A week or two ago I launched my new book, 'Jack Jones, A True Friend to China' at a meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society at the Helena May. This is the story of the Friends Ambulance Unit 'China Convoy' and how it distributed medical aid in China throughout the nineteen forties, as told in the FAU newsletter writings of Jack Jones, its transport director. Jack was later to write a world best selling 'Suzie Wong' story called, 'A Woman of Bangkok, beating Richard Mason to publication by just one year.

My weighty new book of 400 pages is available at the St John's Cathedral Bookstore, and soon in the USA and UK. Enquiries please to me at arhicks56@hotmail.com. The story is of course of direct relevance to Hong Kong especially as in the later years HK became the headquarters and port of access to China for the FAU.

The book includes over 500 contemporary photos, mostly never before seen, including several of Hong Kong taken by a departing FAU couple who were staying in the QMH flat of Dr Elizabeth Tang (Han Suyin) who had just completed her many splendoured novel.

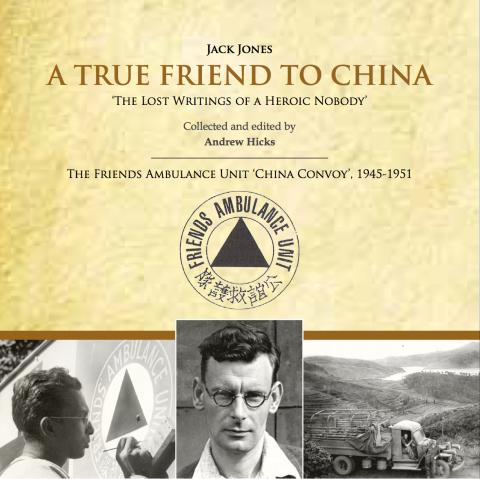

An image of the cover appears below.

The China Convoy makes for a great adventure story as told by the sparkling and always scurrilous Jack Jones. It is also a rare example of men from the west immersing themselves in China but not peddling guns, drugs or bibles, nor seeking commercial or political advantage.

The FAU strongly influenced the emerging Oxfam in creating a new model for relief and development and might itself be called the first ever independent NGO working in that field. Yet this is the first book on the subject since 1947.

Jack Jones' Escape from Chungking to Hong Kong in 1951

My new book, A TRUE FRIEND TO CHINA, tells the story of Jack Jones' service with the Friends Ambulance Unit in China from 1946 until the time he had to apply to the communists authorities for an exit permit in mid-1951. There then began a grim journey down the Yangtse under armed guard to Hankow and then by train to Canton, Lowu and Hong Kong. The following extract from the book takes up the story.

(Published by Earnshaw Books, the book is available in Hong Kong, the USA and UK. Enquiries please to me, Andrew Hicks at arhicks56@hotmail.com.)

"In Dominic Faulder’s article published in Bangkok, Jack says that ‘when he was finally released and sent down the river on deck, “three to a mat” with other foreigners, they made him responsible for the group along with Eric Shipton, the famous Himalayan climber and explorer who had been the British Consul in Kunming’. In the full recording of the interview, Jack mentions that he already knew Shipton and had met Shipton’s wife. She’d left Kunming earlier with the children after a similar wait in Chungking for a passage.

In his book Shipton describes the struggle for a cabin on board the steamer and how he ended up sleeping out on deck after releasing his to a Mrs Hemingway who was causing an alarming fuss on finding herself sharing hers with a Chinese man. Early the next morning they entered the Yangtse gorges, the ship ‘the size of a cross-Channel steamer’ racing through the narrow channels between whirlpools and reefs and cliffs like a Himalayan valley. That evening they reached Ichang and were told to disembark. Together with about fifty missionaries they were led off by armed escorts and detained at a squalid and grossly overcrowded inn for sixteen days. The stench from the three latrines was appalling and, fed only with rice and boiled vegetables, they were very concerned about falling sick. They were also worried that if they could not complete their journey in the required month they would be turned back at the Hong Kong border. Even worse, rumours that the communists were going to invade Hong Kong, thus destroying their safe haven, added to the tense atmosphere. Jammed together in these sweaty and insanitary conditions, the discomfort and monotony were extreme. They could even hear the hoots of the steamers on the river, the inn keeper raising false hopes of departure, though they were worried he wanted to keep them there as he was grossly overcharging for their board and lodging.

At last on 4 June they embarked on a boat for Hankow, sleeping in an overcrowded hold with many Chinese passengers and fed from buckets of boiled rice.

‘From Hankow, after a long struggle to get places on a train,’ wrote Shipton, ‘we travelled to Canton, and on the morning of June 1st, the day our permits expired, we reached the Hong Kong frontier.’ Edging in a queue slowly towards the barbed wire barriers, this was the critical moment when they were thoroughly searched and examined. Luckily the examiners were not too hostile that day and at last they were out of communist China and boarding the railway to Kowloon. As Shipton concludes, ‘The hills of the New Territories looked very beautiful in the evening light as, relaxed at last, I watched them glide by the window of the train to Kowloon.’

One further detail is added by Peter Steele, Shipton’s biographer in his book, Everest and Beyond, namely that the boat they took downriver was the Altmark. His account of the journey is in a single paragraph and he says that Shipton arrived in Hong Kong on 1 June 1951 and then stayed in the luxury of the Peninsula Hotel. Suspecting that he had other sources, I wrote to Steele but he told me his account was taken from the autobiography and that he did not remember having anything else. As the Yangtse was within the British sphere of influence with no German vessels on the river, his reference to the Altmark is almost certainly incorrect.

In My House Has Two Doors, Han Suyin mentions that her friend, Dr Mary Mostyn, briefly Jack’s colleague in Chungking, had likewise left China a few months before in January 1951 and been questioned at the Hong Kong immigration point. ‘“Any atrocities?” was the first question she was asked (as were all other missionaries) when they reached Lowu’, the Hong Kong immigration point.

The ultimate terminus for the refugees was the Kowloon railway station where so many romantic journeys into the unknowable vastness of China had for so long begun and ended. The station with its famous clock tower, the only part that remains today, stands on the tip of the Kowloon peninsula, a final finger of the mainland pointing across the water, criss-crossed by ships and junks, to the exuberant capitalist enclave of Hong Kong island. A sight for sore eyes, Jack must have stared in disbelief at its sharp mountain peaks rising from the sea, the lower slopes crowded with buildings, and at the ceaseless vitality of the place, so very different to the unrelieved drabness of a devastated China.

The sense of relief for the exhausted refugees at the border would have been overwhelming, with many scenes of tears and emotional collapse. I can picture the physical setting well as in 1978 I took the same railway line to Guangzhou (Canton), one of the first tourists to be admitted as China at last opened its doors a crack following the Cultural Revolution. On Guangzhou’s five foot ways, teeming humanity in plain white shirts or khaki drab parted to let me pass, staring at me as if an alien with a green face. Despite the greyness I warmed to the energy of the place but even after a short exile, felt relieved as I recrossed to Hong Kong at Lowu, walking the famous covered bridge over the marshes and river that forms the border. This place had been the scene of much Cold War posturing and it looked to be unchanged since the early fifties.

Back on my own side of the bamboo curtain, I saw vibrant colour again, bright clothes and lipstick, the decadent litter of Coke cans on the tracks and for me a palpable sense of home coming. I can hardly imagine how it must have been for Jack arriving as a refugee after so many years of hardship in China.

From these, my researches, I thus concluded that Jack was probably held in Ichang in the same group as Eric Shipton and that he took the train with him to Canton, arriving at the border on 1 June. During some of this time the whole party was indeed ‘imprisoned’, the group herded along together by soldiers, and so the statement in his death notice in the Daily Telegraph was in essence correct."

This chapter of the book then goes on to confirm that my conclusion was indeed correct. Remarkably one of Jack's FAU colleagues in Chungking, now in her early nineties, mailed to me from the USA a letter Jack had written her the day after he arrived in Hong Kong in 1951. This tells in graphic detail all the details of his arrival in Hong Kong and how he was whisked off to the Hong Kong Hotel for a drink, dressed in rags and straw sandals. This letter is a remarkable survival and its discovery one of many extraordinary events that has blessed my research throughout and, I hope, allowed a truly remarkable story to be told.

A TRUE FRIEND TO CHINA