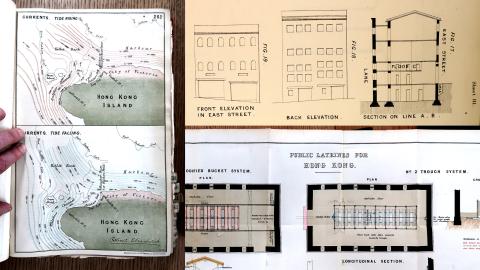

Colourful maps and sketches, and rare views inside Hong Kong’s early tenement housing are bonuses in Mr Chadwick’s report on ‘the Sanitary Condition of Hong Kong’. We’ll take a look at all of the above, plus the old night-soil collections and the 19th-century revolution in understanding disease, in Gwulo’s latest YouTube video.

Comments

Water analyis

Thank you, David, for this interesting presentation. When you talked about water quality, you said that bacteriological analyses would have given a better insight compared to chemical analysis. This is, of course, correct, but these analyses were difficult and possibly not available in Hong Kong at the time when the report was written. Additionally, you mentioned the still widely accepted "Miasma Theory". In the analysis report you presented, "Smell" is the first column after origin and date. As you said, many people at that time still believed that diseases came from bad air (Malaria originated from the medieval Italian mala aria which simply means bad air).

However, some chemical parameters also give information about the water quality. Contamination of water results either from geogenic and/or anthropogenic sources. Geogenic (as the name indicates) contamination comes from the rocks underground where the wells are drilled into. On Hong Kong Island, the most abundant rock is granite, which will not leach a lot into groundwater. An indicator of that is chloride, and it is mostly present only in low concentrations.

Water pollution in Hong Kong, therefore, mainly comes from human activities. I guess we can exclude animals (cattle) in this context. Although "night soil" was collected, certainly a lot of human excrement was discarded "behind the next bush". This leached into the groundwater and was found in the wells. A (today) commonly used parameter for that is phosphate. Also, free ammonia indicates human activities.

No values are given for phosphate. But I think "heavy and very heavy traces" indicate poor water quality. It works better for ammonia where we have analytical results. Values are given in ppm which is approximately the same concentration as mg/l. The EU limit value for groundwater is 0,5 mg/l. Water with concentrations above is usually not regarded as a suitable source of human drinking water.

So, even without bacteriological investigation, the chemical analysis revealed a good insight into water quality, even with regard to human health risks.

One last remark: Even the "Miasma believers" will feel affirmed. Example:

No 5 well at Hollywell Road

Smell - distinct

phosphate - very heavy traces

free ammonia - 1,72 ppm

This, of course, does not work in every case:

No 11 well in Yu Yam Lane

Smell - faint

phosphate - heavy traces

free ammonia - 8.6 ppm

re: Water analysis

Thanks Klaus, that's a good point. I found a WHO document that says "Natural levels in groundwaters are usually below 0.2 mg of ammonia per litre.", or appx 0.2 ppm.

It also says that "The presence of ammonia at higher than geogenic levels is an important indicator of faecal pollution.", so it is very likely the wells shown above were contaminated by sewage.

What I haven't found is when the link between ammonia levels in drinking water and contamination by sewage was widely understood, and used as a way to monitor the quality of drinking water. Was it already widely known when Chadwick was writing his report, and so he didn't feel the need to explain it, or was it something that came later? Have you seen anything about that?

In Chadwick's note about the well-water analyses he's very clear that the water was contaminated, but he doesn't explain how the numbers make that clear.

Re: Water analysis

Interest in the determination of water quality started with the growth of the cities in England, mainly London. In the 1840s and 1850s, water-supplying companies started to deliver water to people, often of poor quality. Chemists tried to find out suitable parameters for water quality. I think that the mechanisms were not fully understood, but already in 1852 it was referred to:

the sulphides and the ammonia that most people agreed were the most harmful materials in polluted water.

It is difficult to find out specific dates when ammonia analysis started, but I think that it was common in the 1860s (at least in London). [In a PhD thesis, I found that in Berlin in 1870, ammonia was a common parameter in water analysis.]

Some information about the history of early water analysis can be found in A Science of Impurity, but it is a bit difficult to read.

Re: Water analysis

Thanks Klaus, that is a good resource to know about, and shows that ammonia was already used as a measure of pollution in water back in the 1850s.