Sex

Male

Status

Deceased

James Legge graduated from Aberdeen University in 1836 and joined the London Missionary Society two years after. He was sent to Malacca in 1840 where he assumed the post of principal of the Anglo-Chinese college founded by Robert Morrison. When the school moved to Hong Kong in1843, Legge remained as Principal. He was a great Sinologue and was famous for his translation and annotation of the Chinese classics. He was a prominent resident of Hong Kong as he was an all round man: Scholar, missionary, minister, chaplain and Educationist. He was often consulted by the government on matters relating to the local Chinese community.

Interactions of East and West: Development of Public Education in Early Hong Kong, Nixia Wu Lun p24

Comments

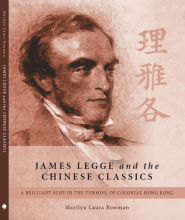

my new book; James Legge and the Chinese Classics (2016)

I have just published a biography of James Legge (1815-1897), the brilliant Scot who was the first to translate all the Chinese Classics into any European language when struggles between Britain and China included two wars.

He was a great scholar and missionary in Hong Kong when struggles between Britain and China included two wars. It was an era of sailing ships, pirates, opium wars, the swashbuckling East India Company, cannibals eating missionaries, and the opening of Qing China to trade and ideas. Legge was vilified by fundamentalist missionaries who disagreed with his favourable views about Chinese culture and beliefs. He risked beheading twice while helping Chinese individuals being terrorized during the Taiping Rebellion. He became so ill from Hong Kong fevers when only 29 that he was forced to return to the UK to save his life. Recovering, he and his three talented Chinese students attracted such interest that they were invited to a private meeting with Queen Victoria. Legge thrived despite serious illnesses, lost five of his 11 children and both wives to premature deaths, survived cholera epidemics, typhoons, and massive fires. He was poisoned twice in a famous scandal, helped save a sailing ship from fire on the high seas, took in a bohemian Qing scholar on the run, foiled a bank-bombing plot, and earned enmity in the colony for providing court testimony about translation that favoured accused Chinese men rather than the colonial authorities. Legge’s resilient responses and incredible productivity reflected the passion he had developed at the age of 23 for understanding the culture of China. He retired to become a Fellow of Corpus Christi College and the first Professor of Chinese.

James Legge

The following outline of James Legge's life was given as a speech by L T Ride at the Union Church on 20th December 1965, marking 150 years since James Legge's birth.

JAMES LEGGE – 150 YEARS.

To those of us who knew Hong Kong pre-war, it is amazing to see how post-war Hong Kong has been “discovered” by the rest of the world, and how it has attained, in the opinions of most of its ever increasing number of visitors, the status of a tourist Mecca of the Far East, or in their modern terminology, a “must”; but there are still many aspects of life in this Colony which should keep us from becoming house-proud, and in any case, why should we, mere sojourners in geological time, take any credit for the beauty that Nature has provided, or for the shoppers’ paradise which surely may well be but an artefact of transient economic trends?

But peculiarly enough, historians too are beginning to proclaim Hong Kong’s gallery of great men and at first sight it would seem, for her size, she has been associated with more than her fair share of men of international fame; in this connection the names of Sun Yat Sen, Morrison, Legge, Chinnery and Manson come to mind, and be it noted, each of these – with the exception of Chinnery – was either directly or indirectly associated with some aspect of the work of the London Missionary Society.

In none of these cases however was Hong Kong directly responsible for the international spot-light; what Hong Kong did was to provide the opportunity which each worker readily seized, and of this, the life of JAMES LEGGE is an excellent example.

Legge was born at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, exactly one hundred and fifty years ago today; his parents were staunch Independents and he was first taught to read by a blind woman using as a lesson book the metrical version of the Psalms, which she knew off by heart. His primary education he received at the Huntly Parish School and he commenced his secondary education in 1829 at the Aberdeen Grammar School. For what we now call higher or University education, he went to King’s college, a XVth century foundation which in 1860 was reconstituted along with Marischal College to form the University of Aberdeen, as we know it today.

It was at King’s College entrance examinations that Legge won his first academic laurels, which heralded in a brilliant undergraduate course, crowned later by a degree, coveted prizes and an offer of a post on the staff which would eventually lead to a chair; but one of the qualifications in those days for appointment to a Chair at King’s College was membership of the Established Church of Scotland. This qualification Legge did not possess, nor would his conscience allow him to acquire it; this he could very easily have done, but many years previously his father had left the Presbyterian Church out of sympathy for the treatment meted out to one of its more progressive ministers, the Revd Cowie. Legge senior agreed with Cowie’s modern views on lay preachers, foreign missions and other matters of controversial church policy, and when Cowie was dismissed from the Presbyterian Church because of these views, Legge also left and joined the Independent Church. Young James Legge’s comment on his professor’s offer was: “I thought it would be a bad way of beginning life if I were, without any convictions on the subject, to turn from the principles of my father merely because of the temporal advantages which such a step would bring me”. Even at that early stage of his career, Legge’s method was example, not precept. It is doubtful therefore whether it was a disappointed Legge that left his University where such a brilliant future of promise was opening up before him, to accept a lowly teaching post in a school at Blackburn; more likely was it a Legge completely happy in having had the strength to do what he felt was right, even at the cost of a professorship. At any rate his new post gave him ample time and cause to think of what he was to do with his life, and it was during this period that he felt the call of the Church. In 1837 he was accepted at Highbury Theological College and while there he made the further decision to work in missions abroad; in 1838 he offered his services to the London Missionary Society.

Strangely enough, after all these weighty decisions had been made, instead of life becoming easier for him it became more difficult in a number of unsuspected and petty ways. First, one of the members of the Selection Committee unfortunately wrongly interpreted a statement in a letter from one of Legge’s sponsors to the effect that he was specially suited for work in the East, as an attempt to dictate to the Committee where he should be posted. This misunderstanding being cleared up, he was next faced with a problem over the medical report from one doctor who feared that he might turn out to be susceptible to consumption, and recommending him for the Cape or the South Seas, but not India, which negation applied also to Further India. Legge queried this and the medical opinion was later modified by retracting the objection to Canton because frequent changes to Macao were possible! Insalubrious Hong Kong was not yet on the world map! Then came one more question: “Are you married, and if not, are you under any engagement relating to marriage? Or have you made proposals of marriage to any one, or are you willing to go out unmarried should circumstances render it desirable?” To this verbose and somewhat muddled question from the examiner, the scholar’s concise reply and even more concise counter-question was: “I am not married, neither am I engaged, and should circumstances render it desirable, I am willing to go out unmarried. But who is to be the judge of these circumstances?” Then Legge, the human young man of 23, perhaps blushingly, perhaps confidingly, added: “The latter part of the query has frequently engaged my thoughts, but as I would neither do or say anything rashly, I decline answering it in the meantime”.

The Committee had to wait six months for the answer, for not until 3 December 1838 was Legge able to write saying that he had become engaged to the Revd John Morrison’s only daughter, “who is in no way disqualified to be the partner of a Missionary”.

The Committee agreed with Legge; he was married early in 1839 and he and his wife sailed for South China in July of the same year, but the political situation here at that time was such that it was deemed advisable that they should be diverted to Malacca; so Legge and his wife disembarked at Anjer, went overland to Batavia, took ship thence to Singapore where they transshipped to Malacca, arriving there on 10 January 1840.

Malacca was then the headquarters of the London Missionary Society’s Ultra-Ganges Mission, so called because at that time little was know by people in Europe about places the other side (to them) of India, and this whole area was referred to as, rather than named, “Beyond the Ganges” or “Ultra-Ganges”.

The ultimate objective of this mission post was of course China, but that vast land, supporting even then three hundred million souls, was not ready to admit foreign missionaries – there were of course Jesuits in Peking, but they had special permission – nor would the Portuguese authorities allow proselytizing Protestants to remain in Macao – Morrison being the one exception, because he was on the East India Company staff, and was not engaged in evangelical work. Morrison was not sent to China as an evangelist, but to learn the language, to prepare text books, a grammar, a dictionary and tracts that others might learn the language more easily, and to translate the Bible into Chinese that the people might be enabled to read the Scriptures for themselves. Morrison had to plan so that his instructions and the Mission’s ultimate aims could be dove-tailed together, and his decision was that a mission should be set up in a Chinese community where China itself had no political jurisdiction, and there to found an Anglo-Chinese College where the East could be introduced to the West, and the West to the East without outside interference. The students did not have to become Christians to enter the college, for “Intense as were his (Morrison’s) Christian convictions, he could sanction nothing that would do deliberate violence to the convictions of others”; but of course it was hoped that some of the students would eventually undertake the evangelizing work in their motherland, a task denied to the missionaries.

The opportunity to put his plan into action came with the arrival of the Revd William Milne who was sent out by the Mission to China to join Morrison. When permission for him to stay in Canton or Macao was refused, Morrison sent him on what today would be called a fact-finding mission – to the East Indies and Malaya – and on his return, he and Morrison agreed that Malacca should be the place for the Mission, its College and its Press.

Milne went to Malacca to put these plans into operation; he became the first Principal of the College, and Morrison its first President; a press was established and in a few years the Mission had earned a reputation for its “thoroughly sound, quiet and efficient work”.

But in 1822 Milne died, and in 1834 Morrison too was called to his rest, and the Malacca mission fell on difficult times, and so too did the work in China in the years when the clouds of the first Sino-British war rose above South China’s horizon.

These were the conditions prevailing beyond the Ganges when Legge began his work in Malacca. He at once took over the Principalship of the College and charge of the press, as well as taking his full share of preaching and teaching as soon as his spoken Chinese was adequate; but he altered nothing of Morrison’s and Milne’s work until he had tested and tried it himself, with the result that after a couple of years’ actual experience, study and trial, he was convinced Morrison’s plans were wise; he accepted them as his own, and pressed on with them with all the vigour of the newly arrived and all the revitalizing that comes with fresh blood; in addition he did not refrain from breaking new ground when experience led him to believe it expedient and essential.

Their common aim was to bring Christianity within the grasp of all Chinese, and they both believed this could be done best only by the combined efforts of Chinese and Europeans. In the vineyard of Christ there was no place for national differences between the labourers; Cornelius, as we heard proclaimed by Chinese lips tonight, was astounded when Peter told him that in Christianity there was no place for any distinction between Jew and Gentile, and both Legge and Morrison had learned that if China was to become Christian, Peter’s admonition to Cornelius must apply, excepting that for “Jew” we must read “Chinese” and for “Gentile” we must substitute “Barbarian”. Morrison and Legge both realized that each national had his own specific part to play, and that to attain their aims would need the combined efforts of both Chinese and foreigners; teaching the people and preaching to them could best be done by the Chinese themselves, and as Legge saw it, his task was to train the Chinese to be teachers and evangelists in theology and Biblical science, and to train foreigners to serve by promoting any organizations, be they schools or hospitals which give them the opportunity to demonstrate to the Chinese the Christian way of life.

There were however two main spheres in which Legge applied his energies slightly differently – though in the same direction – from Morrison. The first was in the location of the Mission, and the second was in his own Chinese studies.

After the first Sino-British war, the whole international situation in South China was altered; a small barren island off the China coast and the tip of the neighbouring peninsula of Kowloon had become a British Colony, and five treaty ports in China itself had been opened to foreign trade. To Legge it seemed, and he was able to persuade the Society in London to agree, that now was the time to move the Mission to China, and he wrote to this effect to J.R. Morrison – the son of the late Dr. Morrison – who at that time was the British translator and interpreter at the treaty negotiations being held in Nanking; when John Morrison received Legge’s letter on 11 September 1842, he immediately answered: “Your scheme for the removal to Nanking or rather Peking is, my dear friend, too imaginative. No, we must establish ourselves in British ground, and Hong Kong as I have said before, is the place. Make up your mind then, to Hong Kong; hasten my dear Legge, to make your arrangements for settling there …”.

Legge did, for he was shrewd enough to recognize that this advice came from the wise son of a wise father, and on 6 July 1843, the Revd James Legge, his wife and children, arrived in Hong Kong. Legge’s apprenticeship was over; in Hong Kong his life’s work began in earnest.

The second difference between him and Morrison was the scope of their Chinese studies; Morrison’s was basic – a grammar, a dictionary (Chinese-English, English-Chinese), a Bible in Chinese; all these were essential tools for the foreign missionary taking up work in China; Legge took the next step, and logical though it was, it took a courageous and determined man to undertake it. He realized that while we had much to teach the Chinese, we also had much to learn from them; the Chinese already had a philosophy which had stood the test of many centuries of their time; would not our teachers have a greater chance of persuading them to accept another philosophy, if first of all such teachers knew something of the philosophy of their students? Legge’s self-imposed task was to translate the Chinese Classics into English and thus open this store of Chinese knowledge to the foreigner. This he accomplished in thirty years, in addition – be it noted – to all his other labours, none of which did he shirk.

As a missionary, Legge knew where his first duty lay, but he knew that he had other obligations as well, for example to his own brother Christians. This is the crux of the whole of this talk to you this evening, and it is the reason why all of us are here tonight; it is the reason why this Church is here, for his thought, expressed in his own words, - which I shall now read – led to the foundation of this Union Church.

According to Legge the “first beginnings” of the Union Church were in his house during 1843 where a few people used to meet “more as a Bible-class than an assembly for public worship”. He described it as follows:

“… After residing here for about twelve months, various circumstances forced upon my mind the desirableness of there being a place of worship in the island in which Protestants of all denominations and of different countries might unite and observe the Ordinances of Christianity, without reference to minor differences in points of doctrine and Church order. I talked the matter over with my colleagues, Dr. Hobson and the Rev. Wm. Gillespie, and the result was, that on the 19th August 1844, we issued a circular requesting ‘the assistance of the foreign community towards the erection of a Chapel for public worship in the English and Chinese languages, in connexion with the London Missionary Society’. We stated that ‘the services in the proposed chapel would be conducted in conformity with the fundamental principle of the London Missionary Society, with a view neither to advocate nor to apologize for the peculiar tenets of any party, but to expound and enforce those great doctrines which are held by Protestant Churches in common’, and that ‘the Ordinances of Christianity would be administered without distinction of denominations’. …”

As a result of this circular enough money was collected to buy a plot of land in Hollywood Road and erect there the first Union chapel, and of this sum more than one third was subscribed either by or through the London Missionary Society, from outside the Colony.

“Such were the conditions”, continued Legge, “under which the Union Chapel came into existence. It was to be for public worship in the English and Chinese languages in connection with the London Missionary Society; it was to be the Sabbath home of a really Union Church and congregation. Should the London Missionary Society be unable, in course of time, to conduct public worship in it by means of its agents, it was to be, in such a case, in the hands of Trustees, to deal with it on behalf of the Protestant Foreign community, as that community should be pleased to direct”.

I do not intend this talk to develop into a detailed history of this Church, interesting and important though that may be, but I must dwell for a few moments on another aspect of it and that is, its name. In these days we hear so much of the Union of Churches, and see so little accomplished in that direction, that one begins to despair of people ever learning to differentiate between union and unification. While people are made differently, have different experiences and opportunities, they will always think differently. Legge knew this 120 years ago, but he also knew the answer. He first set up his Union Church, convinced everybody that it would work, and then thought of the few essential rules afterwards. That was in 1844 or 45, and for the first few years of its existence, there was no officially recognized Pastor of the Union Church, nor were there any rules; the care of the Church was a part of the work of the London Mission and two of their members conducted the services. But by 1847 the congregation had grown so much that it was felt they could support a Minister of their own. After two years of fruitless efforts to recruit a pastor, they finally decided to ask Dr Legge to undertake the duties officially. On the 12th May 1849 he accepted and one of the first things he did was to persuade the Church to draw up a “Declaration of Faith and Order”. This was done by a committee of which Legge was the Chairman, and it was accepted by the Church members on the 27th July of that year.

The first three paragraphs of this declaration are so important that I feel you should hear them. They read:

“We, whose names are attached to the following declarations, desire at the outset to express the simple object for which they have been drawn up, namely, that we might have a document which should express the principles on which we are united in fellowship as a Church of Christ. Such a document we have thought would enable us better to understand one another, and might be shewn with advantage to enquiring Christian friends.

There are two principles, which we all recognize; the one is, our duty to confess Jesus Christ and to do what we can to win men to the faith of the Gospel; the other is, our duty not to forsake the assembling of ourselves together, but by a union with Christian Brethren, to maintain the Ordinances of Divine Worship, and proclaim to the world our attachment to the truth as it is in Jesus. Holding these two principles we find ourselves in the Colony from different countries, and from different Churches. It is a consequence of this, that we do not entertain the same views on many points of Church Order and Government, and that we have not looked at all points of doctrine exactly in the same way. Ought we on this account to have remained separate from one another, avoiding a public and determinate fellowship? To have done so would, we believe, have been wrong. We differ in small matters, we agree in great realities. We trust that we are one in Christ Jesus. We all love Him who died for us. We all acknowledge our obligations, as naming the name of Christ, to depart from iniquity. On the fact of this great unity, our Union as a Church is based. Believing that we have been individually received by Christ, we joyfully receive one another, and pray that our doing so may be to the glory of God, while at the same time, we express our resolution in dependence on Divine Grace, whereto we have already attained, to walk by the same rule, and to mind the same thing.

The above is the fundamental principle of our Union”

Had Legge achieved no more than that, he had earned fame in the annals of the Church, but he also played a pioneering part in Education in the Colony, not only in the mission schools but in Government schools as well. His own college he amalgamated with the school of the Morrison Education Society, but while he was away in England this fell on evil days. He however had them resurrected in another form later and in the Colony today they still flourish. He was instrumental in having a committee set up to advise Government on primary education in both English and in the vernacular, and the inception of the Colony’s Department of Education was a direct result of his wisdom and drive. At the same time he was by no means immune to the trials and tribulations of ordinary men. He had lost two sons in Malacca, and in the cemetery in Happy Valley here he laid to rest a daughter and his wife. In the sixties he began to feel the strain of climate and work, and in 1867 he tendered his resignation to both the Union Church and to the London Missionary Society. He had already received the thanks and an acknowledgement in the form of a Salver, tea and coffee service from Government “for many valuable Public Services readily and gratuitously rendered”. The Church found it more difficult to express their feelings at his departure. He had seen the congregation expand and outgrow the old Chapel in Hollywood Road; he had seen a new Church built and opened in Staunton Street on 16th April 1865, and it was no wonder that at the Annual Meeting on 21st February 1867, he was referred to as “the founder and the father of the Church whose care, endurance, sound doctrine and kindly sympathy had always characterized his labours with them”.

His return to his native land resulted in a most welcome restoration to his former health and vigour and enabled him to push ahead with the yet unfinished portion of his work on the Chinese Classics, and by the end of 1869 it was ready for publication and he returned to Hong Kong to supervise its printing. He arrived back here in March 1870 to find that the pastor of the Union Church had only two months previously resigned and left the Colony. The pastorate was naturally offered to Legge and just as naturally he accepted and so in April 1870 began his second pastorate which has been described as “as happy and prosperous as his first”. His congregation frequently numbered over 200 and it was during this incumbency that the Sunday School was first formed and the Church began to help needy causes outside the Colony. It is of interest to us to hear that in addition to contributing to the fund in aid of the sick and wounded in the Franco-Prussian war, the Church also responded to the plea for help from the Lancashire Cotton Famine Fund!

In 1873 Legge left Hong Kong again on retirement for his native land, via North China, Japan and the States. Of this inevitable move he wrote: “I have done my work in my day and generation; not that I will then surrender myself to idleness; but whatever I do need only be done on the impulse of my own”. That is what he wrote in Hong Kong when retirement was ahead, but what he actually met in England, was a stage very differently set. He arrived there to find that in academic circles he had won international fame and that he was acclaimed as a Sinologue worthy of the highest academic honours. Funds were made available for the University of Oxford to establish a chair in Chinese to which he was appointed but again, as had happened forty years before, there was a slight impediment, but fortunately this time, not involving his conscience, but that of the University – if a University can be accused of having such a thing. At that time, no one could be appointed to a Chair at Oxford unless he was a graduate of either Oxford or Cambridge. Legge was neither, but where a man of his attainments and standing was concerned, the Vice-Chancellor was able to rectify that. In 1876 Legge embarked on another life’s work; he became the first Professor of Chinese at Oxford and the first non-conformist to be appointed to a Chair. This Chair he occupied for 21 years until his death on the 29th November 1897. His days in Oxford were as happy as they were fruitful, but neither his success nor his happiness there could efface his memories of Hong Kong.

Legge was buried in a cemetery just north of Oxford where his grave is marked by a polished Aberdeen granite headstone, the inscription on which modestly refers to him as a “Missionary to China and first Professor of Chinese in the University of Oxford”.

On the day of his burial, a memorial service was conducted in the Mansfield College chapel, and in the address made by the Revd A.M. Fairbairn, occurs this passage:

“James Legge had a rare largeness and simplicity of nature, and was distinguished by the dignity which never fails to adorn the single-minded man. He was, though so upright, as gentle as a child and while severely conscientious he was saved by his delightful humour from being either fierce or fanatical. Oxford did not know him till the shadows of his long and gracious evening were beginning to fall, but it saw him soon enough to know that he was a man of fine presence, pure purpose, and courageous speech; a man whose high spirit a small school and imperfect sympathy could not break, whose wide and lofty aims a circumscribed sphere could neither narrow or lower. … He was sent Eastwards, to the oldest of living civilizations, and he studied it with an eye made luminous by love. For if ever man loved a people, James Legge loved the Chinese, and he could not bear to see them do wrong or suffer it. …”

In 1928, thirty years after his death, a deputation of professors from an international conference placed a wreath on his grave with the following memorial attached:

To the immortal genius of the great master,

James Legge, from the sinologists assembled at

the 17th Congress of Orientalists at Oxford,

August 31st, 1928.

To the members of this Church, our Legge memorial – the wording of which you will find in the notice of this service – is now more than a memorial to Legge; through its own varying fortunes it has become a reminder of the varying fortunes of its Church and yes, of those of life too, but it is also an assurance that by faith these may be overcome. It was erected by general subscription in 1898 in the first Union Church on this Kennedy Road site. This stood from 1891 until destroyed by a bomb during the hostilities in 1941. The Legge and Chalmers memorials (a third has, I understand, recently been found) and the foundation stone of the building were fortunately saved from destruction and were given rightful places of prominence in the present building, so that when leaving this Church, one cannot but help notice the Legge memorial and be reminded of how much the world of scholarship, the Colony and this Church – in fact the whole Church of Christ throughout the world – owe to the example and the life of this great man.

Could this stone compose its own message it would probably read: “If you have any doubts about the desirability or feasibility of Church union, look around you”.

Legge’s work still lives in the world of learning in his writings, in this Colony in his achievements in education and social service, and in this Church which is the resurrection of the one in which he led the way to Union.

Union Church ===> ?????

Union Church ===> ????? Church in Chinese writing?

1872 Recollections of Rev. James Legge

Rev. James Legge arrived in Hong Kong in 1843. He delivered an interesting lecture of his recollections of Hong Kong at the City Hall on 5 November 1872.

Please see the November 1872 China Review at: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/tq57v092s#?c=&m=&s=&cv=22&xywh=-443%2C610%2C3158%2C1498