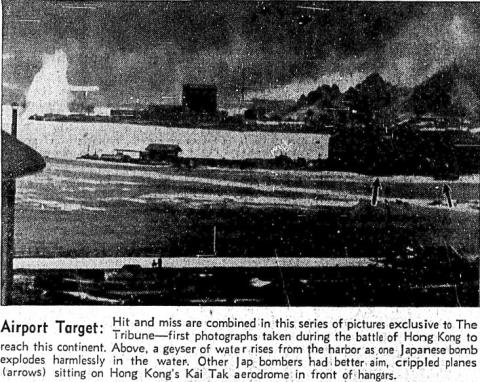

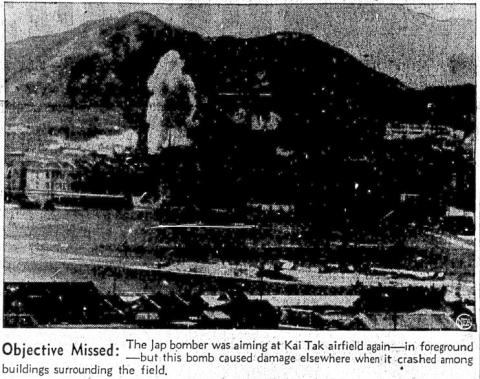

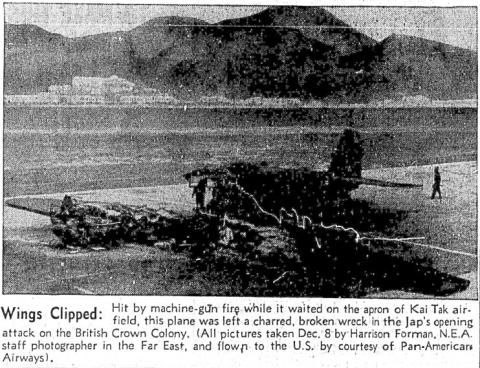

Seventy years ago today, Japanese bombers attacked Kai Tak airfield and the Hong Kong public realised war had arrived. Here are Mabel Redwood's recollections of those days.

I was a young 18 when the Japs attacked Hong Kong, living with my mother and two elder sisters Olive and Barbara in a flat in Gap Road, Happy Valley.

The flats on Gap Road where Mabel lived

I was working as a shorthand typist at Army HQ, though my real ambition was to train as a nurse. My mother had made enquiries about this training two years earlier, but it seemed that no facilities were available in Hong Kong for girls of my age to start this. I had a boyfriend Sid Hale who was the pianist and clarinetist in the Royal Scots Band.

Something's up

Sid and I had gone to lunch at the Dairy Farm shop in Central on Sunday 7th December 1941, and we had just about finished eating when somebody came in, called for silence, and said that any Army or Navy personnel should return to units immediately. Sid went to find a phone; when he came back he said ‘I’ve got to go to Lowu’ – (in the New Territories where the Royal Scots were camping), ‘so must get to Lai Chi Kok where there will be transport.’ I went off with him.

We crossed to Kowloon on the ferry where Sid met up with quite a lot of Army people, but no one seemed to know what was going on – neither did we. We took a bus to Lai Chi Kok , Sid got on some Army transport, and I came back home.

It's war

The following morning Barbs, who worked at ARP HQ [1] very near our flat, was called to the office by messenger at 7.30am, and Mum and Olive and I were having breakfast when we heard planes come over and went and stood on the verandah and saw what looked like planes dropping bombs. We still thought it was a practice!

Bombing Kai Tak

I decided I had better go to work; took my purse and went to the bus stop opposite the Jockey Club where I always caught the bus, and waited. A couple of other people who normally got that bus with me every morning were also waiting including Captain Ebbage who lived in the same block of flats as we did and also worked at Army HQ. No bus came.

Captain Ebbage said he was going to walk to work, so he and I and one other person, set off together, walking right through Wanchai, past all the coffin shops. I can’t remember there being any talk of actual war on the way, but when planes came over we rushed for the first building we could find – inside the Army gate guarded by a sentry.

Captain Ebbage was in uniform, and I had my army pass so we were allowed in and waited in the nearest building. By this time, from the conversations going on around us and the general excitement, we realised this really was an air attack. Also we saw that our shelter was an ammunition store, so shot out as soon as the All Clear sounded.

As I passed the barracks there were all sorts and signs of war activity – troops all over the place waiting for transport. When I got to Army HQ I was told I could not go in. All the big wigs had gone down to Battle HQ [2] and females were not allowed there. We’d known this beforehand – us 4 girls who worked at Army HQ – Peggie Scotcher, Joan Sanh, Virginia Beaumont and me – but no plans had been made for what we should do instead. Here I met Joan and Virginia, and we decided to go to the nearby Colonial Secretary’s Office and offer our services there, which we did, and were given some typing to do.

When it came time to go home, with the bombing that had been going on I was wondering what to do with no buses running, as didn’t fancy walking through Wanchai on my own. Virginia suggested I went to the International Club in Central [3] with her as she lodged there with other unattached females, so I marched off with her, although I had no overnight kit with me and never did get back to our flat.

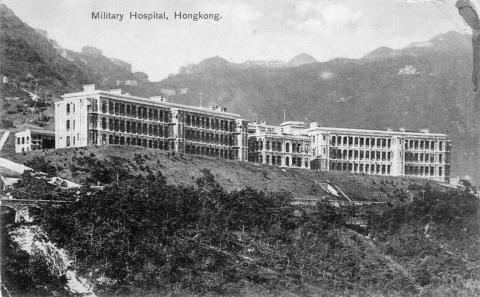

Bowen Road Military Hospital

On the Wednesday morning before I left the Club for the C.S.O. [4], I had a phone call from Mum to tell me Sid had been wounded and was in the Military Hospital Bowen Road. I simply decided I wasn’t going to work, I was just going to see Sid. Off I went, no transport. The previous day I had met Jimmy Bendall, a family friend, and he asked me if I had any money. ‘Not much,’ I said, so he gave me $15, saying ‘You can pay me back later’ – I never did!

I’d never before been to the Bowen Road Hospital, but I knew the Peak Tram Station, so walked up Garden Road to the lower terminus – but no trams seemed to be running. A series of steps went up beside the tram lines, so I ran up these, scrambled across the rails and started along the road to the hospital.

The Japanese were shelling, and it seemed to me that they were concentrating on me! I couldn’t see where the shells were landing; as soon as I heard one crashing, I would run along the road a bit, then hide behind something, then run a bit further; was absolutely petrified until I realised they were shelling very much higher than Bowen Road.

At the hospital I finally located Sid – the only patient in a multi-bedded ward; he must have been one of the very first casualties. I stayed and talked to him all day. He’d got a bullet through his shoulder and was heavily bandaged, though didn’t seem too bad; he was more shocked than anything, and worried because he wasn’t out fighting and all his friends were.

Mabel becomes a nurse

I decided I’d better get back to the Club before it got dark. On the way downstairs I met the Matron, who called ‘Girl, what are you doing? Go and get your uniform on at once!’

‘I’m not one of your nurses,’ I said, ‘but I’d like to be.’

She said ‘We can use every pair of hands we can get,’ so I decided I’d be a nurse right on the spot.

Incidentally, after the evacuation in 1940, one of the stipulations made so I could remain in the colony was that I must join one of the voluntary nursing units, starting by learning First Aid. Well, I did that course, took the exam. and failed, not being the exam. type. I didn’t tell any one at the hospital this!

I walked back to the Club, stayed the night there, then went off with my $15 to try to buy a couple of aprons, but couldn’t find any; then to a chemist to get toothpaste, tooth brush, soap etc. and off I went to Bowen Road Hospital to be a nurse. I didn’t see anything of my mother (who was an Auxiliary Nurse in the wartime hospital in the Jockey Club building in Happy Valley) or of my sisters Olive working with Food Control and Barbs with ARP.

The Bowen Road Military Hospital

We VADs [5] were billeted in a big old house across the road from BMH. We worked from dark in the early morning until dark at night, there was so much to do; I was in my element - a nurse at last!

The most junior VAD, with no training, I was put on the ward with the most injured patients; it was on the ground floor, the only ward that had been gas-protected and completely blacked out. Because these men could not be moved to safety during air raids, there was an extra mattress beneath every bed. During raids, we lifted these and propped them over the patients – the head of the bed kept the mattress off their faces; then we went under the beds. It was terrifying at first, then we realised that the Japs weren’t using very large bombs.

Sid was soon discharged from hospital and went off to rejoin the Royal Scots.

One evening a couple of bombs went through the roof of the 3rd (top) floor but the wards on the two upper floors were empty then, as at night those patients slept beneath the hospital (in space mainly used as a store). This underground part wasn’t very high – you couldn’t stand up there; you bent your head to go along; in some places you had to crouch down, in others you had to go on your hands and knees.

When bombing was particularly heavy late one night, Matron decided to move us nurses then and there from our house into these underground cellars; lying down to sleep, our faces were only about 18 inches beneath the concrete ceiling – not very comfortable. A few days later, we were given better accommodation in a building linked to the hospital by a small bridge, although this had been bombed and was useless.

I remember that fellow Norman Leith (mentioned in ‘The Lasting Honour’): he came into the hospital in such a bad way – he had this gash from ear to ear, I’ve never seen such a wound as that in all my life.

Then there was a young Canadian who came in with worms in his face; he looked about 15 years old, but must have been a bit older than that.

Dear old Mrs Groundwater looked after us VADs, she didn’t work in the wards, but generally mothered us.

Another VAD was Mrs Simon White, whose husband was a colonel in the Army. Apart from uniforms, I had no clothing of my own except what I was wearing when I went to work the day the war started. Nan Grady and I used to share her clothes. A lot of the nurses used to wear slacks when off duty. As I had none, one day Mrs Simon White kindly presented me with a beautiful pair of pale blue slacks. I can’t remember what I wore on top – something else some one gave me no doubt.

I acquired a pair of much-prized scissors from the orderly in the hospital store where I used to be sent to collect dressings etc. He was married and was always showing me pictures of his wife and children. I tied a piece of bandage on my belt and hung the scissors on it. When I was taking temperatures, I would shake the thermometer – and the number of times I hit it against the scissors and broke it... I had to confess to Sister the first few times and was sent to get another; then I reached the stage where I didn’t dare tell Sister I’d broken yet another, but the store man kept me supplied whenever necessary.

One day he gave me a bit of material – the stuff you line curtains with. In the store room there was also a sewing machine which he used to mend sheets etc., so with the material I made myself another pair of slacks. They weren’t very professional – I didn’t have pattern just used my blue ones as a guide. When Mrs Simon White saw the finished product she said I no longer need hers and asked for them back, alas!

In our busy life no one had time for such a luxury as a bath, and there were so many of us nurses that we just tried to give ourselves a lick and a promise, but one afternoon a few days before Christmas I was given time off so decided to take a bath. The water wasn’t very hot but just as I was about to step into it, a VAD called to me saying ‘Mabel, your boy-friend’s back.’

I immediately abandoned the bath, dressed swiftly and rushed along to the casualty ward, and there was poor old Sid again, lying on a stretcher, the tops of two fingers shot off, in an awful mess, blood everywhere. Everything was so chaotic that it didn’t matter at all that I wasn’t a trained casualty nurse – I joined the other nurses in cleaning him up before he was taken to the Operating Theatre. A few days later, he was sent to the convalescent ward opened in the Hong Kong Hotel.

We were now told not to wear our uniforms because the Japs were on the island and there were snipers in the hills around us, and going from one ward to another via the outside verandahs we were vulnerable targets in our white clothes.

The British surrender

On Christmas Day I was preparing a patient to go to the O.T., wearing my ordinary clothes. While he was having his operation, the capitulation was announced; right after, a plane came over and dropped leaflets all around – we went running out and got some of them. Then we were immediately told to put on uniforms again so that when the Japanese came in they would know we were nurses. Thus, when this poor patient came around from his operation, there we girls were, all arrayed in our whites and little cap things. He looked at me and said ‘Have I come to heaven?’ – he thought he had woken up with the angels!

Even after the fighting stopped, there were quite a number of injured people coming in; then things began to ease up a little – just as well, else I think we would all have died from sheer exhaustion. I suppose that was the time when my thyroid problem started bothering me. One day Sid turned up at the hospital to see me – he’d wangled the trip in a lorry, and was about to be sent to Shamshuipo Camp.

The Japanese arrive

Nothing much changed after the surrender except that the Japanese took over one of the offices, and a couple of their soldiers used to clump around with their swords. Japanese soldiers occupied the house opposite the hospital where we had originally been billeted. One night there was such hilarity and noisy singing coming from that house that Matron decided to move us girls to accommodation further from it; so, again in the middle of the night, we were led to a damaged top floor ward. There was a large hole in the roof; although it was covered with tarpaulin, when it rained on the tarpaulin, the water found its way over the edges and on to us. Fortunately a few days later, some repair work was done and the tarpaulin was no longer needed.

I was always happy at BMH. We girls had a wonderful time when we weren’t working (though we enjoyed the work – I did, anyway). I was on a ward with 44 men, whose beds we had to make every morning and they had to be absolutely exact, with hospital corners.. poor patients, they looked as if they were in strait jackets.

I had to wash all the sheets and pyjamas for them, and all the bandages which had to be re-used; first these were soaked in lysol: once I obviously put too much lysol in the water and all my fingers shrivelled, dried, then peeled. I had a few days off work with my hands enveloped in bandages as I got an infection in them.

I discovered a short cut to deal with the bandages – I used to cut out all the nasty parts, wash the rest, and just make rolls of short bandages rolled together. I didn’t think at the time what happened when people came to use the washed bandages and found short lengths instead of one long bandage.

With not much hot water and very little soap, I didn’t do a very good job of washing the sheets and pyjamas: I put them in the bath, took off my shoes and socks and stamped on them – doesn’t sound very hygienic for a hospital, does it? At a later date, some RAMC orderlies formed a laundry to do all this washing. I got on good terms with one of them, he used to wash my uniform for me too, although unis were never ironed.

Major Boxer

I remember Major Boxer was a patient at the hospital.

Major Boxer in 1945

He came to my rescue one day after the surrender - I had been standing on a step at the end of the ground floor building, talking to Bob Bickley, a blind patient, whom I had taken for a walk out in the sun; we were just standing there, he facing outwards and I was facing inwards, so I didn’t see a Japanese soldier coming along behind me – and of course, Bob being blind, didn’t see him either.

Bob had a pair of dark glasses on and was facing where the Japanese soldier was coming. We were both talking and laughing. The soldier came up and grunted at us very angrily – obviously he thought we were laughing at him. Of course we couldn’t answer him, I was just petrified. Major Boxer was sitting nearby, his arm in one of those aeroplane splints, the arm jacked right up high in the air (Very difficult to dress such a patient, one poor man had two.) Boxer spoke fluent Japanese. He called out to me ‘Don’t say anything, don’t say anything!’ (I was too frightened to say anything anyway). He came up to me asking ‘What’s the matter?’ I said I didn’t know, this soldier is shouting at me….. I think he thinks we were laughing at him.’

Boxer straightened the problem out – a very nice fellow. Emily Hahn used to come to visit him, the Japanese would let her in, she used to bring her baby with her in a pram. They lived nearby in Bowen Road, near where my Mum used to work looking after Baby Jean Martin just before the war. I remember going to see Mum there once and seeing the gibbons Emily Hahn kept. I knew Boxer too at Army HQ because he was in the office above me.

Concerts at the hospital

With more time off now, some one started organising concerts. Peggie Scotcher – a gifted dancer herself – decided to teach several of us to do a hula dance which we rehearsed in the bakery. I rather fancied myself in the skirts we made out of sacking which we frayed out, and tops out of scarves. We were very decently clad, and decided to give the dress rehearsal to the patients in the ward who couldn’t be moved so wouldn’t be able to attend the concert itself. Some Japanese officers turned up for the dress rehearsal: they took one look at our hula skirts and said NO to our act.

There were some really good turns at these concerts. An Irish soldier with his leg in plaster sang ‘The Mountains of Morne’, and Bickley the blind fellow had a very nice singing voice. Tamara Jex, Rhexie Stalker and Alison Black (whose doctor Father was killed at St Stephens) and I did a singing act. I wore a borrowed dress and sat on the piano. We sang ‘Ferry Boat Serenade’ which went down so well the audience wanted us to sing more, but we hadn’t rehearsed anything else!

The move to Stanley Camp

About April, I got a bit of a fright when I was called to go to the Japanese Officer’s office. Major Boxer appeared again because he was used as an interpreter. The Japs wanted all sorts of details about me: it was a mystery to me, I didn’t know whether I was going to be beheaded or what.

It was some months later that I was told to see Shackleton, the big boss at the hospital, with 3 other VADs. A Japanese was present. Shackleton told us we were going to be sent to Stanley that very day. Then I learned that Mum had been asking the Japs to have me brought into the camp - that earlier interview with the Jap officer had been because they had decided to have a look at me first. We 4 were told to go and collect our things right away. I didn’t want to go at all! I was extremely annoyed, as I was having the time of my life at the hospital.

Later that day a lorry appeared and we were put on the back of it, an open lorry. I didn't have many bits and pieces. I purloined a sheet I brought into camp where we Redwoods divided it into four so each had a little piece to put across our tummies.

The lorry went along Bowen Road and down Garden Road to the HK & Shanghai Bank, and there we sat in the back for about an hour, not allowed to get off. It was hot then – June. After a while the Japs told us to go inside the bank, and there we met a whole lot of other British, some were nurses from St Teresa’s Hospital in Kowloon.

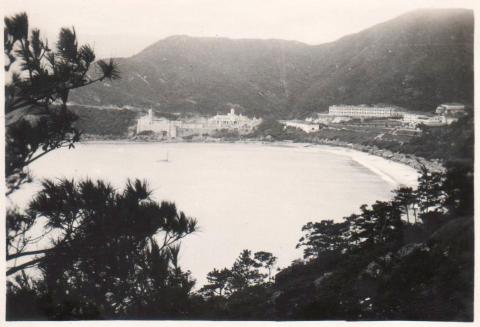

HK & Shanghai Bank (large, white building on left of photo)

It was lovely and cool in the bank, with the air-conditioning so pleasant after sitting out in the boiling sun with no hats or anything. We all finally got on the lorry and came via Deep Water Bay .. I remember we went all round the road we took when we used to go to Repulse Bay, to Jimmy Bendall’s matshed.

1930s view of Repulse Bay, with matsheds along the beach

Passing the matsheds down on the beach, I thought about all our swim suits we had left there; and how when we came home from swimming we used to drive via Aberdeen and call in at the Dairy Farm cafe and have milk shakes and ice cream sundaes.. we went that way in this lorry, and I remember looking at all these places and wondering if we would ever live that sort of life again.

When the lorry came into camp, I saw my sisters first, then Mum but I barely recognised her because she had lost about 60 lbs. in weight through malnutrition and a hysterectomy 2 months earlier; and there I was, back with my family again – and rather bad-tempered I think, especially when I found that initially my bed was actually suitcases on top of each other!

This text was originally posted to the Stanley Internment Camp discussion group by Barbara, Mabel's older sister. Barbara now lives in England, while Mabel lives in Australia. Many thanks to Barbara and Mabel for their kind permission to re-publish the text on Gwulo.com.

Notes:

- 'ARP HQ' was the headquarters for group responsible for Air Raid Protection. More information...

- The 'Battle HQ' was also known as The Battle Box, an underground headquarters built on the old Victoria Barracks site. More information...

- Can anyone confirm the location of the Women's International Club? Barbara believes it may have been in the Gloucester Building.

- The C.S.O. was the Colonial Secretary's Office on Lower Albert Road. More information...

- 'VADs' stands for Voluntary Aid Detachments, which were formed to provide volunteer first-aid and nursing services. Over time, 'VADs' was also used to describe the volunteers themselves. More information...

- You can click any of the photographs in the article to see a larger copy. The photos of the Gap Road Flats and Major Boxer are hosted on the UWM and Google websites respectively. You can click the photos to visit those websites.

- For more resources about Hong Kong in WW2, click here.

Comments

Hong Kong at war

As an ex military nurse and amateur military historian, and very interested in HK history I found this article fascinating. How everyone everyone coped is almost unimaginable!

Thanks for sharing this

re: Hong Kong at War

I'm glad you enjoyed Mabel's story. You might also enjoy Barbara's diary, which covers the same time in Hong Kong.

Barbara is Mabel's older sister, and we're serialising her diary as part of the '70 years ago' project.

Regards, David

Diary

I read all the sections and had an extra long lunch break - she makes it sound 'normal' when it must have been terrifying.

Barb

It is a remarkable

It is a remarkable recollection of those horrible days when gallant men and women took up the defence of Hong Kong. Hats off and salute !