If I'm right, this pier is over 99 years old, and is an important part of Hong Kong's wartime history. See what you think ...

Background

After a recent outing to explore Lei Yue Mun, I remembered a mention of a pier in the area, that was used to evacuate troops during the fighting in 1941. I pulled out my copy of Tony Banham's Not the Slightest Chance, and found it in the entries for 12 Dec 1941:

02.00 A and B Company Punjabis leave the Sam Ka Tsun pier.

The area near Yau Tong with all the seafood restaurants is usually called Lei Yue Mun, but the name of the village there is Sam Ka Tsun, or 'Sam Ka Tsuen' on modern maps. The new maps also show a Sam Ka Tsuen Ferry Pier - but that pier is on a modern breakwater built long after 1941. Do any traces of the wartime pier remain?

I turned to the Hong Kong Historic Maps website to see what I could find out about the pier's location and history.

Sam Ka Tsuen in the 1890s / 1900s

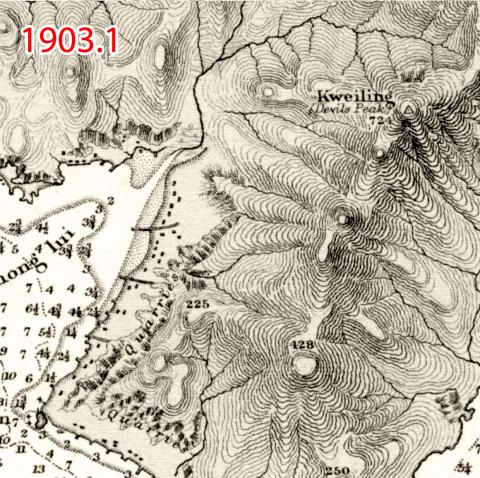

This first map is dated 1903. It shows the quarries where Hakka workers excavated granite for building from the cliffs in the area. There are small buildings along the coastline, and what look like small piers extending from the shoreline at several places, but no sign of any roads or a larger pier.

The map is actually a chart for sailors, and as we've seen before, they focus on giving an accurate record of the sea and shoreline, but their record of features on the land is often years out of date. The notes on the map say it came from surveys performed between 1886-1893, with 'Small corrections' in September and December 1903. So I believe the map above shows how the land looked in the early 1890s, when it was still under Chinese control.

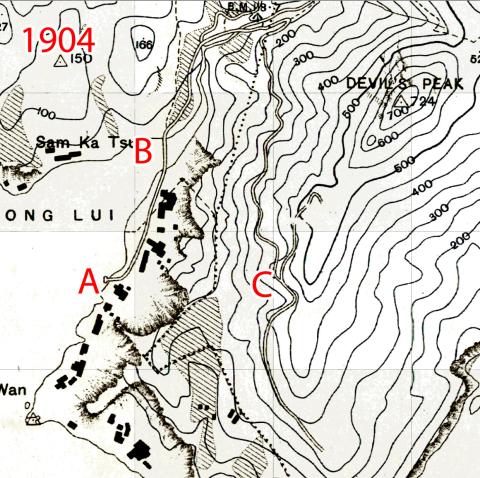

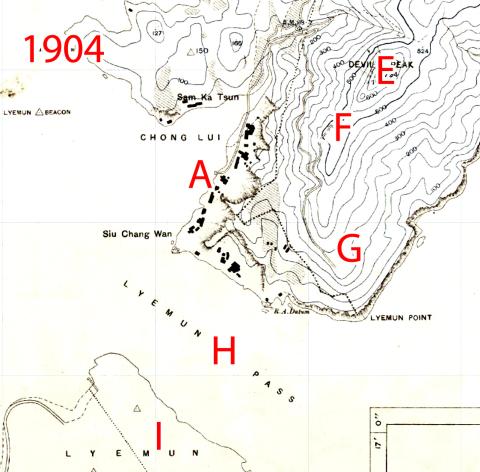

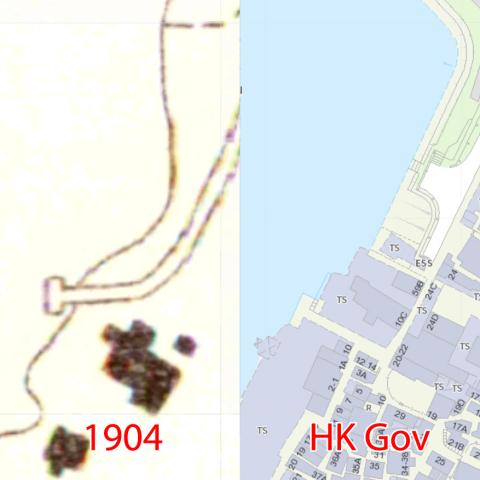

The next map shows how the land looked in 1904. This area was now under British control, part of the New Territories they'd leased in 1898. There's a new T-shaped pier that extended into the sea at (A) and a road that led north from the pier, across the water at (B), then uphill to where it splits at a fork (C) before apparently petering out on the hillside.

Why did the British rush to build a pier and a road so soon after leasing the New Territories, when the area was remote and lightly populated, and the road appears to go nowhere?

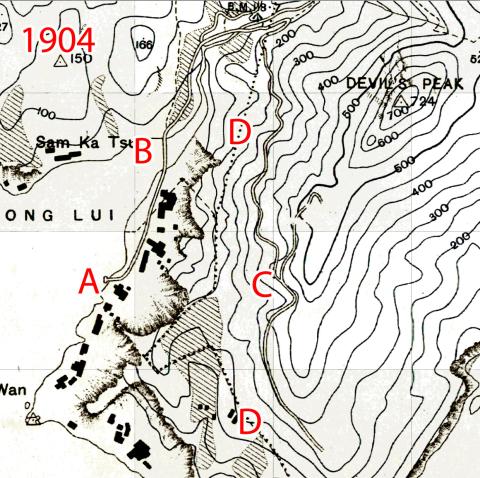

The clue is the dotted line (D) on the map.

The map key says that the dotted line shows "Boundaries of W. D. Land.", which means that the road lead into the War Department's Land.

Military features weren't shown on maps sold to civilians, but we can add them back.

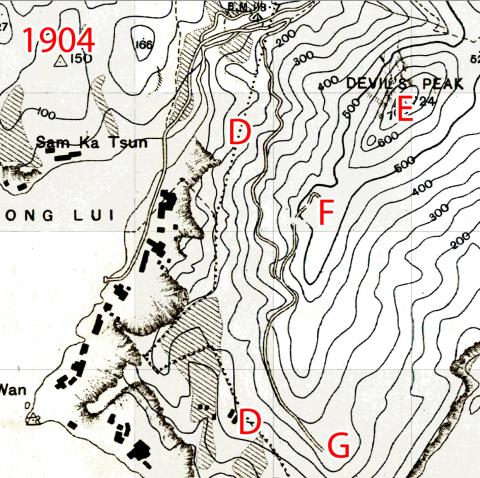

Now we can see that the roads linked the pier to three military sites:

- (E) - Devil's Peak Redoubt

- (F) - Gough Battery

- (G) - Pottinger Battery

Zooming out we can see these three sites overlook Lei Yue Mun / Lyemun Pass (H), the narrow, eastern entrance to Victoria Harbour.

It was an important site the British needed to defend against any foreign navies trying to attack ships in the harbour. In 1898 the British already had several coastal defence batteries on the south side of the pass ("I" on the map, today the site of the Museum of Coastal Defence). After 1898 they could also add gun batteries on its north side.

The new batteries and the redoubt needed easy access during construction and for ongoing maintenance and supply, explaining the need for the pier and road.

The notes on the Gough Battery's page include: "1901: Plans approved, construction commences shortly for a 2 x 6" BL Bty at Devils Peak." As one of the project's first tasks would be to build the pier, it suggests the pier was built around 1901-02, or over 120 years ago.

The fighting in 1941

By 1941, the guns had been removed from the Gough and Pottinger batteries, so they took no part in the fighting. However the pier would have a very important role to play.

The Japanese invaded from the north on 8 December 1941, moving south through the New Territories towards Kowloon and Hong Kong Island. The boundary between the New Territories and Kowloon had a system of trenches, barbed wire, and pillboxes, known as the Gin Drinker's Line. It was hoped that the British troops along that line would hold up the Japanese advance for at least a week.

Instead the Japanese quickly captured the Shing Mun Redoubt in the night of 9 - 10 December. The redoubt was a key part of the Gin Drinker's Line, and its loss sent the British forces into a rapid retreat to Hong Kong Island. Soldiers from the west side of the line - the Royal Scots, the Volunteers, and the Canadians - moved south through the Kowloon peninsula to Tsim Sha Tsui near the Star Ferry, where they boarded boats to cross to the island.

The eastern section of the line was defended by Indian soldiers in the British Army, the Rajputs and the Punjabis. They moved southeast towards the Devil's Peak area, and the Sam Ka Tsuen pier where boats could ferry them over to the island.

Here are some relevant extracts from the Rajputs' War Diary (it calls the pier a jetty):

- Thursday, 11 Dec 1941

- 21:30 - Rang up G.Ops about 2200 hrs and was answered by the G.O.C. who seemed somewhat surprised I was still in my forward positions as he then told me Bde had already withdrawn and told me I could commence my withdrawal.

- Friday, 12 Dec 1941

- 17:45 - "A" Coy reported enemy in strength about 3 coys emerging from re-entrants on his right flank to attack him.

No previous enemy movement had been reported here neither was there any arty fire.

Few minutes later "B" Coy reported enemy in strength about 1. Coy with M.G.s attacking his front.

1. Bty R.A. applies S.O.S. tasks on A Coys front. - 18:15 - "A" Coy reported enemy withdrawing in some disorder never having got through his wire and having suffered heavy casualties. Indicated nullahs in which enemy had withdrawn.

Contacted TYTAM 6" Hows. whose immediate but unpredicted concentration was accurate and devastating.

Continued shelling of those nullahs carried out by No 1 Bty.

- 17:45 - "A" Coy reported enemy in strength about 3 coys emerging from re-entrants on his right flank to attack him.

- Sat, 13 Dec 1941

- 04:30 - Received phone call from Brigadier asking if I was prepared to withdraw entire Bn that night. Replied that that this was rather tall proposition as there was only some 2 hours of darkness left. Also that the enemy has obviously taken a nasty knock as except on "B" Coy's front he'd made no attempt to follow me up to HAI WAN.

I was informed Command ordered a complete withdrawal.

(It was later found that the very precarious situation regarding sea-transport and the very fact that I had extracted the forward elements without being followed up were the two main factors in this decision.)

Coy Comds sent for and orders given as follows at 0500 hrs at shelter.- (a). Pl "B" Coy on BLACK RIDGE to withdraw first and R.V. at jetty with remainder D. Coy. "B" Coy and M.M.Gs. to withdraw next followed by one pl "C" Coy.

- (b). Covering Tps. Two Forward pls "C" Coy. one at HAI WAN GAP and the other on low ground as a lay-back.

- (c). H.Q.W. to evacuate as much baggage and personnel before arrival of Rifle Coys.

- 06:30 - All troops withdrawn except Bn HQrs and covering troops.

- 07:30 - Bn HQrs and covering troops withdrawn without contact. Considerable congestion found at jetty and H.M.S. THRACIAN lying near in and M.T.Bs. at jetty.

Last M.T.B. left at 0745 hrs in Broad daylight.

Still no contact and fortunately no enemy air activity.

Bn. disembarked at ABERDEEN and sent to Bivouac in TYTAM area for 24 hrs rest and refit.

- 04:30 - Received phone call from Brigadier asking if I was prepared to withdraw entire Bn that night. Replied that that this was rather tall proposition as there was only some 2 hours of darkness left. Also that the enemy has obviously taken a nasty knock as except on "B" Coy's front he'd made no attempt to follow me up to HAI WAN.

The retreat to Sam Ka Tsuen and the evacuation by sea - Hong Kong's Dunkirk - was a success.

Post-war

As mentioned above, by 1941 the batteries served by the pier were no longer used. Any hopes they would be refurbished and put back into operation after the war were dashed by the Royal Artillery's survey of Hong Kong in 1946. They concluded that Hong Kong's coastal defence batteries, including the Gough and Pottinger batteries, were no longer needed.

The batteries and the roads that led to them had become redundant, but the pier continued to be a valuable resource for the local villagers. Looking at later maps of the area, the first one I see with roads linking this area to the rest of Kowloon is from 1970, so for several decades after WW2 the pier was their main link to the outside world.

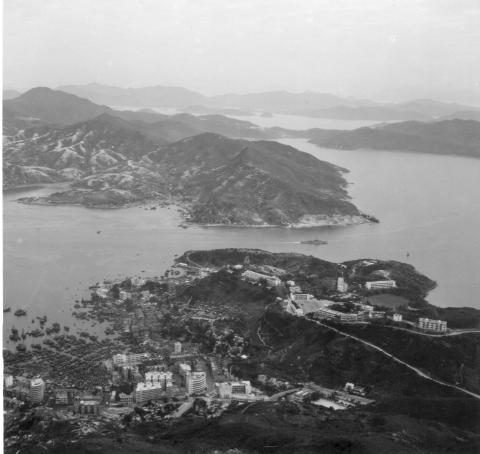

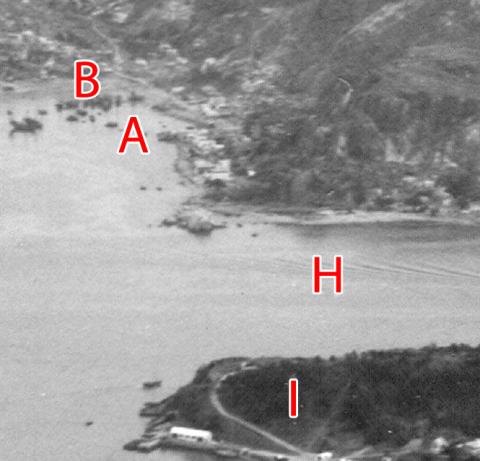

Here's a view of the area from Hong Kong island in 1957;

An enlargement shows the pier (A) and the road bridge (B) are still clear to see:

What remains in 2023?

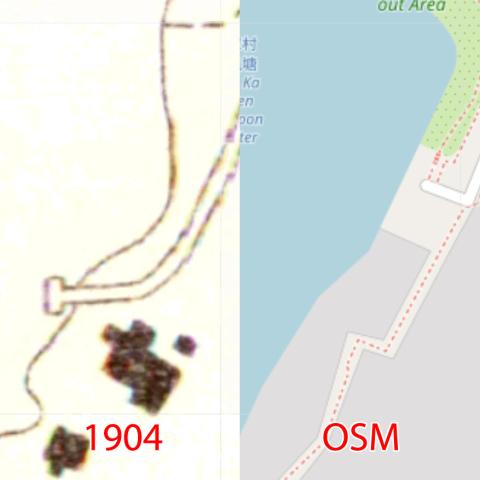

When I first saw that 1904 map, I switched to a modern map of the same area, hoping I'd see the pier.

Alas, no sign of it. The pier looks to have been absorbed into the village at some point, so even if there were any remains they would be hidden beneath the floor of one of the area's many seafood restaurants.

But by chance I was looking at the same area on a different modern map, and on this one there is a clear "T" shape, about where the pier used to stand. Maybe the village had grown out around the pier, but not over it?

How old, exactly?

That last comparison raises a question. The modern map shows the road makes a sharp, 90-degree turn, just before reaching the T of the pier, and the pier is at right-angles to the shore. However on the old map the pier faces in a different direction, and the road curves at a much gentler angle. So was the old map-maker being careless and both maps show the same pier, or was the pier rebuilt at some point with the sharper angle?

Fortunately we have an early aerial survey of the area from 1924 which clearly shows the same 90-degree turn:

It is likely the current pier is the same one shown in the 1924 aerial photos, making it at least 99 years old.

The jury is still out on whether the pier on the 1904 map is really different from the 1924 pier, or if there was a mistake in the 1904 map and the pier is over 120 years old. We'll need further evidence before we can be sure.

It was time to get away from the computer and re-visit Lei Yue Mun to see if we can find any clues in the real world.

Visiting the pier

On arriving at the pier's location, its T-shape is no longer obvious, as the reclaimed land now extends out as far as the front of the pier. Despite that it is still clearly a working pier, as both times I've visited there has been a boat moored alongside, with a steady flow of workers unloading seafood onto trolleys for delivery to the local seafood restaurants.

I wanted to see the pier from the water, hoping that some part of the old pier would still be visible. Luckily there is a small floating platform used by the local boat owners, you can reach by walking across a short gangplank.

From the platform we can look back and towards the end of the pier.

It's the usual jumble of materials we see in village construction, a mix of bricks, concrete, and wood.

But look closer again in the centre of the above crop. Where the outer corner of the 'T' should be there is a very large, and very neatly finished granite block.

Back on land, following the line of the granite block back towards the seashore we can see another of the large, granite blocks, though it is almost completely hidden underneath later construction.

These blocks are much larger, and of a much higher standard, than anything used in the typical villagers' reclamation. I believe they are part of the pier that was built by the British Army some time between 1901 and 1924.

Conclusion

The pre-war pier still exists, and is worth an entry in Hong Kong's record of historic structures:

- Over 99 years old, and possibly over 120 years old (does that make it Kowloon's second oldest surviving pier, after the Lung Tsun Stone Bridge?)

- Played an important role in the fighting in 1941

- The communications hub of the village before it was linked to Kowloon's roads

- Still in use as a working pier today

Unless, of course, I've jumped to a wrong conclusion and conjured up a good story out of my imagination! If you spot any mistakes, or if you can add to the story, please leave a comment below.

Further listening

I joined Annemarie Evans on this week's edition of her Hong Kong Heritage show for a wander around Lei Yue Mun. We took a look at the pier, and at some of the other historic sites in the area. You can listen to the episode on the RTHK website.

For more about the old quarries in this area, listen to Patrick Hase talking about the history of Kowloon. The section about the quarries starts at 4:42.

Further reading

Tony Banham's Not the Slightest Chance is a great reference if you're interested in following the events of December 1941.

All of the maps shown in this week's newsletter came from the excellent Hong Kong Historic Maps website.

The Rajputs' War Diary is available at the UK National Archive, their ref: WO 172/1692

More maps, photos, and notes about the historic sites mentioned above:

Comments

who built the pier

Excellent David. A picky point, but perhaps better to note that, rather than the RE building the pier (on the identity of which I suspect you are correct), the process is less singly attributable. Would it not be better to note that Hakka quarriers, probably from Lei Yue Mun or Cha Kwo Ling, hewed out the granite, and that Hakka or Cantonese labourers working for a local contractor actually built the pier? To the RE goes the design credit, probably the setting out of the site and, at some level or other, site supervision during construction.

If your diagnosis holds up, somewhere on one of those granite blocks is likely to be some sort of incised marker, probably attributing the pier to the same RE unit that left its moniker in Devil's Peak Redoubt.

Best,

StephenD

The road mentioned under B…

The road mentioned under B with a bridge across the water and the pier mentioned under A (hopefully) can be seen in this photo from 1957.

Fascinating read

Thank you David- what a fascinating read!

Professional research

Great thanks for the professional research to put more HKG history to the surface. Linking the topic to the walk and audio are also impressive.

1901 Public Works Report

Reference the Construction of the Pier.

In item 19. Dredging Foreshores in the Report of the Director of Public Works, for the year 1901, the following is mentioned:

The government dredger having been sunk in the harbour on 2 March was successfully raised and after undergoing thorough repairs at the hands of the Dock Company resumed work on 16 September. The dredger was subsequently hired to the Military Authorities for a period of four weeks in connection with the construction of a pier at Chong Lui, near Devil’s Peak.

Sam Ka Tsuen pier

Thank you for the replies and the sharper photo.

StephenD, I haven't found any information about the building of the pier and batteries, but I agree it makes no sense to bring the granite from far away when they had such well-known quarries so close to the site. Have you seen any information about building batteries in Hong Kong that gives an idea of how the building work was split between the RE and local contractors?

Moddsey, that is a great find that confirms work on the pier was underway in 1901. I'd ignored the PWD's reports, thinking that military work wouldn't be covered, so thank you for taking the time to track it down.

Chong Lui is the name of the inlet at Sam Ka Tsuen, shown on the map below above the red "A":

The old pier should be…

The old pier should be visible centre left (left of the two-storey wooden building with a white roof) on this 2010 photo.

Contractors

David - the only HK-related source that springs to mind is...

[Admin - I've moved Stephen's comment over to a new page, as the topic deserves its own thread. Please see: https://gwulo.com/node/59161]

More granite blocks

The granite block shown in the main text is at the northwest corner of the pier, seen from the floating platform:

Down at the southwest corner of the pier there isn't any handy floating platform, but if you lean out over the next-door seafood restaurant's railings you can see the blocks at this corner too. (The blocks look curved in the photos below, but that's just the effect of the wide-angle lens on my phone - the blocks are actually in a straight line.)

120+ years old

One of my questions above is whether the pier we see today is the one built around 1902, or whether the pier was rebuilt between then and 1924. We have an aerial photo of the pier from 1924 that shows it in the same shape and position as later maps, but there is also a map from 1904 that shows the pier in a different shape and facing in a different direction, which causes the uncertainty.

I've found two more early maps that add votes to the "built around 1902" answer.

I'd searched the UK National Archives catalogue for Devil's Peak, thinking I could take a look when I visit the archives in April. This one looked promising:

Description: Devils Peak Sites for Batteries, etc.

In a stroke of luck, I found I'd taken photos of that document "just in case", on a visit back in 2017. Even better, it has maps that show the area as it looked when the British surveyed it in 1899, and another showing their plans for the new pier they would build. Here's a compilation of views of the pier at different times:

As the alignment of the pier in a, b, and d are so similar, I think it is likely that d shows the pier that was built around 1902 and still stands today, and that the different alignment of the pier in c is just an error made when drawing that map.

A Quick Question

Given there was an existing pier in 1899, I am curious if the maps from the National Archives show the nearby quarries at Lyemun?

Sam Ka Tsuen Pier

Sam Ka Tsuen 1973, by Paulo

1958 Map

The pier is also visible on this 1958 map.

1950's Photo

Hi David,

There's a good photo of the pier, dated 1950s, at;

https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/tq57rp52f#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xy…

Judging by the masts sticking out of the water there seem to be two sunken ships in the bay.

Lei Yue Mun Pier wrecks

Interestingly, neither wreck appears on the Emergency Chart, Hong Kong Waters East, HMS Challenger, Cmdr Sabine, Nov-Dec 1945. The survey, one of three large scale surveys by the Challenger team in late 1945, was intended to show all wrecks to assist in clearance work, as well as identify waters safe to navigate. So, this one/these two wrecks is/are evidently not wartime remnants. No wrecks are shown in this location on the Marine Department's E2195, submitted to the UKHO in 1952 identifying all remaining wrecks in the harbour. There's also nothing on the 1960 issue of BA3279, Hong Kong Waters East. So, if 1950s, then c.1953-59. STS Gloria, 1957, put the Tibandjet aground not far distant, so this/these may have been another victim, though this/these because for the masts to have been of the same vessel, sh'd have had to have broken in half. The HKU caption is rubbish, since the photo is clearly taken from up towards Devil's Peak and not from Lei Yue Mun Fort - that may mean their dating is awry too.

StephenD