The funeral processions were very dramatic. A band came first,

playing weird sad music, then the coffin, carried on poles on

men's shoulders, and following it the mourners, all dressed in white

and sack cloth, their heads covered in large white hoods. They cried

and wailed at the tops of their voices, and had to be supported by

servants, in case they should collapse. These people were often

professional mourners who had been hired by the family, and the

more noise they made, the more honour to the dead person.

Then came a large framed photograph of the deceased, carried

on high for all to see. And finally all sorts ofmarvellous things

made of white paper, carried on poles, animals, birds and flowers,

to be burnt at the funeral.

Chinese graves were very elaborate and beautiful. They were dotted

about on the slopes of hills in the New Territories, and were made

of carved stone, looking almost like wide chairs leaning against the

hillside with arms enclosing a stone floor. In the centre of the

gravestone was a door, behind which was the coffin, and on the

stone floor in front stood little vases with joss sticks in them.

In our early days in Hong Kong we often saw women with bound

feet, wearing tiny embroidered shoes. They moved slowly, leaning

on the arms of servant girls, one on each side, because they could

not walk alone.

In those days Chinese ladies wore high necked jackets and long

skirts, beautifully coloured and embroidered. On their heads they

wore wide bands of embroidered silk, in front only, so as not to

disturbtheir buns and hairpins at the back. They wore earrings and bracelets, of jade and gold. The gentlemen wore jackets and long

gowns, and black skullcaps with a red pompom on top. Both sexes I

think wore soft shoes.

By the time I left Hong Kong, the women were wearing cheong sam,

tight fitting dresses with skirts split up the sides, so attractive on

slim Chinese figures. The men by then were dressed in foreign

suits.

In 1922 the Prince of Wales visited Hong Kong on his Far Eastern

tour. Never was there such excitement, or tremendous preparations.

There were receptions and parades for him, and firecrackers; and

wonderful decorations, especially at night when all the Royal Naval Fleet in the Harbour were outlined in lights and buildings were

ornamented with large crowns made of electric lights.

The Girl Guides paraded for the Prince on Murray Parade Ground,

a proud occasion for usI And on another day we went with our

school to be inspected by the Prince, and the Governor, Sir

Reginald Stubbs.

Murray Parade ground was a great place for parades. Empire Day,

May 24th, was always celebrated with great ceremonial, also the

King's Birthday in June, when the Governor inspected the Troops,

the Navy, Marines and Police. He used to look splendid in his white

uniform and plumed helmet.

We grew up in an atmosphere of military bands playing stirring

music and soldiers drilling and marching. This was part of a British Colony, and we were immensely proud of being a small portion of

the great British Empire. England was always called "Home" with

a capital "H", and people would talk of "going Home on leave".

Mamma would tell us nostalgically of the beautiful English countryside

with its wild flowers.

But to Audrey and me, England was just a name. Hong Kong was

our home. Living among the Chinese as we did, we felt an affinity

with them, and admired their commonsense, patience, courtesy

and humour. We seemed to laugh at the same things. Our Amah

was the soul of kindness and loyalty, and could never do enough for our mother and us.

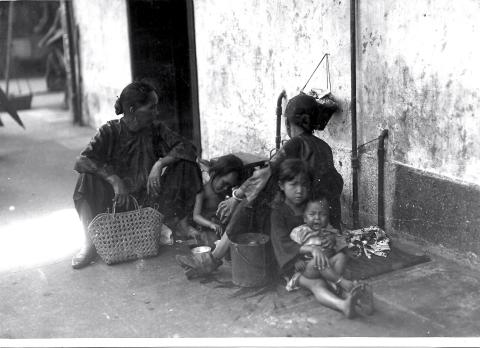

We grew up beside the Chinese noise and exuberance, their shouting,

chanting, firecrackers, music, the hawkers calling out their wares; the

beggars calling "Cumshawl", the rickshaw coolies - "Shaw?", and

the chair coolies - "chair?".

Perhaps Mamma never quite got used to all this. She was always

afraid that we might catch some dreadful disease; and it was

ages before she would allow us to go to the Chinese New Year Fair,

and then only when we had promised to be careful and not let

anyone bump into us! We all had to be vaccinated against smallpox

regularly every few years, and if there was an epidemic of it we got an extra vaccination. Or if a cholera or typhoid or some

such epidemic, we were inoculated against them.

Police men were much in evidence, most of them Chinese, or

large Sikhs with turbans and black beards; the Superintendents

and Inspectors being British. There had to be a good Police force in

such a place as Hong Kong, where bad characters could come and

go quite easily over the Border. Still, there were many robberies,

and we were careful to hold our handbags tightly.

Part of the fascination of Hong Kong lay in the mixture of many

races of people, ours and the Chinese, and the Portuguese, the

Eurasians and all the others.