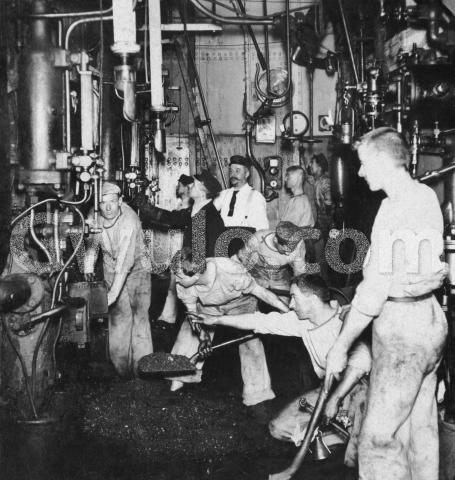

Where: As the title says, we're inside the "stoke-hole"* in the Royal Navy's HMS Terrible, a Powerful class of protected cruiser [1]. The men are feeding coal to the fire that heats the boilers, generating the steam that powered the ship's engines. (* - This photo describes it as a "stoke-hole", but the Navy book quoted below calls it a "stokehold".)

When: The copyright date on the photo is 1902.

A book about the ship, The commission of H.M.S. "Terrible," 1898-1902 [2], says the Terrible first arrived in Hong Kong on 8th May, 1900 to join the China station. It made several more visits to Hong Kong over the next few years, returning for its longest stay on Jan 4 1902. There were a couple of short trips away in June and July that year, then the Terrible left Hong Kong for good on July 29th, setting sail for Britain.

Since it spent so long in Hong Kong in 1902, there's a good chance that's when the photo was taken.

|

Ideas if you'd like to help Gwulo... #4. Answer a question (20 minutes) Each week's newsletter includes questions posted to the website during the week. You can find then below in the section titled "Also on Gwulo.com this week." If you spot any you can answer, please let us know in the comments. Thanks for helping! |

Who: The book "The commission of ..." gives an idea of who we can see in this photo:

The engineer officers graduate as engineer students at the Keyham Engineering College, Devonport Dockyard, before receiving the King's Commission as assistant engineers, while their subordinates—engine-room artificers and stokers — on joining, receive practical training at the respective naval depots. The stokers are a semi-military body, as they undergo a special course of military instruction, and perform the annual musketry practice.

I guess the five men in the light-coloured clothing are some of the stokers.

Can any Navy experts suggest who the two more senior men in the background would have been?

The book also gives us some glimpses of the stoker's life. Early in the book they describe the trials to prove the ship's performance:

On September 15th the ship was ready to proceed, and officials representing the departments interested assembled on board to note the result of this final full-power race against speed and time ; 25,000 horse-power having to be maintained for four hours, and the ship also having to travel 100 miles in that limited time to satisfy her judges.

To propel a constructed mass of over 14,000 tons weight through the water at 25 miles per hour requires both physical and mechanical endurance of no mean order. The powerful engines derive their enormous horse-power from forty-eight boilers of the Belleville water-tube type, which were then receiving a rabid condemnation from the "anti-water-tubists." The coal expenditure for this special run averaged 25 tons per hour, which may appear a great quantity to consume, but it must be remembered that the coal-carrying capacity of the ship is over 3000 tons, and sufficiently large in proportion even to this consumption. It would require a personal visit into the stokeholds and engine-rooms fully to realize what a full-speed trial means in a large modem man-of-war. Owing to the necessity of having an armoured protective deck over the engines and boilers, it follows that, for want of space, the piston stroke must be considerably reduced, so that these huge engines were compelled to revolve at the rate of 110 revolutions per minute to obtain the required speed. In the stokeholds it might be truly said there was as hazardous a risk to be faced as on a battlefield for those men who fed the furnaces. A mishap, fortunately rare, occurring below when steaming at full speed, would probably produce disastrous results. As steam was the greatest factor upon which success depended, the day was a real stokers' day, and three hundred of these men had practically the result of the race in their hands. Fleet-Engineer Rees was in the position of trainer, as he knew what the ship could, and should, do, providing everything below went well ; but no one envied the position of this officer on trial days — this day in particular.

The stoker's job was to keep the fires fed with coal, moving "25 tons per hour" by hand.

The hazardous risk mentioned above became reality later in the report:

The passage both ways was being conducted at economical speed — twelve knots per hour — under very favourable conditions, when, without the slightest warning to indicate weakness, a water-tube in one of the boilers suddenly split, the full 180-lb. pressure of escaping steam violently blowing the fires from the furnace into the stokehold, the door of which had been inadvertently opened. Several men were badly scalded and burnt, one stoker (Edward Sullivan) so severely that he died a few hours afterwards. It is worthy of record that Stoker Parham, at considerable personal risk and entirely acting on his own initiative, shut off the main stop-valve of the damaged boiler, thereby minimizing the danger in that stokehold. For this service he was afterwards highly commended by the *' Court of Inquiry," and promoted.

Even under normal circumstances, the stoker's life wasn't an easy one:

By noon, the 26th, the Grand Canaries, one of the few remaining links with the past colonial greatness of Spain, had been left well astern, and so had apparently the temperate climate; for real tropical weather had penetrated to a latitude far beyond the usual tropical limits, causing a general desire to camp out on deck both night and day. The heat below was so intense that the full benefit of a Turkish bath might be obtained in the auxiliary engine-room where the temperature then registered over 130 degrees, the stoker on watch finding even his bathing drawers a superfluous garment. One stoker humorously described the stokehold as being a training home, for a certain position, at a certain place, in another world. That may be. Various ranks and ratings are often described as the backbone of the Royal Navy — a much abused and undesirable phrase. Yet few who are cognizant of the conditions under which the engineering staff perform their duty would deny that title (if it must be used) to them — engineers, artificers, and stokers alike, who, whether at sea or in harbour, in torrid or temperate climes, in peace time or war, have always risky and arduous duties to perform.

What: Coal!

Though older sailors would still remember sails and rigging, in 1902 coal and steam powered the Navy's ships. These young stokers probably thought sail was terribly old-fashioned and coal was the fuel of the future, but coal's days were already numbered. By the end of World War I just sixteen years later, the Navy had switched to oil to fuel its ships.

Coal had a couple of strong points in its favour. First, Britain's coal mines could produce all the coal the Navy needed, whereas it would have to rely on foreign countries to supply oil. Second, coal wouldn't explode it was hit by a shell, so the ship's coal bunkers acted as an extra protective layer over the core of boilers, engines, and magazines.

But oil's advantages won in the end. The big one was the ease and speed of refuelling ships with oil, vs. the slow, manual job of loading coal. Second was the ease of delivering fuel to the engines - no more shoveling coal like we see here, which meant a lot less men were needed on each ship.

I'm hoping some of our readers can tell us more about the men and equipment in this scene.

Regards, David

Trivia: This photo was originally sold in America as a stereoview card:

The Art Nouveau (Platino) Stereograph

C.H. Graves, Publisher, Phila., U.S.A.

115. In the stoke-hole of H.M.S. Terrible. Hong Kong, China.

Copyright 1902 by C.H. Graves

The Universal Photo Art Co.

Philadelphia, Naperville, Ill.

|

Also on Gwulo.com this week:

|

Gwulo photo ID: A101

References:

- HMS Terrible (1895): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Terrible_%281895%29

- The commission of H.M.S. "Terrible," 1898-1902: https://archive.org/details/commissionhmste00crowgoog

Comments

In the stoke hole

By coincidence a new book covers the same subject.

From Amazon UK

Down Amongst the Black Gang: The World and Workplace of RMS Titanic's Stokers-Paperback

by Richard P. de Kerbrech

Down in the fiery belly of the luxury liners of the Titanic era, a world away from the first-class dining rooms and sedate tours of the deck, toiled the ‘black gang’. Their work was gruelling and hot, and here de Kerbrech introduces the reader to the dimly lit world and workplace of Titanic’s stokers. Beginning with a journey around some of the major elements of machinery that one might encounter in the giant ships’ engine and boiler rooms, the sheer skill and strength that a man in this employ must have had is brought to the fore. The human side of working for Titanic and her contemporaries is also explored through an investigation of stokers’ duties, their environment and conditions: what it was like to be one of them. An oft-ignored part of Titanic’s story, the importance of the black gang and the job they performed is brought to life, making poignant their fate on the maiden crossing of Titanic. This certainly is a book that no Titanic-era shipping historian or researcher should be without.

Photos of HMS Terrible

Here are a few photos copied from the book "The commission of ..." mentioned above.

working conditions

The working conditions for the stokers were extreme. A survey of 1906 made by Bernhard Nocht, a doctor at Hamburg harbour, claimed the suicide rate of stokers to be up to 20% higher than the average. Heat, steam, darkness, constricted working space and the heavy coal load caused heatstroke, exhaustion, dehydration and psychological disorders. Narrations of travellers on a steamer to Asia sometimes give an account of stokers who simply came up from their hell and stepped overboard without a warning - to the bystanders horror. The situation on warships seems to have been much better due to restricted working hours. Many steamship companies employed Chinese stokers.

H.M.S. Terrible 1900-1902

My Grandad

the stoker nearest to the camera is my Grandfather, Thomas Aubrey Smith. He erred throughout the commission of HMS Terrible so saw service in South Africa as well as China. He died in 1927. Two of his sons, one my father, went on to serve in the Royal Navy as well. I am a naval historian. I am very proud of my grandfather and have the stereoview that this was taken from. He also acted as diver whilst in China as well as serving in the Naval Brigade during The Boxer rebellion, as it was known in the UK. Every member of the crew was given a copy of the 'commission of the HMS Terrible' written by MAA Crowe. Our family copy was lost years ago but I have a couple of copies, one an original and the other a facsimile.Its a surprisingly good read with most of the crew listed. The Captain, Sir Percy Scott was instrumental in improving Naval gunnery but upset a few senior officers along the way.

re: My Grandad

Thanks Bob, it's great to be able to put a name to at least one of the people in this photo. Any chance you can identify any of the others?

Regards, David

Re. My grandad

no chance I’m afraid. It was pure luck I recognised my grandad. It is only one of two photos I have of him. At the time I first saw it, one of his children was still alive and she confirmed it but als, they are all passed on now.

Coal fired vessels

Firing steam boilers using hand-shovelled coal still continues today on steam locomotives mainly on preserved tourist railways in Australia, USA and Europe, notably in the UK. There are also female ‘Firemen’ on some railways before they graduate to ‘Drivers.’

Land based boilers being hand-fired can still be seen in a few steam engine museums in the UK and elsewhere.

Hand firing marine boilers has mainly died out, but in the early 1990s a coal-fired steam launch could be seen at Hebe Haven on weekends.

A recent build, ‘The Vital Spark’ had a vertical boiler and a twin-cylinder steam engine with associated pumps and condenser, driving a screw propeller.

Those invited on board were expected to fully participate in the experience, and shovel coal into the boiler at appropriate times directed by the builder/owner during voyages around Hebe Haven’s sheltered waters. The steam whistle was frequently used to wake-up Sunday’s late sleepers tucked up in their moored cruisers and yachts.

A commercial coal-fired bulk carrier visited Hong Kong in the 1980s during a voyage from Australia back to its builder in Japan. The vessel carried a full load of coal for unloading at a power station in Hong Kong while consuming some of its load to fuel its own steam boilers.

However, this was a modern ship, the ‘S.S. River Boyne,’ using mechanically driven chain-grate stokers to fuel the boilers feeding steam to the propulsion turbines.

From recollection it was one of a unique pair of bulk-carriers conceived for use between Australian coast ports. I believe that the concept was not repeated.

A visit on board was made while it was in Hong Kong, which included a detailed tour of the unique boiler/engine rooms.

Unfortunately, the graphically emblazoned tee-shirt showing the chain-grate coal-feeders etc I was given did not survived enthusiastic washing by maids.