeed that you have uploaded these; in fact, after years of browsing this site, I've registered specifically to contact you. It looks to me as if your father was with 25 Field Regiment R.A. (likely 54-battery, but possibly HQ-battery). My grandfather, Fred Newman, was with this unit (54-bty) from 1948 to 1951 in Hong Kong and Malaya and would very likely have known your father. The names of many of the locations depicted in the photos--Tai Lam, Fanling, Whitfield & The Gun Club--are well-known to me, but you have provided the only images I have seen of many of them.

I have done a considerable amount of research in the unit and would be delighted to hear from you (especially to hear whether my suppositions are right).

You'll find a sample of what I've been doing here:

http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/family-soldiers-1-4th-essex-ww2-25…

Thank you for your comments!

Thank you for your comments! Actually it was my Grandfather, not my father, but very interesting to know your grandfather was in the same place at the same time!

At some point many years later he sat down to write his memoirs, this was 50 years later and some of the details may not be accurate, but he talks in quite some detail about his experience. I don't recall he mentioned which unit he was in, but he did mention various details that would probably be enough to identify it. I'll tidy it and post it, and hopefully you'll also find it interesting and perhaps useful in filling in some details in your research!

One snippet from his notes that caught my attention that I'd be particularly interested to know if you heard mentioned anywhere else:

I always wondered if this was true, or a just a tall story that got exaggerated over the years! There are some other stories in there, and mention of various names, hopefully it lines up with your research.

Give me some time, I will try and post the first section at the weekend. I'll also sit down and read the thread you shared properly, many thanks for sharing!

JJ

Thank you, and I'll post

Thank you, and I'll post higher resolution scans, I'll try and post some this weekend when I dig out his memoirs. Happy to see interest!

Apologies about the father

Apologies about the father/grandfather slip.

I look forward to reading what you can post from his memoirs.

I have the story of the deserter from a relative of the man himself and another member of the unit, though the location in China was Canton. His name was Gnr Raymond James Rose ('Tiger'), and he absconded with a friend from the Catering Corps.

Brief mention here:

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes…

I have the reason for their light punishment being that the city had just fallen to the Communists and they were able to give up-to-date information on the situation there.

Thanks again

CF

Interesting! My grandfather

Interesting! My grandfather mentioned that story several times, it's hard to imagine nowadays just wandering off into China, even if it was only up to Canton!

Before I post the first excerpt, I found a small mention elsewhere in his memoirs that you might find interesting:

I suspect the film is long lost, I wouldn't even know where to start looking, but I imagine it would be quite interesting viewing if it ever did turn up.

NRP Memoirs Excerpt 1: Voyage Out

First section of my Grandfather's memoirs from his time in Hong Kong, 1948-9.

I have skipped the early sections talking about basic training as they are less relevant to Hong Kong, but I'll start by posting his impressions of the journey out. I have lightly edited this for readibility, but mostly left things untouched. This includes parts that might be taken as offensive, or at least not "politically correct" as I believe it better to retain the flavours of the time than try to whitewash things later. No deliberate offense is intended to anyone, living or dead, by either the author or by myself.

I'm not sure when exactly he wrote this, but it would have been after 2000, so at least 50 years after the events described - I will leave it to readers to judge how much detail is accurately remembered. Note that my Grandfather was a keen birdwatcher throughout his life, so frequently notes and descriptions of birds pop up in his memoirs. I have left these intact for flavour, and because I suspect they're the most accurately remembered parts!

Thank you for going to the

Thank you for going to the trouble of typing it all up. 'We' aren't yet in Hong Kong, but you've already dropped one clue that helps me and confirms that your grandfather was with 25 Field Regiment, R.A.: he mentions Colonel Lamont. Puzzlingly, his name is omitted from the list of Commanding Officers in the semi-official listings, but I've found him mentioned by name in the paperwork for 40 Infantry Division in 1949: Lieutenant Colonel John David Alexander Lamont.

I've typed up a similar multi-page memoir from another member of the regiment (a national serviceman) for the same period. I'm not really able to upload it here as I do not have the authors permission and have since lost contact, but if you were to write to me, I'd be happy to email you a copy to compare with your grandfather's.

I look forward to future installments as and when you can find time.

CF

NRP Memoirs Excerpt 2: At Gun Club Hill

Happy it's of interest to you!

Fortunately the material is all typed up already, but I think he never returned to edit it, so it's a little disjointed. I've tried to keep the editing light but reorganized bits to give a structure - in most cases dates are not provided so I'm just grouping them around topic. I'd defintely be interested in the other serviceman's memoirs, I'll drop you a private message.

Here's another section:

More interesting material

More interesting material there.

You're correct that it was the 26 Gurkha Infantry Brigade.

The Buffs is 1 Buffs (The Royal East Kent Regiment), and they were soon joined by 2/6 Gurkha Rifles and 2/10 Gurkha Rifles.

What your grandfather describes (accurately) as troops arriving 'by the boatload' was the expansion of the post-war garrison to divisional strength (40 Infantry Division), which really got underway in July 1949 as Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War began to look assured.

Many thanks.

JJ,

JJ,

There could be a million and one things that have kept you busy (now more than ever), but just in case you may have thought there's a lack of interest at the other end, I can assure you I'm keen to read the next instalment!

Regards

Charley

NRP Memoirs Excerpt 3: Tai Lam and various 'schemes'

@Charley, yes, I've been caught up in other things, but I have the final two pieces here for you! Very happy that it's of interest!

This section gathers the "miscellanous" stories:

NRP Memoirs Excerpt 4: PLA Advance

... and this final section covers the communist advance:

25 Field Regiment RA

I have only just seen this 'thread' talking about 25 Field Regiment RA, and 54 Battery in particular, and it brought back immediate memories. The reason being is that I served in 25 Regiment, and as it so happens, I was in 54 Battery as well. I joined 25 Regt in 1968 and left when 25 Regt returned to the UK in 1971. 25 Regiment changed from a Field Regiment to a Light Regiment while training in the UK for our HK role. I stayed with the next Regiment out which was 47 Light Regt. Reading up on this old Regimental history definitely brought back memories.

@jj_hk

@jj_hk

It's a long-shot, but I've uploaded a few photographs here:

http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/family-soldiers-1-4th-essex-ww2-25…

And here:

http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/family-soldiers-1-4th-essex-ww2-25…

Please do let me know whether your grandfather features in any of them.

With Regards

CF