Of the many innovations in the twenty years after World War I, civil aviation was perhaps the most spectacular. Early aviators who broke records by flying to distant places were everywhere greeted by vast, excited crowds. A few years later, rich people could travel from city to city in North America and Europe in comfort and luxury beyond the imagination of ordinary people. New airlines were set up in many countries and some became giant corporations. Pan American Airways, usually known as Pan Am, became a world-wide cultural icon of the 20th century from its foundation in 1927 until its collapse in 1991. Its founder, Juan Trippe, was always looking for new horizons, and by the early 1930s had not only covered North America, but also commenced flights to Central and South America. The aptly named Trippe looked to commence trans-Atlantic flights, but was unable to overcome political obstacles. This meant that this route was out of the question for another two decades, so Trippe turned instead to look at the possibility of trans-Pacific flights. That seemed impossible as the distance from San Francisco to Hong Kong is 6,900 miles (11,100 km).

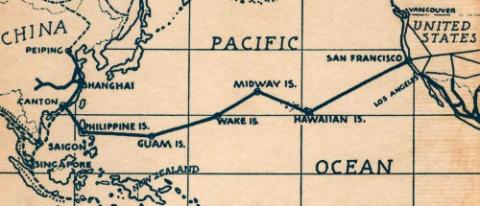

However, Trippe came up with an imaginative break-through. He hit on the idea of island-hopping using flying boats to cross the Pacific to the Philippine Islands, which from 1898 to 1946 were an American territory. The name ‘clipper’ was chosen for these fast new planes, referring to the sailing ships built in the mid-nineteenth century that were the finest and fastest sailing ships ever built.

The islands Trippe selected were American too: Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island and Guam. Wake Island was an imaginative choice, but it had problems. It was a tiny coral atoll, very remote, with a protected lagoon ideal for flying boats. Although uninhabited, it was infested by rats that had come ashore from 19th century ships that called there.

Little attention is paid to other details. The island shown as New Zealand is in fact New Guinea.

Much detailed work had to be undertaken to make these tiny spots on the vast Pacific Ocean fit to serve as bases for the big planes that would use them, including accommodation and catering on the ground for wealthy passengers who expected every luxury. Besides these were docking, repair, roads and radio facilities. Large quantities of aviation fuel had to be shipped to these remote locations and safely stored.

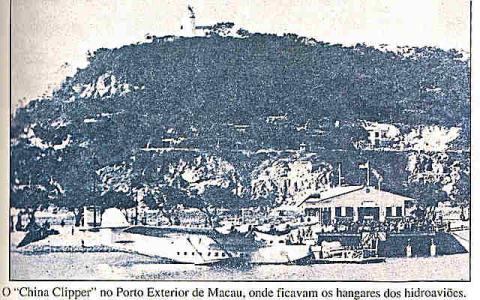

M-130 Clipper about to land in Macau.

At first, the route was operated with three Martin M-130 flying boats specially designed and built in 1935 by the Glenn L. Martin Company in Baltimore, Maryland. Their range was 2,500 miles (more than 4,000 km), enough for island-hopping, and far more than domestic flights They were ready for test flights by the end of the year. On 22 November an M-130, dubbed the China Clipper, took off from Alameda, California, in an attempt to deliver the first airmail cargo across the Pacific Ocean1. Although its inaugural flight plan called for the China Clipper to fly over the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (still under construction at the time), the veteran pilot, Ed Musick, realised on take-off that the large, lumbering plane would not clear the structure, and was forced to fly beneath the deck instead. On 29 November, the plane reached its destination, Manila, after traveling via Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island, and Guam. Over 110,000 pieces of mail were carried. It was a momentous achievement.

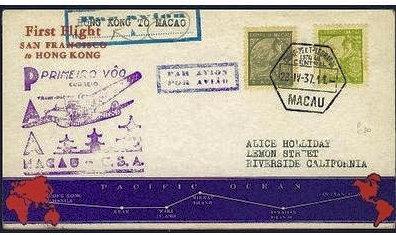

The M-130 carried a crew of nine and only eighteen night passengers, so it could never have operated at a profit. However, the inaugural flight’s success did serve to test the demand for the service. The two flying boats initiating the service in 1937 were named the ‘Hongkong Clipper’ (Manila-Hong Kong) and the ‘China Clipper’. The initial public response was encouraging. The Straits Times in Singapore reported on 28 April 1937:

‘The first transpacific flight by a commercial passenger airliner is completed when Pan American Airways’ Martin M-130, China Clipper, arrived at Hong Kong. The flight had departed San Francisco Bay, California, on 21 April with 7 revenue passengers and then proceeded across the Pacific Ocean by way of Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, Manila, Macau, and finally Hong Kong.’

The plane is a M-130 Clipper.

From the author’s collection.

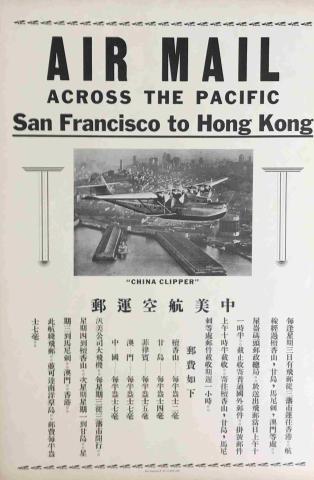

The poster is evidently intended for the large Chinese-American community in San Francisco. It reads in part:

|

An aeroplane will be sent to carry the parcels from San Francisco to Hong Kong every Wednesday. The route passes through Honolulu, Guam, Manila, and Macau, etc. The General Post Office at the Port of Oakland delivers airmails at 11:30 am on the day and no more mails for delivery on the day will be accepted after that time. The registered mail cut-off time is 10:30 am. The cut-off time for mails to Honolulu, Guam, Manila, etc. will be one hour later. Postage rates listed below: The flights of Pan American World Airways originate from San Francisco every Wednesday, landing in Honolulu on Thursday; landing in Guam next Monday landing in Manila, Macau and Hong Kong on Wednesday. Thanks to Mr Ng Man Kin, Assistant Curator of the Hong Kong Museum of History for the translation of the Chinese text. |

This first step encouraged Trippe to develop the plan much further. Pan Am commissioned from Boeing six huge new planes that could fly the long distances and carry a much greater load. Another six would be ordered later, but three of these were sold to the British Overseas Airways Corporation. The new Clipper 314 had a wing span of 46 metres, an empty weight of 21 tonnes and a loaded weight of 38 tonnes. Unlike the M-130, it had no external struts supporting the wings. The 314's first commercial flight to Hong Kong took off on 23 February 19392.

The advent of these giant clippers enabled the romantic era of trans-ocean flights to begin. Capable of comfortably flying 74 passengers and 10 crew for distances of up to 5,896 km, these luxurious aircraft captured the adventure seeker’s imagination. With names such as the Yankee Clipper and the China Clipper, they challenged ocean liners which took weeks to travel to places that the Pan Am Clippers could reach in a few days. These sleek, hulking seaplanes were the ultimate luxury – flying and floating five star hotels. The Clippers were divided into spacious cabins, with couches rather than aircraft seats. These passenger compartments would transform at night into deluxe sleeper cabins. There was a dining salon, dressing rooms, and separate bathrooms for men and women. Whilst today’s aircraft squeeze passengers into about six square feet, on a Pan Am Clipper, each passenger could luxuriate in twenty-two; six course dinners were served on fine china, and the only tickets sold were First Class3. These flying palaces were for the super-rich. A one-way ticket from San Francisco to Hong Kong via the ‘stepping-stone’ islands and Manila cost $US760 (equivalent to $14,000 in 2019).

Negotiating alighting rights in US controlled territory was relatively straight forward, but Hong Kong was another matter. Imperial Airways, established in Britain in 1924 as a commercial long-range airline to serve parts of Europe, planned to extend its routes throughout the British Empire, to South Africa, India and the Far East, including Malaya and Hong Kong. By the mid-1930s that lay well in the future, but the last thing Imperial Airways wanted was American competition. Therefore the Pan Am request for alighting rights in Hong Kong was refused.

Pan Am was not easily beaten. In 1935, negotiations took place instead with the government of Macau, which readily gave its consent4. The British government quickly reversed its decision, not wanting to appear to stand in the way of a major development in modern transport. Portugal would have gained much international prestige if it had sole rights for Pan Am’s flights to the China coast. Therefore, while the M-130 planes flew the route, Pan Am clippers flew to both Macau and Hong Kong, the flight between the two taking about twenty minutes. By contrast, the ferry voyage on the old Fatshan took several hours, often overnight. Eventually, Imperial Airways flew a demonstration flight round the world in June 1939, but the outbreak of World War II soon afterwards brought to an end any British plans for a commercial operation through Hong Kong.

On 8 December 1941, the Japanese attack on Hong Kong brought to an immediate end Pan Am’s Clipper encounter with East Asia. The story is graphically told by Greg Crouch in his book China’s Wings. His account comes from one of those caught up in what could have been a massacre had the Japanese attack taken place a few minutes later, with the crew and passengers aboard the Clipper, which was due to take off at 8.00 a.m. The story of the sudden Japanese attack early that morning is often told, but this is an eye-witness account from Chen Teh-tsan, usually known locally as T.T. Chen, a member of the Hong Kong ground staff of the China National Aviation Corp.

but no passenger terminal. As late as 1950, the terminal was little more than a shed.

“Pan Am’s S-42 Hong Kong Clipper floated on the placid waters of Kowloon Bay, tied against the flying boat pontoon. A few minutes before 8:00 a.m., Mr Chen was unloading the busload of Pan Am passengers he had escorted to Kai Tak from the Peninsula Hotel, the sumptuous lobby of which the airlines used in lieu of a passenger terminal. Suddenly, a noise. Everyone stopped. Airplane engines droned in the distance, growing louder. ‘Look!’ A passenger pointed to a gaggle of aircraft bearing down from the north at medium altitude. ‘They’re British’, someone dismissed. Chen had been in Chungking a few weeks before. He squinted at the formation. ‘No! Those planes are Japanese!’

Pandemonium erupted. The passengers scattered. At a run, four of them followed Chen across the street and leapt into a dry drainage culvert [a nullah] with a bunch of blue-overalled airport coolies. Maintenance Chief Soldinski sprinted to his car and raced for home. The crew of the Pan Am Clipper took shelter in the sturdy dock house and yelled for Captain Ralph, who was still in the plane.

The formation broke into parts and descended to attack altitude … With no RAF opposition aloft, the nimble pursuits peeled out of formation into line ahead and swooped to 50 feet, heading straight toward Pan Am’s flying boat like dragonflies skimming the surface of a pond.

Captain Ralph jumped through the Clipper’s door and sprinted down the dock. Bullets churned the water and chewed into the plane behind him. Too far to the dock house. Ralph flung himself over the side into three feet of water and splashed behind a concrete piling. One behind the other, six Japanese pursuits riddled the Clipper and screamed overhead to attack targets farther down the field. Bullets from the seventh ignited a fuel tank. The huge flying boat whooshed into flame. Heat seared the dock. Captain Ralph cringed behind the pillar, unharmed. The bombers cruised in level at 500 feet, their radial engine roar changing tone as they passed overhead. Black cylinders swished and fluttered earthward and boomed in rapid-fire succession among the parked airplanes. Hot shrapnel ripped bloated fuel tanks. Flaming geysers of aviation fuel gushed from torn fuselages. Massive secondary detonations annihilated the airplanes.

The attack ended as abruptly as it started. The Japanese droned into the distance and vanished about three minutes after they’d been sighted. In front of the hangar, the mangled remains of eight airplanes raged aflame under roiling palls of oily black smoke – three Curtiss Condors, the three Eurasia planes, and CNAC’s two DC-2s. Another greasy smudge jetted skyward from the ruins of the Pan Am clipper. The Royal Air Force’s contingent of pathetic biplanes – three Wildebeest torpedo bombers and two Walrus Amphibians – burned at the other end of the field.”

As Winston Churchill had commented in January that year, the defenders of Hong Kong stood ‘not the slightest chance’. Nor did the Pan Am Clipper, which burned to the waterline.

Stuart Braga

References:

- China Clipper, Wikipedia article, accessed 25 January 2019.

- Boeing 314 Clipper, Wikipedia article, accessed 26 January 2019.

- Luke Spencer, The Long Lost World of the Luxury Flying Boat, 15 December 2017.

- J.M. Braga was involved in these negotiations, and his file on this matter is in his papers at the National Library of Australia. He was the translator for the Pan Am team, and offered to take transit passengers going on to Hong Kong for a tour of Macau by car.

Comments

China Clipper by Stuart Braga

Amazing to read. Thank you very much Stuart. Is there a book on these trans Pacific flights? Their development through the 1930s. I flew SF-HK in 1979. Non-stop in 747SP. That was incredible!

Best wishes

John