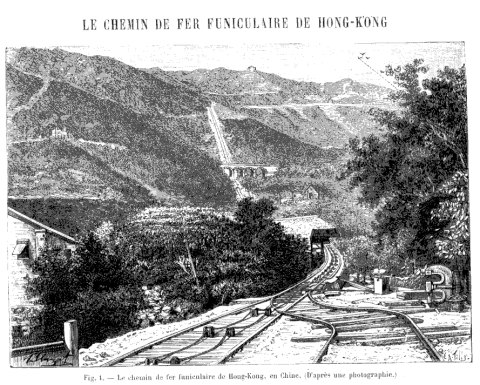

We have already noted in La Nature the principal types of special funicular or rack railways established in recent years on the flank of the mountains and which are of particular interest because of their steep gradients. The one whose view we represent in figure (fig. 1) which is installed in the island of Hong Kong which is, as we know, in front of the mouth of the Yangtze near Canton; it thus comes to us from China in a way, although it is established, in fact, on an island which has now become an English colony.

One of the oldest subscribers of La Nature, Mr. Huchet, passing through this island, was kind enough, with an arbitrariness for which we cannot thank him enough, to collect photographs and send us some information relating to this curious island which we believed would interest our readers and reproduce here.

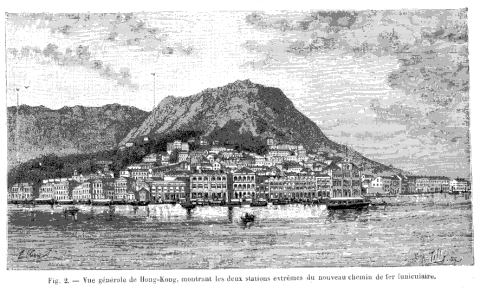

The island of Hong-Kong or Hiong-Kong, the island of Perfumed Waters, forms a steep massif of approximately 95 square kilometres in area, the soil of which is composed, says Elisée Reclus [French Geographer], of eruptive rocks, granite, shale and basalt. It was ceded by the Chinese to the English in 1841, and since that time it has become the obligatory transit point for all trade coming from Canton; it has also developed considerably. The capital city of Victoria or Kouantailon (??) which forms its main port, with its solid houses built of stone, its well-paved streets, of remarkable cleanliness, could stand comparison with the large European cities; and it would have in addition the marvellous natural scenery brought by the southern sun, in a country whose luxuriant flora includes, it seems, almost all the species of plants and trees found in the province of Canton.

However, the inhabitants, following the usual customs of the English, especially in southern countries, only stay in the city proper during the day, for their business, and they establish their homes outside the city, in cooler villas, built in the middle of the countryside, on the slope of the mountain overlooking the coast. There is thus established a continual coming and going, the inhabitants going to the neighbouring countryside every evening to find a little freshness, especially on hot days, and at the same time to escape the preoccupations of business and the noise of the city. Thanks to these habits and to this particular care for the comfort and well-being that the English are always concerned to find in their colonies, Hong Kong can be considered as the sanatorium of the Far East. The ascent to be made on foot is too tiring, and no other means of transport was known than the sedan chair, supported on the shoulders of two or four vigorous Chinese coolies; it is therefore to replace this somewhat primitive mode of locomotion that a company was recently formed in order to establish a railway connecting the summit of the mountain to the city, and, as the average gradient reaches 35 per cent, it was recommended that it was necessary to resort to a special type, such as the funicular railway. The railway rises there to an altitude of about 500 metres above the city, it has a total length of 1600 metres (fig. 1 and 2).

The route consists of two roughly straight lines, joined towards the middle by a bend, at a point where the line deviates to the left to reach the arrival station located in a small pass at the watershed. The terrain crossed is exclusively granite, which has allowed for great solidity in the infrastructure works despite the very steep slope of the track. This terrain is covered with agglomerated concrete in which the metal sleepers in the shape of an inverted “1” are anchored which support the rails. The only engineering works required for the construction of the line are limited to three viaducts, the largest of which is 50 meters long.

The Vignole-type steel rails [special type of tram rails] rest directly on the sleepers by their pads, they are firmly held by rail fasteners. The width of the track is 1.60 m. The line has only a single track until the middle of the route where it branches off into a double track over a length of 100 metres to ensure the crossing of the two interconnected wagons, one going up, the other going down, which provide the service. Above the crossing, the line continues as a double track to the arrival station, but with only three rails; the single middle rail serving as an inner rail on each of its lateral faces, thus replacing the two inner rails that two parallel tracks would require. This particularly economical arrangement is found an ingenious arrangement applied in such a case on the Giessbach funicular railway which we have previously described. In this remarkable installation the wheels of one of the cars have the flanges of their tires arranged on the inside of the track as on ordinary cars, and those of the other car have their flanges on the contrary carried over to the outside. On arrival at the crossing one of the external rails, that of the straight track, for example, continues without a break in continuity, and it forces the car with external flanges to deviate within, the corresponding rail being obviously interrupted opposite the deviation to let the hub of the matching wheel pass. The inner rail of the left track also continues on its side without interruption at the deviation, and as it is in contact towards the left with the inner flanges of the other car, it also forces the latter to deviate automatically. The cables used are made of steel wire resistant to 120 kilograms per square millimetre, they are composed of 6 turns of 6 wires, and can withstand a force of about 40,000 kilograms, with a diameter of 3 centimetres. These cables are at least two, they run parallel along the track, each passing over a series of special cast iron rollers arranged between the rails; but only one cable is actually used for traction, the other is only a safety cable having like this one its two ends attached to the cars, and it would engage to hold them if the traction cable itself were to break. According to the figures that Mr. Huchet was kind enough to communicate to us, the total weight of a loaded wagon would be approximately 10,000 kilograms, which would correspond for the cable to a force of 3000 to 4000 kilograms maximum to balance the component of gravity parallel to the track; this would be approximately 1/10 of the breaking load.

The driving force is provided by two compound type locomotives with a force of 40 horsepower each installed at the upper station. These machines are independent, they can each separately operate the traction winch formed by two pulleys each 2 meters in diameter on which the traction cable passes by making three turns. The drive resulting from the rotation of the pulleys determines the movement of the cable, which moves alternately in the two parts on each trip. As for the safety cable, it simply passes over a return bridge located at the top of the plane. The traction winch is also equipped with a special brake of instantaneous action for cases of accident. No special provision is indicated, however, for the brake of an automatic operation other than the safety cable to prevent the consequences of a breakage of the traction cable. The mechanic, installed on a platform situated above the winch, can monitor the entire track and he remains in permanent electrical communication with each of the two moving cars, doubtless by means of the cables themselves; but no special provision is indicated for the insulation of these conductors. The cars are formed of a solid chassis mounted parallel to the track, and resting on two articulated trucks as on American cars; they each have at each end a large platform capable of containing twenty-five passengers, with a first-class compartment in the middle.

Source: LA NATURE. No. 755. NOVEMBER 19, 1887 [a French Journal, digitized and online at the Conservatoire numérique des arts et métiers] Google translated from French