PREFACE.

This volume is not published in its present form for public sale, but designed as a souvenir to personal friends who have expressed a desire to have copies of these „Letters" for preservation; and I have endeavoured to enhance its value by sketches and photographs of scenery and costumes in the countries through which I passed. The "letter press", I regret to say, is not what it should be, as it was printed before my return from the forms as originally published in the Daily Leader, and abounds in errors resulting from hasty proof-reading, unavoidable in a morning paper. The annexed Errata will rectify some of these most glaring mistakes, but the minor errors in orthography and punctuation are left to the intelligence of the reader to correct for himself.

Addition by handwriting: autographed by author, copy has 7 additional photos than CHS [?]

NUMBER SIXTEEN

Approach to Hong Kong—Safely Landed Under the Protection of a Young Amazon --Wonderful Prosperity of Hong Kong—The Greatest Smuggling Depot in the World—Manners and Customs of the People—The Most Snobbish Place in China--Street Scenes—Sepoys from India—Parsees—Black Policemen—Justice Swift and Sure—A Chinese Jack Cade—Broad Brimmed Hats—Sedan Chairs- Climbing Victoria Peak—Reception to Mr. Seward —A Buckeye Abroad Who Is Creditable to His Country.

HONG KONG, January, 1871

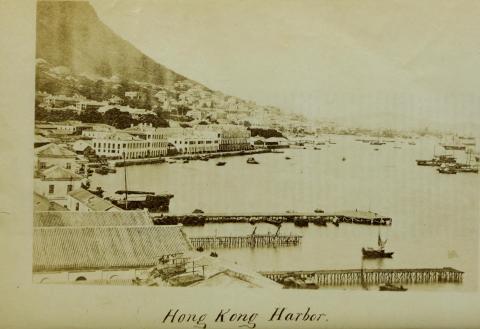

It was a warm and bright Sunday morning when the French steamer „Phase" dropped anchor in the beautiful harbor of Hong Kong, and my impression at the time has been confirmed by a ten days' residence, that this is the most picturesque as well as one of the most spacious harbors in the world. Rio Janeiro is said to resemble it, but neither it nor the Bay of Naples can rival the beauty of the scene before us. The mountain rises abruptly from the water's edge, and is crowned by „Victoria Peak," seventeen hundred feet above the sea. The houses are built tier above tier, and from the water it seems a city of palaces, stretching far up the hill side, and for more than two miles along the shore. Beyond the town, on the left, I see the "Happy Valley," where I can catch a glimpse of the English cemetery embowered in tropical foliage; for with all Its beauty of location Hong Kong is not healthy, and many an American and European who has come to this Eastern land in search of a fortune, remains here in possession only of six feet of Chinese earth.

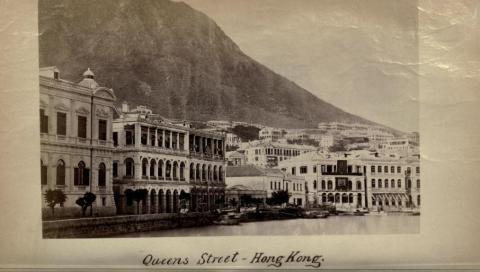

Landing here is but a repetition of the scene at Shanghai, but I have learned something by experience. A hundred sampans surrounded the steamer, some manned by males, but the greater number by females, and the shrill pipes of the women drown the bass tones of their male competitors. I lean over the rail, and before leaving the deck close my contract with a young Amazon to take me ashore, and have no further trouble. See fought her way to my pile of luggage, manfully shouldered trunk and valise, and I had only to follow in her wake to the boat, the crew of which, from a family likeness, I judged to be her mother and sister. In five minutes more I am landed at a fine granite pier, and follow six coolies carrying my luggage, which would be a light load for one Irish porter, to the Hong Kong Hotel, a spacious, airy building, with wide verandas extending round each of its five stories. This city, which is sometimes called the St. Helena of the Chinese seas, has grown very rapidly, and has a most motley population, made up of every European and Asiatic nation. It is not a part of the Chinese Empire, but the island on which it is situated, containing about thirty square miles, was ceded by the Chinese government to Great Britain thirty years ago, and forms the colony of Victoria, with an English Governor and a full set of officials appointed and sent out from home.

The population is about 150,000, and it is growing more rapidly than any other piece in the East. It is a free port, with no custom house or port charges of any description. The sum of five dollars, which a vessel pays on entering the harbor, is returned when she leaves. With a land-locked harbor, safe against any storm, and spacious enough to hold all the navies of Europe, so close to the ocean and ease of access that no pilots are required, Hong Kong has become the central depot for shipping and merchandise on the coast of China. The native population from the main land have made this barren rock their home, and built up a Chinese town of 80,000 people, which stretches along the western shore of the bay, and is creeping through the ravines and up the hillside, attesting the untiring industry, perseverance and enterprise of the native Chinese when in the pursuit of gain. Hong Kong is the postal and financial centre of the Chinese seas, and here are located the heads of mercantile firms, who determine the destination of ships end cargoes composing the foreign trade with China. Trade converges here as to a great centre of attraction. From my room in the hotel I can see ships of war, trading junks and mercantile craft from almost every country. Over twenty steamers are anchored in the harbor, and native vessels in great numbers from the adjoining coast, each differing in shape and color, according to the port they are from, crowd the anchorage on the west side of the harbor. Here are junks from every port between Shantung, 1,200 miles north, and Siam, Singapore, Java and the Philippine Islands. A Chinese sailor will distinguish where they came from by difference in shape and rigging, paint and decoration; and, if honest, may tell you where stout-built junks are lying undisturbed, with a pirate crew, and neatly fitted out with a fresh supply of guns and powder. Only it would not answer to trust him implicitly, for he may belong to a piratical craft himself, and put you on a false scent.

It may be asked what is the secret of this sudden and enormous growth on a barren rock in population and commercial importance, when the main land close by has many commodious harbors, nearer the producing markets and the native purchasers of foreign goods. The answer to this question shows another side of the picture, not creditable to British commercial ethics. When poor China was forced, at the mouth of the cannon, to cede this island, lying in the highway of the immense commerce of Canton River, to Great Britain, she did not dream that it would become the greatest smuggling depot in the world. That the body and soul destroying drug, which she was trying to keep out of the reach of her teeming millions, would here be stored in immense quantities, and smuggled to the main land in spite of all her efforts to prevent that cargoes of foreign goods on which she had the right to levy an import duty, would from this central point be run into every creek and bay along the coast where they could be landed by bribing the officials. That tea, camphor, cassia, sugar and other products of China, which pay an export duty at the consular ports should go to Hong Kong free. This illicit trade which an English writer speaks of as the "encouragement of commerce at the expense of revenue," is neither more or less than smuggling, and from it the fortunes of the Hong Kong merchants have been made. Verily the poor "heathen Chinee" has very few rights which John Bull is bound to respect.

Hong Kong has the reputation of being the most snobbish place in the east, and in my short experience I have seen much to confirm this idea. Being a miniature province with a governor who represents royalty, and a set of tide-writers and hangers-on fresh from the old country, English habits and manners are not only adopted as the standard, but exaggerated, so as to become almost ludicrous. To be a "Royal Britain” here is to worship everything that bears the semblance of royalty—unicorns, lions griffins and crown. The effrontery and arrogance of John Bull is proverbial all over the world, but in the cast the bovine animal roars and bellows in his loudest tone, paws the ground and tosses his head in the most defiant manner. This may be excusable in a nation on "whose dominions the sun never sets." but what shall I say of Americans residing here for a few years, who adopt the tone and air of the cockney, cultivate side whiskers, sneer at everything American, and especially affect to despise Republican institutions. At dinner parties you will hear sentiments expressed by Americans anything but complimentary to their native land, sneers at American consuls and officials abroad, and that, too, in the presence of foreigners. I am almost ashamed to record an instance of snobbery that occurred here not long since. An American merchant, born in Boston, but for some years a resident of Hong Kong, who aspires to social position among the English nobs, said to the Governor of the colony that "he would willingly give ten years of his life if he had only been born an Englishman." The bluff old Governor, disgusted at such flunkeyism, administered a stinging rebuke that brought the mantle of shame to the cheek of the renegade American. That line of Saxe, “Born in Boston needs no second birth," does not apply to him.

This loss of national pride among Americans which the air of China seems to produce, was illustrated last fourth of July by the captain of the Pacific Mail steamer “China”, on her way from Hong Kong to San Francisco. Is was suggested by the Americans abroad that he ought to dress the ship with flags, and in some suitable manner celebrate our national holiday. But the captain declined to do so for fear that the English passengers might take offence. This, too, on an American built steamer, sailing under the American flag, and belonging to a line that was receiving a subsidy of half a million dollars a year from the American government.

I do not say that all Americans in China are like these I have noticed above—but the feeling which I condemn is so common as to give a tone to American society, especially in Hong Kong, and be noticeable to any one fresh from home, who cherishes that amor patriae which, while not blind to our national faults, would at least never parade our soiled linen before our neighbors eyes.

One class of Americans wherever I have met them seem to cherish a deep love and affection for their native land, the Missionaries, There seems to be very little social intimacy between them and the merchants. They give no expensive dinner parties nor entertainments, but devote themselves quietly to their blessed work. They are sometimes refined to sneeringly by their money-making countrymen, whose conduct, as an illustration of christian morality, is not always a bright example to the heathen.

These small communities of Europeans are subject to rules of etiquette as inexorable as the laws of the Medes and Persians. The gentlemen in society being far more numerous than the ladies, it is considered proper for a stranger to call on any or all the ladies without special permission, or even an introduction. If considered an eligible acquaintance, the husband of the lady returns the call, the new-comer is invited to dine, and considered as admitted to terms of social intercourse. If not considered a desirable acquaintance, his call is simply ignored. The Hong Kong club excludes every person who sells goods by retail. He is not considered by the snobs here a gentlemen, no matter how extensive his business or how great his wealth or culture. A. T. Stewart, if residing here, could not become a member of this would-be aristocratic and very exclusive club, which is the only one in the place. The thermometer may stand at 120° in the shade, but a black dress coat must always be worn at dinner, whether ladies are present or not. I was told that in some of the bachelor hongs, as the dwellings attached to the large mercantile houses are called, it is not considered the thing to appear at breakfast even except in full dress. Such snobbishness carries its own penalty and is a subject of ridicule to strangers from every other country than England, instead of impressing them with the wonderful exclusiveness and high breeding of society here.

The streets of Hong Kong are more cosmopolitan than any others I have seen in China. A regiment of red-coated Sepoys from India is stationed here and I frequently meet the soldiers in the street. They are tall, fine looking men, dark complexion, Asiatic profile, keen black eyes, and have the bearing of men who can fight. Their commissioned officers are all Englishmen, but the chevrons on the sleeves show that there is a chance for promotion to a native up to a certain grade. I am told that they are Sikhs from the Paunjaub in Northern India, which did not join in the revolt against the British in 1857. They all wear white helmet-shaped pith hats, which are universal in India.

Here I see for the first time the Parsees, disciples of Zoroaster, and sun-worshippers. They are most numerous in Bombay, but a few can be seen scattered throughout the whole east. They are no darker in complexion than Cubans, but are a larger and finer-looking race, men of education, and first-class merchants. Their dress is European, except the tall Mitre or hat, which is peculiar to the sect. It reminds me of a brown, glazed snuffbox, worn a little on the back of the head, without visor or any protection for the eyes.

The motly population of Hong Kong includes a large proportion of rascals from every clime, and makes a very large number of police necessary, over six hundred, of whom nearly one half are negroes. In answer to my enquiry to-day, one of them told me he "was a subject of the Queen from Jamaica”. He had never been in the United States and thought “there was too much prejudice against color there to suit him."

In the heart of the city is an immense jail with seven hundred inmates, mostly Chinese, who work on the street chained together and guarded by soldiers. Punishment to a Chinaman is swift and sure if caught transgressing the laws. A few days ago a friend of mine arrived on the Pacific Mail steamer “Great Republic," from San Domingo (amended to “San Francisco” by hand writing), and leaving his luggage locked in his stateroom, he took a walk up town. A waiter who was passing his room heard a slightly rustling noise, and looking through the keyhole he espied a Coolie, who had crawled in through the window, rifling the baggage. He gave the alarm and the fellow was secured and taken ashore to the office of the Company. Here he broke away from his captors and dashed through the crowd, but was caught by his pigtail, which streamed out behind in his rapid movement. He was then led by the queue to the Magistrate's office, and within an hour from the time he was first caught, he found himself in the chain gang, with six months before him of hard work.

A Chinese "Jack Cade," before starting out oils his body, wearing only such garments as will readily slip off, and fills his queue with bits of glass. As they rarely carry arrows (amended to “arms” by hand writing) they are not very dangerous, but decidedly slippery customers and hard to hold.

The hats worn by the natives are very odd looking, and quite different from those usually seen in Northern China. It is of bamboo, very light, and often three feet in diameter, curving up from the edge of the brim to the centre like the lid of a tea-pot. In Chinese towns, where the streets are narrow, two such hats cannot pass each other without colliding, and they have to be carried under the arm.

The best institution I have seen in Hong Kong is the Sedan chairs. The doors of the hotel are besieged with them, and they are everywhere to be hired for a very small sum, which is regulated by the city government like the fare of hackney coaches. It is cheaper to ride than go on foot, and they are used by everybody, as the streets are mostly too steep for carriages drawn by horses. They are made of bamboo and cane, very light, and comfortable, with a green canopy to keep off the sun, and supported by bamboo poles about ten feet long, resting on the shoulders of two coolies, who glide rapidly over the ground at a pace between walk and a trot. As I look from my window I see a sailor coming up the street in a chair, with his feet elevated over the "dashboard" and lying back with great dignity, smoking a cigar. Late every night I hear the "won't go home till morning," sung in full chorus by bands of sailors, out on a bender, who sweep through the center of the street arm in arm. The police never seem to interfere with such demonstrations on the part of white men.

A few days ago, with some friends, I ascended to the summit of Victoria Peak, from which there is a magnificent view of the whole island of Hong Kong and many miles out to sea. Four coolies to each chair carried us up the winding path, and in some places the ascent was so steep that I pitied my perspiring "bearers" and got out and walked—a piece of humanity quite unexpected. On the summit is a tall flag-staff, a powerful telescope, and a cannon in charge of a guard, who signals to the town below the approach of every ship long before she can reach the anchorage. He explained to us his system of signals by which the merchants are informed as to the character and nationality of the coming vessel while she is twenty miles away. The cannon is only fired at the approach of a mail steamer or a man-of-war.

While at Hong Kong I was present at a reception given at the American consulate to the Hon. Mr. Seward. It was a very pleasant affair, attended by all the American residents and several prominent English merchants. The venerable ex-Secretary was welcomed very gracefully in a little speech by our consul, D. H. Bailey, Esq., and replied in an address which showed that he has lost none of his ability as a diplomat. He gave the usual credit to commerce of carrying civilization and Christianity to heathen lands, but drew a picture of the future for China in too roseate hues for any one but an optimist, giving the Chinese credit for all the virtues, while he thought them entitled to all the consideration of the most favoured nations. He defended the Burlingame policy, which is especially obnoxious to American merchants in China. It was evident that he does not agree with "Truthful James"—

Before leaving Hong Kong for the "up country," I must express my gratitude to Mr. Bailey and his estimable family for many sets of kindness and courtesy to a stranger. Mr. B. is a Buckeye from Cincinnati, a lawyer of ability, and his eminent social qualities and liberal culture render him the most creditable representative of our country abroad that I have anywhere had the pleasure of meeting. W. P. F.

Source: "Round the world." : Letters from Japan, China, India, and Egypt : Fogg, Wm. Perry (William Perry), b. 1826 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive, published 1872 in Cleveland, Ohio.

Addendum

As mentionend above, photos were affixed into the book. On the internet, three copies are available. In the current book, this photo is used for the illustration of Hong Kong:

To me it's totally unclear why the author selected this one.

In other copies, this photo was used:

Although labelled incorrectly, it seems to fit better to what the author reported.

Mr. Fogg

When I first found this letter/book, the name Fogg was quite familiar for me. There is :"Around the World in Eighty Days", an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. The protagonist is named Phileas Fogg.

Possibly pure coincidence, but who knows?

some matinee and c.1870s background

Quite likely related. Wikipedia also quoted two books which detailed more findings. One of them here.

The 2nd opening paragraph on W. P. Fogg's landing in 1871 also reminds us of the adventure-humour flavour of Jules Verne's book, almost with dramatic pictures in mind. (sarcastic also)

Or this is some common style on novels during that 19th century period ? But I could name one book only, which is about a boating trip on the Thames (c. late 1880s).