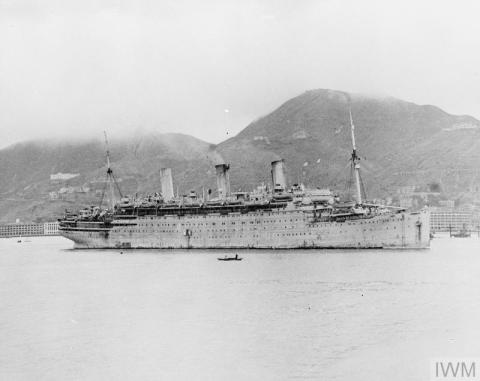

In September 1945, thousands of recently released POWs and civilian internees were sailing away from Hong Kong, heading towards home, family and a chance to recuperate from the hardships of the recent years.

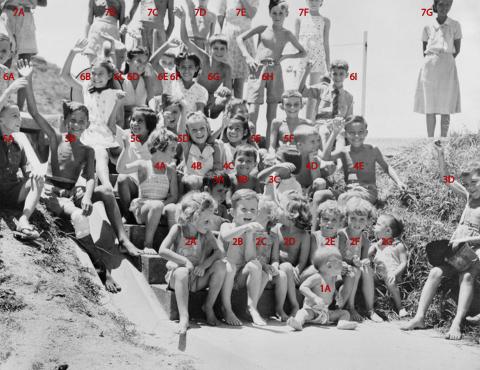

Among the group sailing on the Empress of Australia was widowed mother Una Brown and her young daughter Annette. Born in 1940, most of Annette's short life to that point had been spent within the confines of Stanley Internment Camp. She appears in this photo taken at the camp shortly after the Japanese surrender. (Annette is sitting at front left, labelled 2A).

Below, Annette shares her family's memories of the trip from Hong Kong to Australia.

Una Brown & daughter Annette

Our journey from Hong Kong (Stanley Camp) to Australia Sept/Oct 1945

We sailed from Hong Kong on the Empress of Australia at 7:00am on the 11th September 1945.

The next day my mother wrote to her Australian Aunt Edie, her mother’s sister, from on board the ship:

“Well, here we are on our way to we don’t know where – Manila is our first stop (tomorrow) so maybe then we’ll know more about our fate.

I’ve put down for Australia so will you please let us come and stay with you until I can get settled. Honestly, I really don’t know what I’m going to do, but anything I find in the way of work I’m sure will be sufficient to allow Annette and me to live a more comfortable life and give Annette better food than we’ve been used to these last awful years. Aunty and Uncle, I do so hate asking if I can come to you but I’m absolutely lost, no Harold or Mum to go to -- oh! Now is the time we war widows are beginning to realise what really has happened.

I’m so hoping I’ll be able to receive news of Jack ((Mum’s younger brother)) in Manila – so longing to see or hear of him again. I feel quite sure he must be safe but there is always that ‘but’.

All I have saved are my private papers and snaps, plus a few odds and ends and one or two worn out dresses – an absolute tramp now. Never mind, fate may have something nice in store. For the present all I want to do is try and forget the past.

Everyone on board is absolutely grand to us all. We are nine in a cabin, in three triple decker bunk beds, but that doesn’t matter at all – we put up with almost anything after some of our experiences. Annette saw her first picture today – she was rather afraid of it – the first was a Donald Duck (she liked that) but the other was a pirate picture and the children were rather afraid of it.

It’s rather difficult watching the children on board – there must be thousands of us and if we don’t watch them carefully, they get lost!”

On the 13th we arrived in Manila in the Philippines, which had been regained by the Allies by mid-January 1945.

Mum was horrified at the shipping destruction still evident in the harbour from the Japanese bombing of a few years earlier. She said it looked like a graveyard of ships. Wrecks of large vessels were everywhere; many of them had sunk leaving just their masts and superstructure showing. That evening we drew up alongside the battered wharf, where the troops disembarked. They were taken to a rest camp for a fortnight’s recuperation before final repatriation. The following morning, we moved out into the bay and anchored to a large wreck used as a buoy. Mum counted the ships and recorded them, in shorthand, on a small piece of paper. She said there were 257 or more, plus two aircraft carriers and two hospital ships, one of them from New Zealand.

The Hong Kong volunteers who had been prisoners of war and transported to work-camps in Japan arrived in Manila at midnight on the 14th. Mum was overjoyed to hear that her younger brother, Jack, was safe.

On the 18th we returned to the wharf to take up 1,000 more troops and sailed on to Singapore where we had to leave the ship, as she was going to England and we were headed for Australia. As our small group were gathered at the top of the gangway preparing to disembark, Mum noticed a very well-dressed lady and gentleman at the bottom of the steps, just about to embark. We waited for them but they stood back and beckoned us down, shaking each one of us by the hand and saying it was an honour to meet us. They were Lord and Lady Mountbatten, who were boarding the ship to return to England.

When I think back about the Empress of Australia, the thing I remember most is my delighted fascination with a glass counter on the ship. I would stand, for hours it seemed to me, staring wide-eyed at the trinkets under the glass. It was as if a magician had cast a spell, waved his hand, and suddenly the magical bits and pieces appeared before me. Day after day I was drawn to this counter just to stand and gaze at the treasures under the glass. The Empress had been a passenger liner before she was converted to a troop ship, and this magical place was a gift shop.

When we left the Empress in Singapore, we stood on the wharf feeling confused and not knowing where we were to sleep that night as our new ship, the transport vessel Tamaroa was not ready for us to board. A Dutch hospital ship was berthed at the wharf and the captain very kindly invited us onboard to spend the night on his ship.

Finally, we were able to board the Tamaroa and were on our way once again. Also on our ship were some of the Australian Army's 8th Division, ex-prisoners of war who were being returned home to Australia.

My mother wrote a letter “at sea” on 2nd October:

“Well, we’re definitely on our way to Australia at last. Fremantle is the first port of call – how I do hope I’ve done the right thing in coming to you all – I do hope I won’t be too much of a nuisance, and I’m so longing to see you, one and all.

Everyone on board is very kind to us. It’s such a treat having hot running water – to have running water at all seems grand, but HOT water after 3½ years is more than grand! Fresh fruit is another thing I appreciate and, of course, it’s so civilised to sit at tables with proper cutlery once more – had almost forgotten such a life existed but now it seems absolutely impossible that we existed for the last 3½ years on what we did.

Annette is getting very spoilt with all the ‘Diggers’ – suppose it’s because she is so fair and they haven’t seen white kiddies for so long.”

Notes on 7th October:

“The children had a lovely party, and sports, yesterday. They had a grand time. We women all spend quite a lot of time sewing and mending for the men on board and they do appreciate it, too.

I’m beginning to worry quite a lot now that we are getting so close to Melbourne – I do hope everyone is safe and all our families complete after these awful years – we had enough in Hong Kong without any more sadness, didn’t we?”

When we had left our home in Kowloon when the Japanese attacked in 1941, Mum had only taken a few necessary items with her, including things for a young child. She thought she would be able to return for more. But she was never able to. We never saw our home again. Apart from a few items that other people had kindly retrieved from our flat for us, we had entered captivity with very little in the way of clothing or possessions.

On the Tamaroa Mum learned that the Red Cross would be providing us with some clothing in Fremantle. She also wrote in her notes for the 7th October,

“The Red Cross have promised us clothes in Fremantle so I hope I can have a pair of shoes, especially for Annette.”

Mum had been wearing shoes made from parts of old rubber tyres for the soles, with wide canvas straps across the top. Like most of the growing children, I had run around the camp in bare feet.

Apart from that contact with the Red Cross, Mum received no more help from authorities. There was no such thing as trauma counselling in those days.

My poor mother had such deep worries and concerns at that time but I was just a young child.

Fortunately, Mum had kept her passport with her important papers so she had it with her in the camp. On the renewal page is the following entry.

“Bearer is now interned in the Military Internment Camp, Hong Kong. This passport is renewed for the purpose of assisting her to establish her identity until such time as she is able to obtain a valid renewal or re-issue of the said passport.”

There is another addition on page two of the passport, namely – mine! I was added on the 21st May 1943, under the “Children – Enfants” section.

Mum’s passport is an interesting document showing a history of her travels since 1928. It has many passport stamps, but the stamp I love best says,

“Seen by Customs

10th October 1945

Fremantle, W.A.”

We sailed on to Melbourne, arriving at Princes Pier, Port Melbourne, on 16th October. There was a report the next day on page 4 of the Melbourne Argus about the arrival of the Tamaroa. It says there were several thousand people assembled outside the wharf gates to welcome home prisoners of war from Singapore. Our ship berthed to the accompaniment of ships’ sirens, cheering, flag-waving and popular tunes from a military band. A small number of civilian internees and several children also disembarked. My mother and I were two of those internees. I did not know it at the time, but I was in fact “home”.

A cousin met us and drove us to Williamstown, where we were to live for just over a year. What absolute delights awaited me there! Our aunt radiated warmth and happiness and showered us with her love. At five years old all I remembered was the camp. Now I was bewildered by my new surroundings but also wide-eyed at all the wonderful things my aunt had, and at all the houses with beautiful gardens around them! I thought Williamstown was a magical place!

Aunt Edie would smile sweetly and look lovingly at me in her gentle fashion, her head inclined slightly to one side. Often when she pottered around in the kitchen I would watch in amazement as she washed dishes in a bowl filled with hot water. I learned to help wash and dry the dishes, handling each piece with extreme care lest I should damage one. They were stored in a “dresser” or wall unit with a cupboard underneath and open shelves on top. The shelving had a little fence of ornately sculptured wood across the front and little grooves to place the dishes in. There were hooks to hang the cups from. We didn’t have to share only one tin mug now! How beautiful it all looked when all the pieces were neatly in place. I marvelled at the variety of utensils in that kitchen, compared to the tins with wire handles and odds and ends that I had been used to. And when we went out for afternoon tea, we no longer had to take our own tin mugs, plates and spoons etc!

Aunty Edie was also my saviour as far as mealtimes were concerned. I still did not have a very big appetite; I guess my stomach had shrunk in the camp. I had also developed pneumonia twice, within weeks of arrival, and had been in hospital. Dear Aunt Edie used to sit next to me at the dining table, in front of the brightly burning log fire in the fire-place. She kept her gentle eye on me and when she saw me struggling with something I obviously did not want to eat, she would sneak the offending food from my plate and wrap it quietly on her lap under the table top, in newspaper parcels. Poor Mum! She did so want me to eat the nutritious food so that I would regain my health and strength but, as she did not want to upset her aunt, she kept quiet.

It wasn’t long before Mum found employment. She had become friendly with a gentleman returning to Australia on our ship. His wife had been working as a stenographer for an accounting firm while he was away overseas, but she intended to leave her job now that he was coming home. Mum successfully applied for this position. In a few days she was working for a very friendly firm of accountants in Little Collins Street, Melbourne.

We didn’t return to Hong Kong to live. Mum met an ex-serviceman who had been on the Burma Railway and in Changi. They married twelve months later and we moved into our new home. A very simple thing I saw when I opened the bathroom door meant the world to me: my new Dad had installed a shiny metal toothbrush holder and hanging in it were three toothbrushes – one for Mum, one for him, and one for me! I knew then that I had been accepted into this new family.

I was very fortunate to have had my mother tell me her stories over the years. I used to take a notepad with me when I met her weekly for lunch and enthusiastically wrote down details of her and her brothers growing up in Hong Kong. My children wanted me to “write it all down” properly and so I started writing life stories. I realised I needed to explain why my English, Scottish and Australian family was in Hong Kong, so my writing is developing into a family history book, with Hong Kong as the central story.

A big thankyou to Annette for sharing her family's stories with us.

For more information about these events, I suggest :

- Annette has previously written about the shorter journey from Stanley Camp to the Empress of Australia

- Read other peoples' accounts of the events on 10 Sep 1945 and 11 Sep 1945

Comments

Empress of Australia

I enjoyed the piece by Annette on repatriation on the Empress of Australia and would like to add a little to that story from my book My Beautiful Island - https://gwulo.com/node/56026

Best wishes, Chris